If you’ve ever wanted to explore the world of “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings,” the best place to start might be Oshkosh.

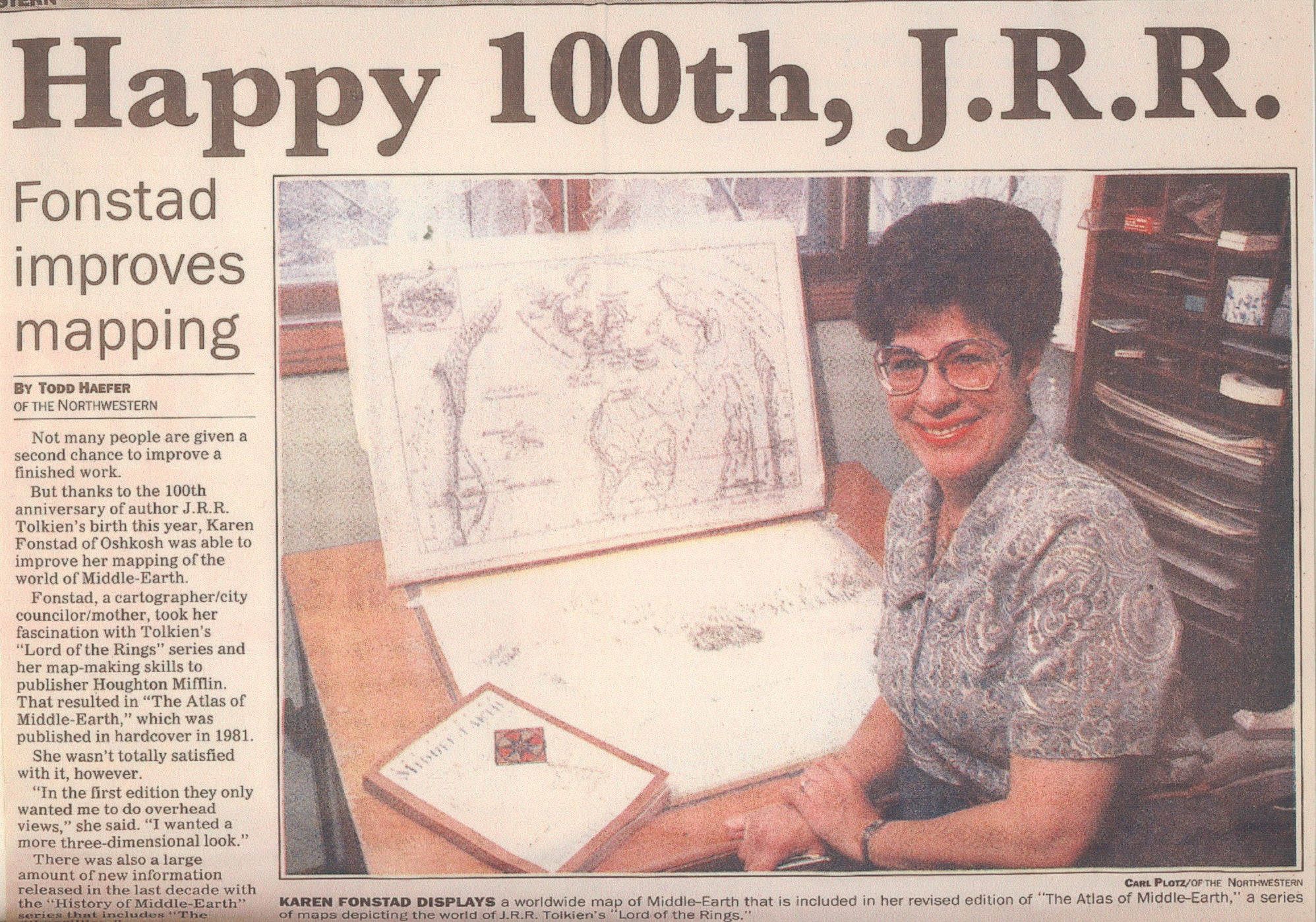

That’s where a Wisconsin cartographer created dozens of maps that went into “The Atlas of Middle-earth,” the official geographic guide to the world of author J.R.R. Tolkien. Her work went on to influence “The Lord of the Rings” movie trilogy.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Like many readers, Karen Wynn Fonstad fell in love with the fantasy series and went through multiple readings. Unlike most readers, she was trained as a cartographer, and came up with an ambitious plan to use the texts to create realistic maps from Tolkien’s texts.

Fonstad passed away 20 years ago. Now, her husband and her son — both geographers themselves — have embarked on a new quest: to digitize her original maps and find an archive to house them.

Rob Ferrett and Beatrice Lawrence of WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” secured an invite to see this process firsthand.

Preserving a legacy

Mark Fonstad grew up with his mom’s maps of Middle-earth and other fantasy settings.

Todd Fonstad, Karen’s husband, has been storing those maps for decades at his home in Amherst.

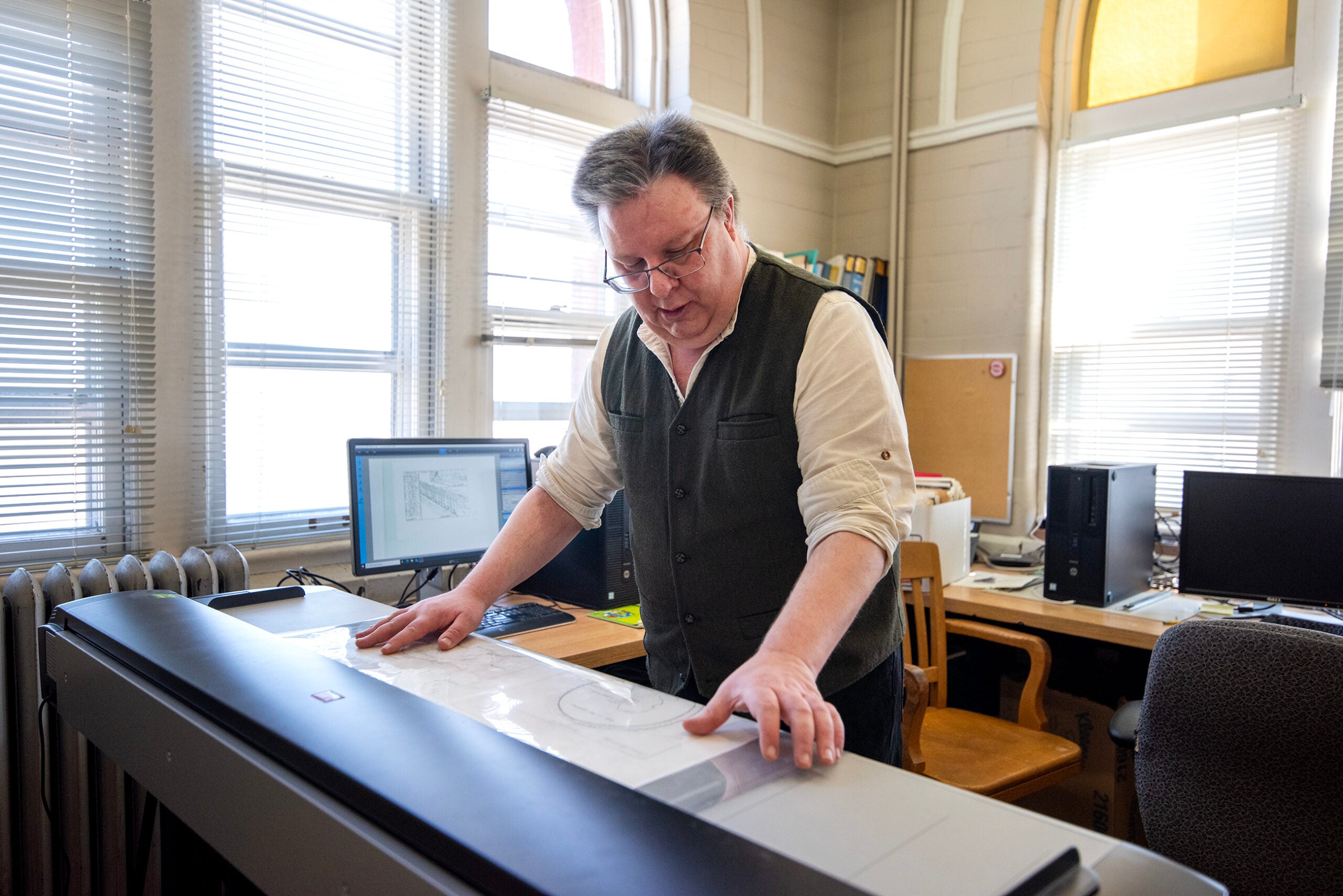

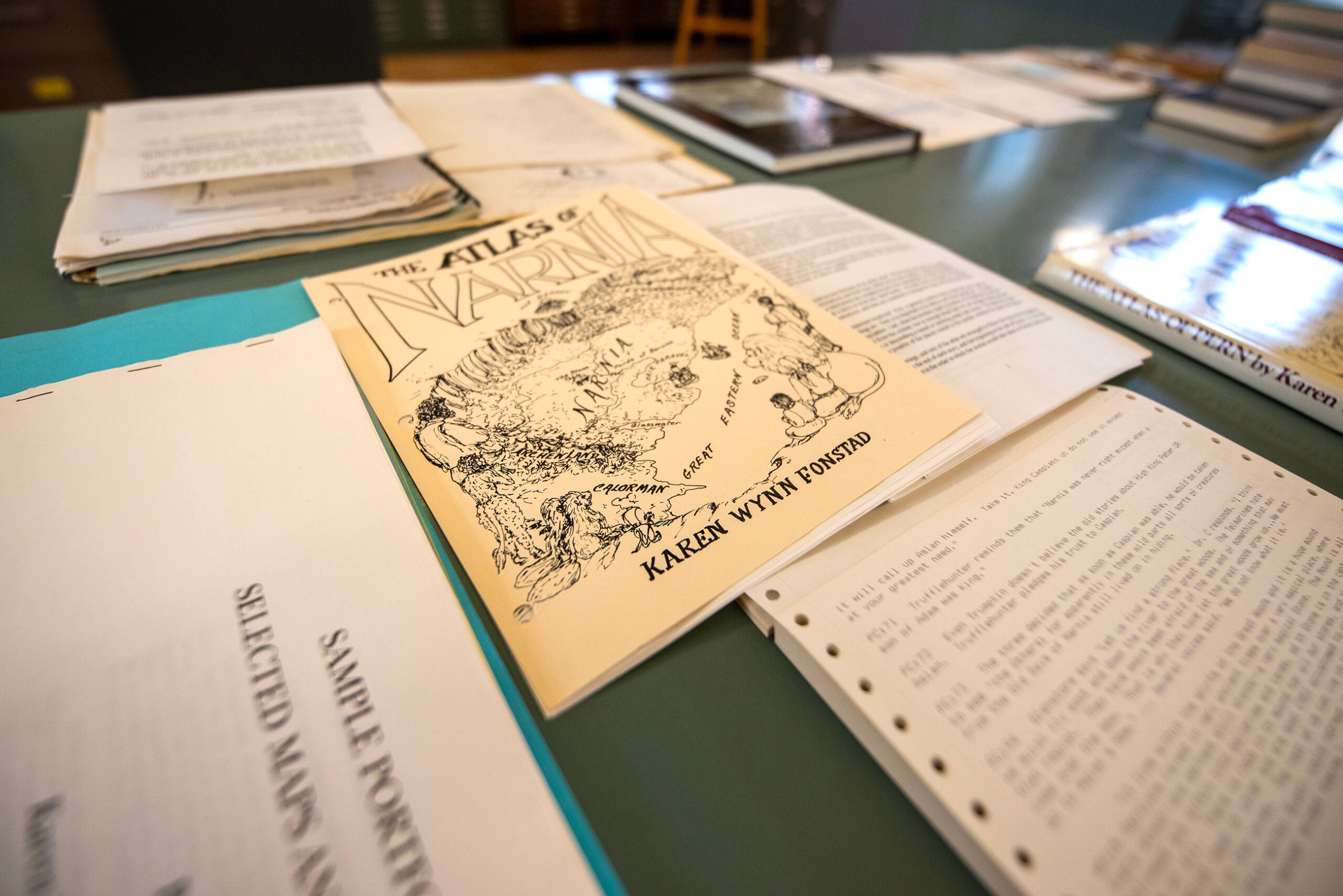

Mark is now an associate professor of geography at the University of Oregon. He spent spring break this year in Wisconsin, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Robinson Map Library. For a week, he covered the library in fantasy maps as he worked to scan and digitize the collection.

It’s a tall order.

“It’s a little bit of an overwhelming process because, first of all, there’s hundreds of maps. Secondly, the maps are built in such a way that they have many layers to them,” Mark said. “I barely scratched the surface this week.”

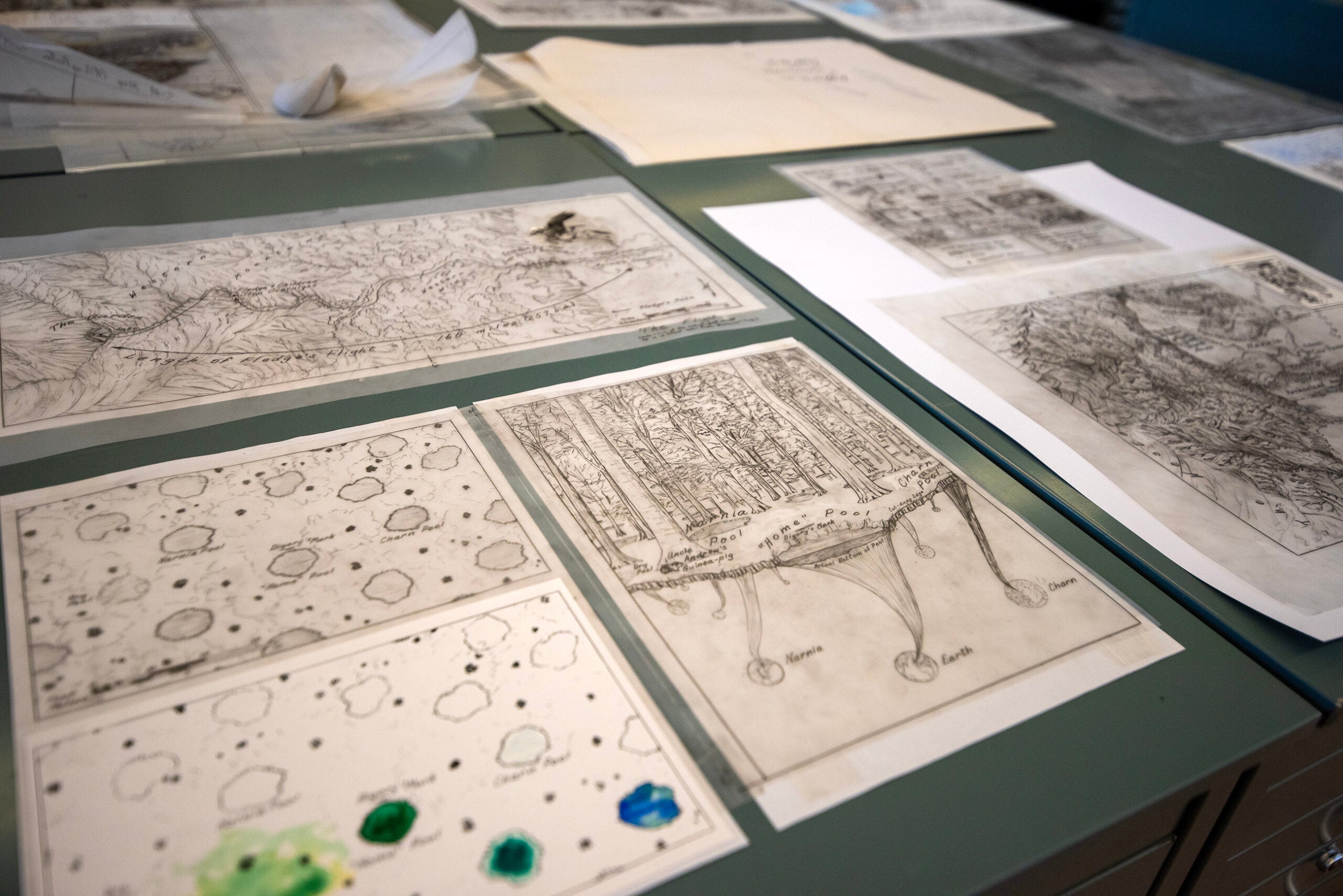

As we walk into the map library, we are surrounded by Middle-earth. Mordor, the Shire and all points in between are represented. And not just Middle-earth. Karen created works for other fantasy worlds — some never published.

How do you scan a collection of maps of varying sizes, some of them in delicate condition?

You need a big scanner, caution and some patience.

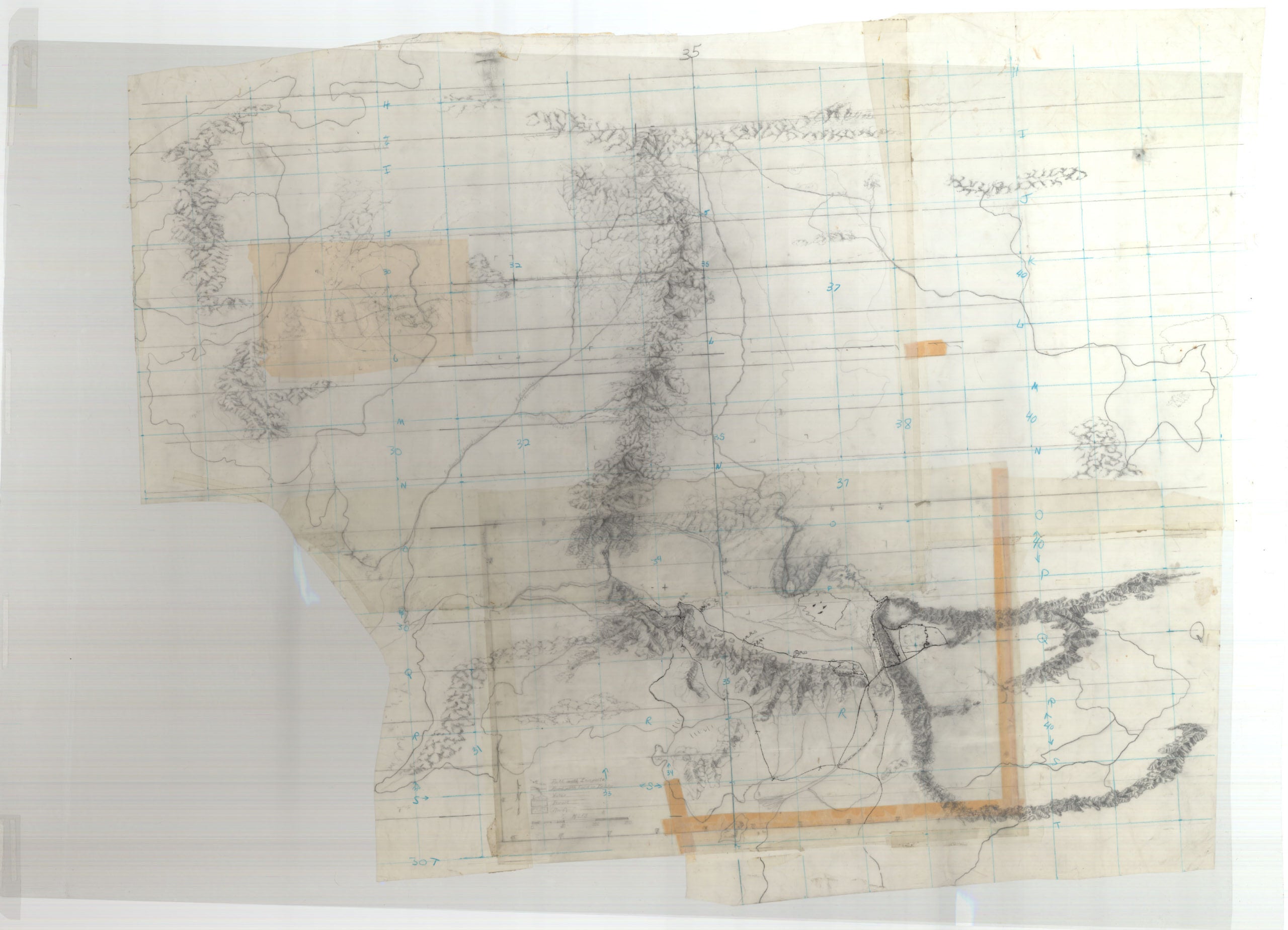

One of the biggest challenges was the base map of Middle-earth, which Karen used as her foundation for the other maps. It’s large — big enough for a 6-year-old Mark to lay on when spread out on their kitchen floor.

Because Karen made heavy use of it during her work on the atlas, Mark said it was in the “absolute worst condition” of the collection.

But Mark said the payoff will be worth it if the digitized copies help the collection find a home in an archive, along with a digital catalogue. And he said technology is developing that could share the maps in a new way.

“My preferred way to see these maps, besides having them out on the tables and actually looking at them, would actually be to have them in a [virtual reality] room — to have VR goggles and actually be able to look at them in the way that they were intended,” Mark said.

The Atlas of Middle-earth

Karen was born in Oklahoma. She attended the University of Oklahoma, where she got her master’s degree in geography and met Todd. After they married in 1970, they moved to Oshkosh, where Todd got a job as a professor of geography at UW-Oshkosh.

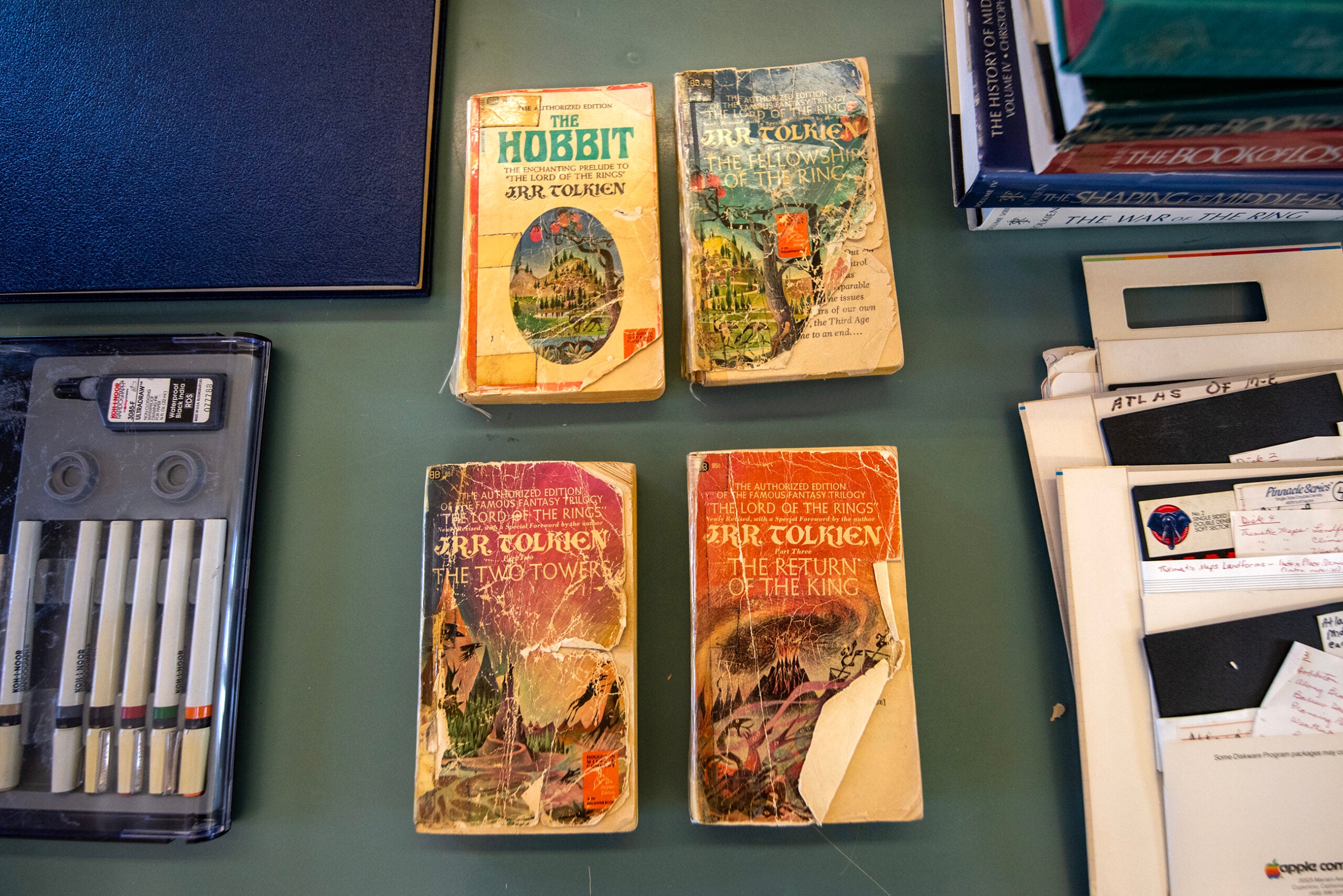

It was there that she first read the work of J.R.R. Tolkien, when a friend lent her a paperback copy of “The Fellowship of the Ring.”

“She ended up reading that particular book 30 times,” Todd said.

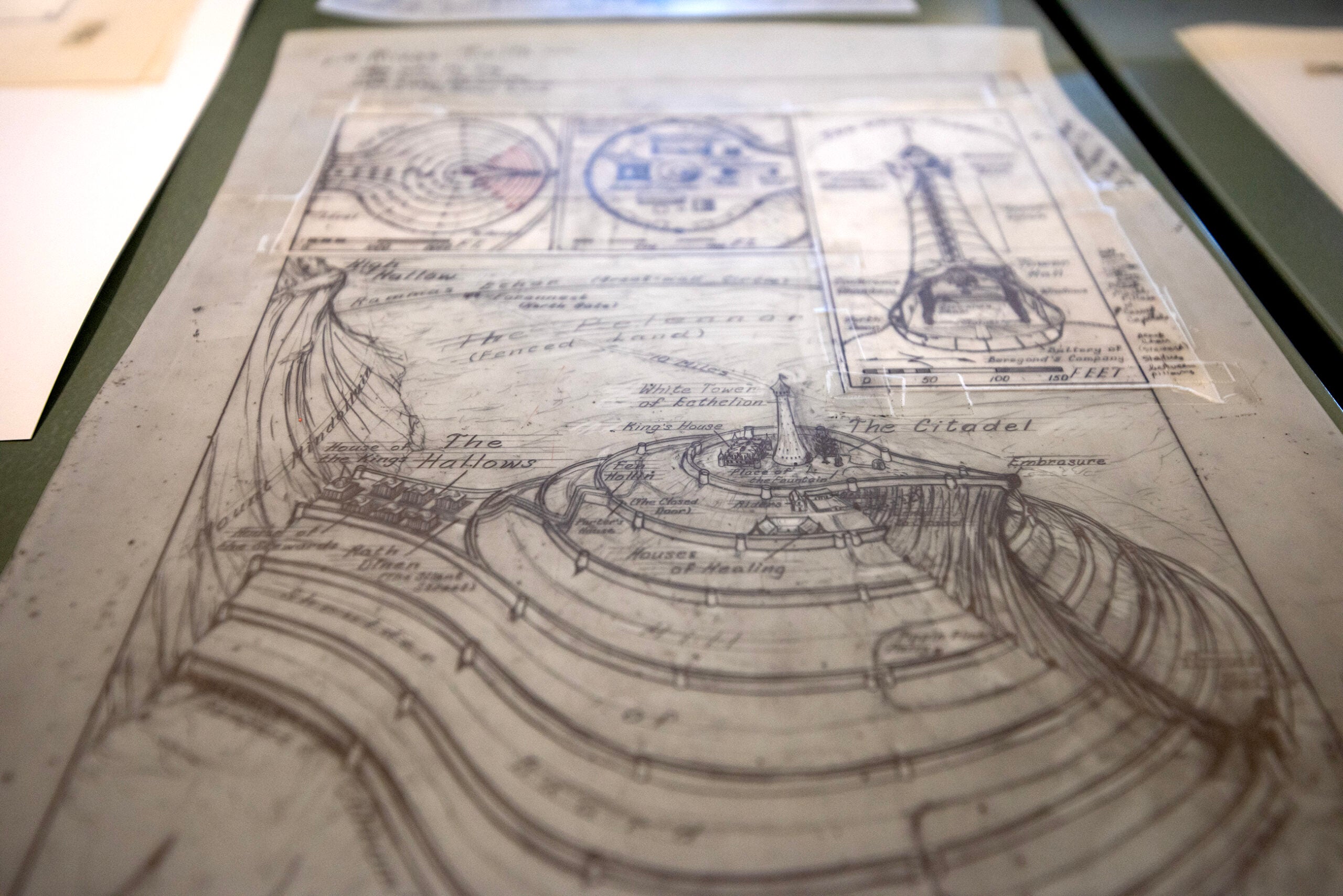

“The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy included maps created by Tolkien and his son, Christopher. But Karen wanted to go further — much further — with detailed maps of regions, battlefields, cities and more, inspired by geographic information in the text.

And she wanted to share those maps with the world. In 1977, she called the American publisher of Tolkien’s work, Houghton Mifflin, to pitch the idea of an atlas. As Todd recalled, the person in charge of handling Tolkien’s work fell in love with the idea, and the Tolkien estate gave it the thumbs-up.

Then the work really began.

The first step was to sift through the books for every geographical clue they had to offer. That included “The Hobbit,” “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy and “The Silmarillion,” a lengthy prequel work of Tolkien’s published posthumously in 1977.

“She reread Tolkien’s ‘Lord of the Rings’ books many, many times,” Mark said. “And she would take notes. She would underline phrases and sentences and paragraphs that had specific geographic information.”

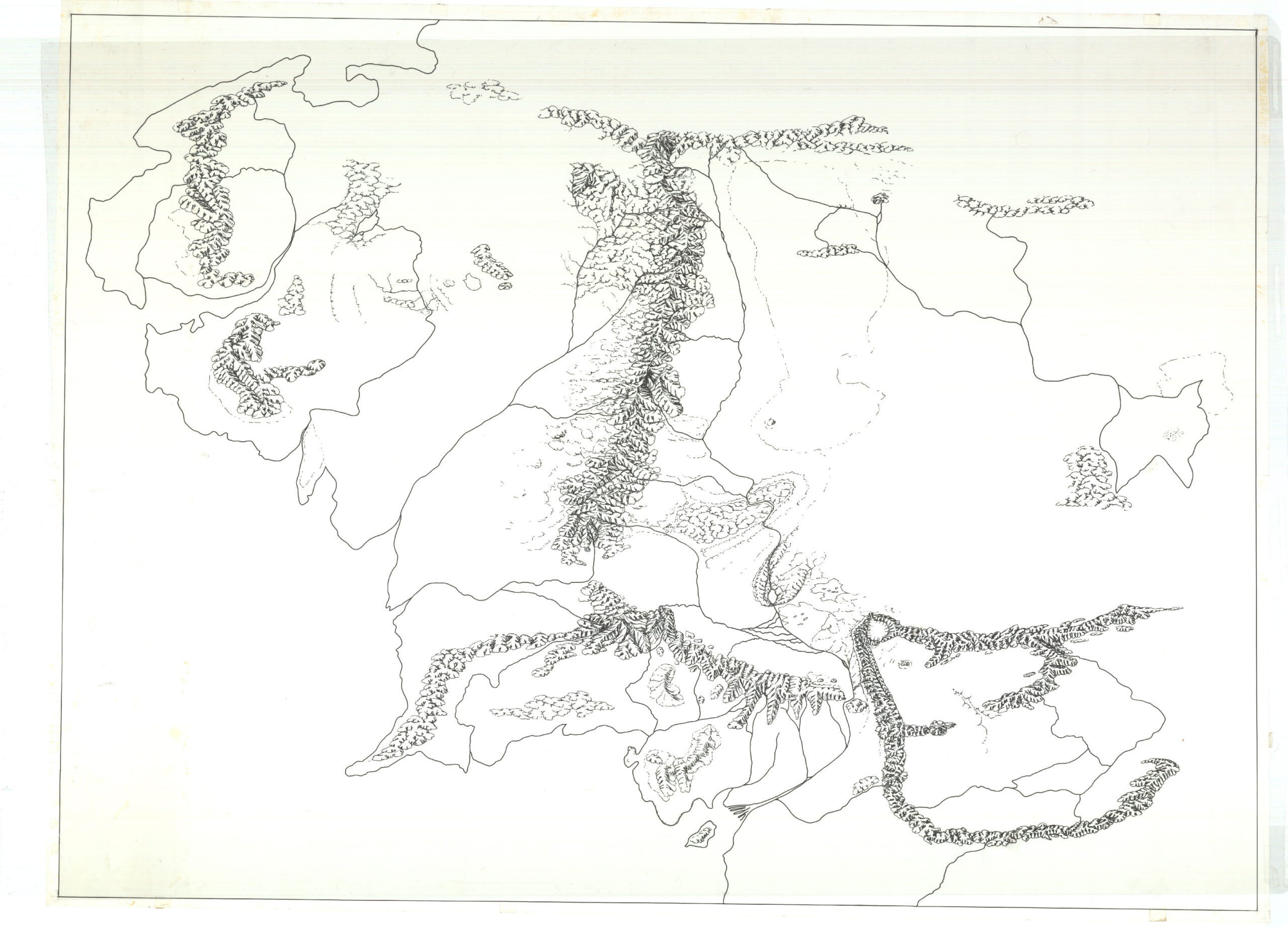

One of Karen’s first steps in creating the atlas of maps is now one of the largest items on display in Mark’s sprawling setup at the map library: the base map that was such a challenge to scan.

The base map took center stage on the floor of the Fonstads’ home.

“She started building this huge base map on the floor of the kitchen, using kitchen tiles as [a] scale,” Mark said. “She would then add information that she had read in the books.”

From there, she moved on to the more detailed and localized maps. When she was done, there were 172 maps, along with her extensive commentary on the geography of Middle-earth.

This was before computer graphics were an option. Karen drew all of those maps by hand.

“She was very handy,” Todd said. “She actually built a light table with her tools. I think Mark’s got it in his house right now. It eventually migrated from the kitchen floor to upstairs, where she could work till four in the morning.”

Beyond Middle-earth

Karen’s “Atlas of Middle-earth” was just the start of her career in fantasy mapmaking. She created a revised and expanded version of the atlas in 1991, using unpublished material from J.R.R. Tolkien that was released by the Tolkien estate.

She also created atlases for the worlds of fantasy authors Anne McCaffrey, creator of the “Dragonriders of Pern” series, and Stephen R. Donaldson, who wrote “The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant” series.

Unlike Tolkien, who had passed away, McCaffrey and Donaldson were at the time living authors, so Karen could pry extra details out of them for their atlases. Mark was able to accompany her on a trip to Ireland to work out those details with McCaffrey.

Those maps are also part of the collection at the UW-Madison map library. So are some never-before-published maps of Narnia. Karen had proposed an atlas of “The Chronicles of Narnia,” but the estate of author C.S. Lewis didn’t pursue the idea.

Karen’s fantasy mapmaking career coincided with a new industry that has strong roots in Wisconsin: role-playing games. So she was a natural fit to create maps and atlases for Dungeons & Dragons, published by the Lake Geneva-based company TSR, Inc.

The fantasy land of… Oshkosh?

We also saw one of Karen’s maps of a world a little closer to home: her update of the map of Oshkosh.

“My mother was never a full-time cartographer,” Mark said. “She would do a [Dungeons & Dragons] module now, or a book there, but she would also be working as a physical therapist or a lecturer at the university, teaching cartography.”

So, he said, “She would do projects that to other people might seem more mundane, like, ‘Let’s update the map of Oshkosh.’”

Todd said Karen was constantly busy, not just with her artistic projects, but in civic life in Oshkosh. She was a member of the city planning commission, active in church and spent a term on the Oshkosh Common Council.

“She was always on the go,” Todd said. “One of her favorite sayings was: ‘Can’t never did anything.’”

How fantasy maps ought to look

Karen’s impact on the world of fantasy map-making was huge. We realize this as UW-Madison geography student Reid Osborn peeks into the map library, and it sinks in what he’s looking at.

It turns out he is a huge Fonstad fan and is starstruck by the massive collection he has stumbled across.

“Is this happening?” Osborn said.

He’s not alone. Mark shared a quote from the most important audience of all — Christopher Tolkien, son of the author and manager of the works until his death in 2020.

“The Atlas of Middle-earth is very remarkable. The very publication of such a book in such elegant form, and the highly professional skill and care that Mrs. Fonstad has brought to its making is sufficiently wonderful,” Christopher wrote.

And Karen had fans, from readers of Tolkien to Dungeons & Dragons players, who used her work.

“I think she was quite taken aback by the public interest in her and her work at the time,” Mark said. “Because when she was working on these projects, mostly in the 1980s, she said, ‘I could have been on a desert island.’ It was just her and her maps and her light table and the drafting pens, and that was basically it.”

(She even inspired WPR’s Rob Ferrett to try his hand at fantasy mapmaking as a kid, despite his lack of ability at art, drafting or cartography. Those works will not be published in atlas form.)

Despite having a fan base, she avoided fantasy conventions for most of her life.

“It wasn’t until Peter Jackson’s ‘Lord of the Rings’ movies that she kind of got out of her skin and went to some of those conventions,” Mark said.

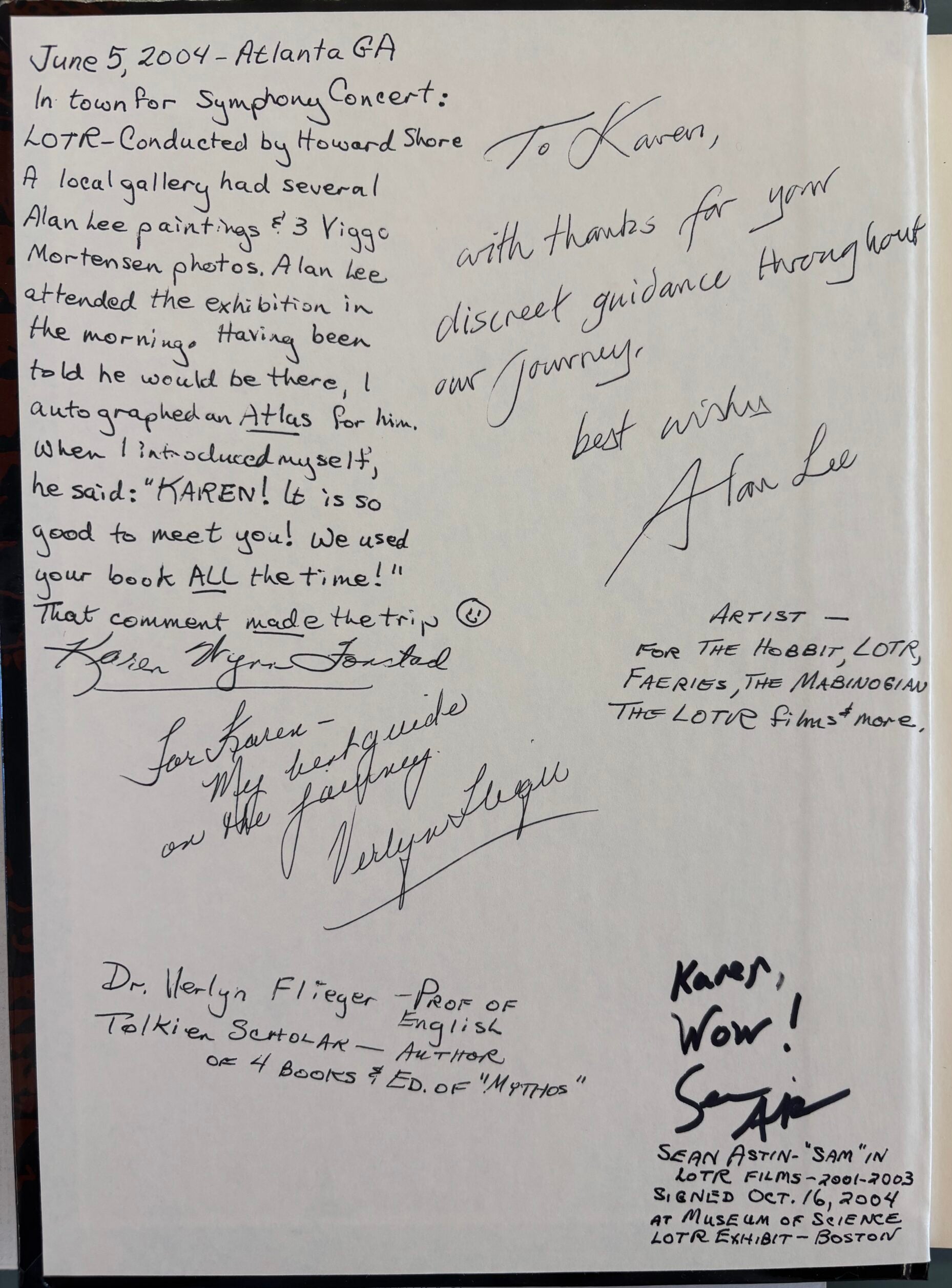

Those movies are part of her legacy, as the creative team behind the movie used her maps for guidance and inspiration. Alan Lee, one of the lead concept artists for Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” films, signed Karen’s copy of the atlas: “With thanks for your discreet guidance throughout our journey.”

Karen Wynn Fonstad died of breast cancer in 2005. As Todd recalls, the last few months of her life were the first time he saw her slow down.

Mark and Todd agree the legacy of her work lives on.

“I think she would be utterly surprised, to say the least, to see how this has ballooned,” Todd said. “You know, she never did this for money or for fame. It was her passion.”

They’re looking to preserve that legacy with their current project to digitize her work and find a permanent home in an archive for the maps spread over the map library during our visit.

“People spend a lot of time looking at my mother’s work as a kind of benchmark. Like, ‘This is how fantasy maps ought to look,’ in some respect,” Mark said. “If you go ask people who do fantasy cartography as a hobby, my mother’s work is often the very first thing that comes up. I think she would be very happy about that.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.