Scott Nicol returned to his hometown of Tomah in 1973 to work as a dentist. He was fresh out of dental school, and he remembers one of his first patients: an older man who needed a denture fixed but was skeptical about getting treatment from a young provider.

“Then he said, ‘Are you Bob and Junie’s boy?’ And I said yes,” Nicol recalled. “He said, ‘Go ahead and fix it.’”

Nicol found building good relationships with his patients and office staff was the key to success as a small-town dentist. He would spend more than four decades caring for the residents of his community in western Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But when it came time for Nicol to retire, finding someone to take over his portion of Tomah Family Dentistry wasn’t easy.

He spent more than two years looking for the right dentist to take his place, even turning down offers from dentists who he knew were only looking for a temporary job. Nicol found there were few young dentists looking to move permanently to a rural city of fewer than 10,000 people.

In the last five years, Wisconsin’s dental industry has gone through a major shift as more providers from the baby boom generation leave work. The natural transition was accelerated even further by the COVID-19 pandemic, when many dentists chose to retire earlier than usual.

For patients, that can mean difficulties finding care amid dental shortages.

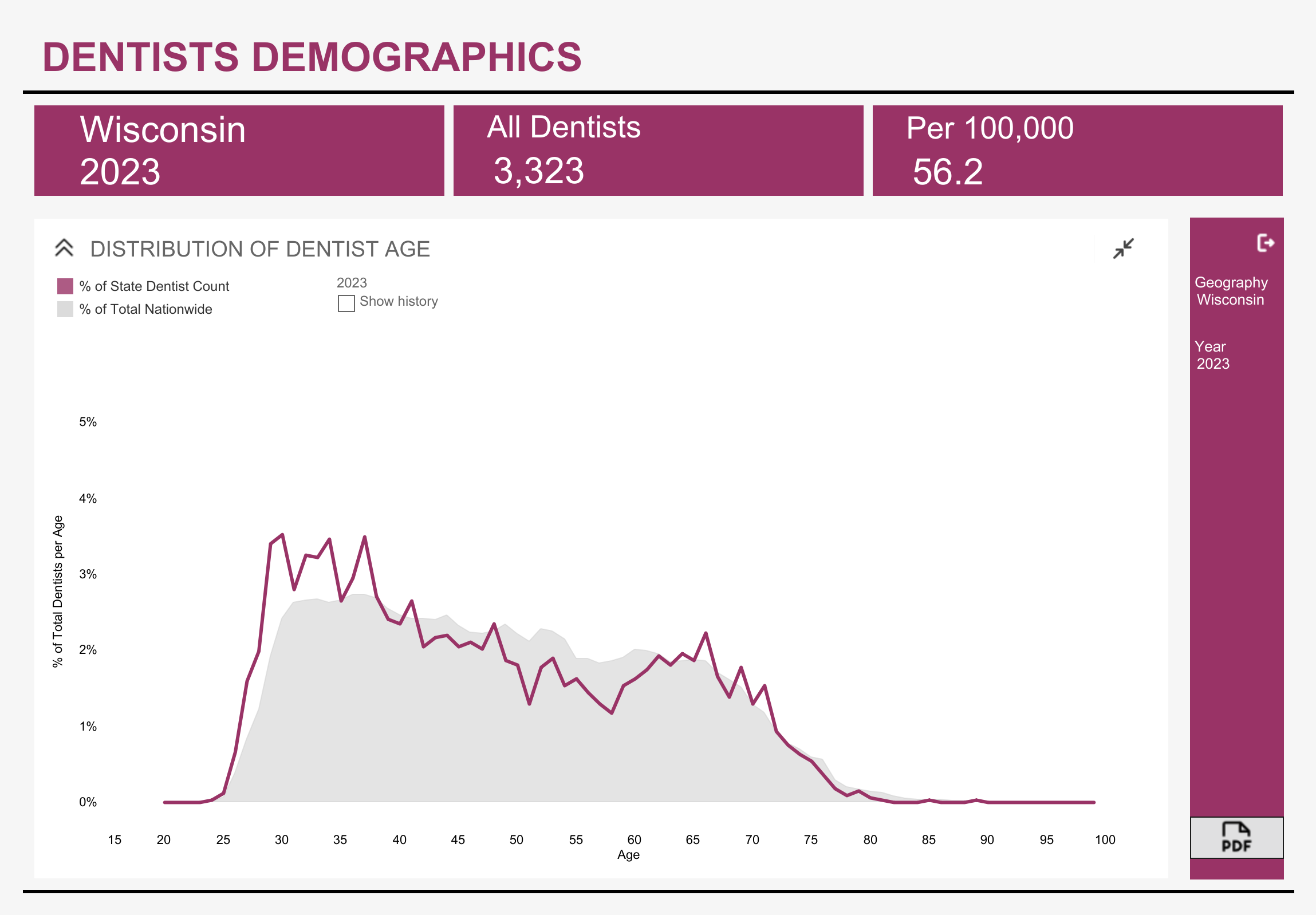

According to data from the American Dental Association, in 2020, a third of the state’s dentists were baby boomers and another third were millennials.

By 2023, millennials made up nearly half of the state’s providers while baby boomers represented about a quarter of Wisconsin dentists. As more boomers reach retirement age (the youngest members of the generation are now 60), that transition will continue in the coming years.

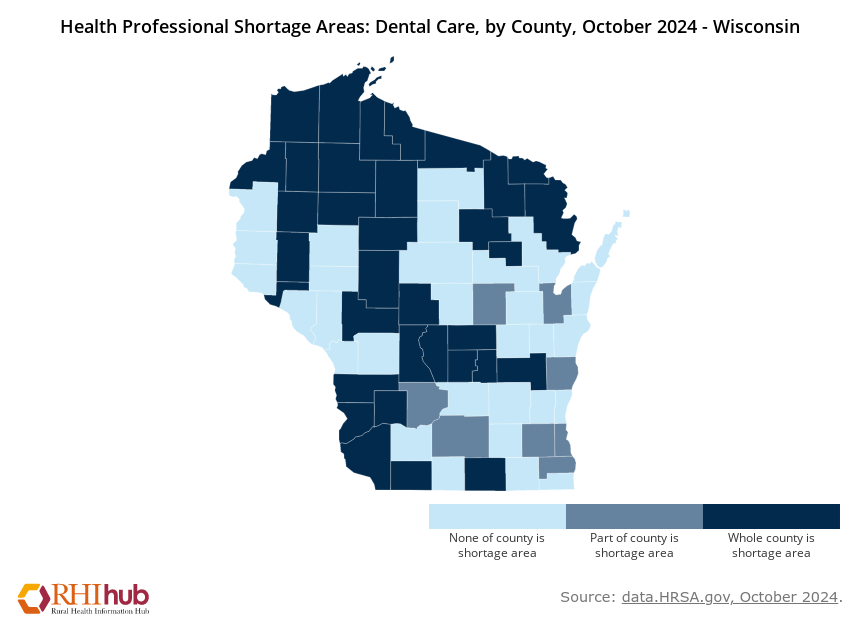

This generational change has affected rural areas of the state the most, where there is already a shortage of dentists. Without new providers coming, rural patients are left with fewer options for care and longer wait times for an appointment.

“The biggest challenge I have seen over the years in getting a dentist to come to a smaller town is their spouse doesn’t want to live here,” Nicol said. “They’re looking for something more than what a Tomah has to offer.”

Young dentists balance higher debt, desire for mentorship

American Dental Association data shows Wisconsin has largely the same number of dentists per capita as it did 20 years ago, after numbers fell slightly in the late 2000s. Industry leaders say many young dentists are looking at the state’s cities, attracted by the amenities of urban life and better job opportunities for their spouses.

Many graduates are also leaving dental school with a large amount of debt. Nicol said that not only makes it harder for them to buy into or start a private practice, but also influences the way new dentists think about their first jobs.

“A lot of them are just looking for a place to get experience, make some money, pay down their debt, and then they’re going to move on,” he said.

For some dentists, that means working for a corporate chain, or what are known as dental service organizations, instead of owning and operating an independent business. Nicol said he’s seen many retiring dentists choose to sell to corporate chains after failing to find someone to take over their private practice.

Wisconsin is one of 26 states that have seen dentists at the beginning of their careers leave for jobs in other states. Data from the American Dental Association shows that between 2019 and 2022, Wisconsin lost more than 2 percent of new dentists, or those with less than 10 years of experience. It’s one of the smaller net losses, with some states losing 7 percent or more of young dentists.

Lauren Poppe graduated from Marquette University’s School of Dentistry, the only dental program in Wisconsin, in 2024. She said the majority of her classmates stayed in urban areas for their first job. But the decision was as much about their careers as it was about their lifestyle.

“I think some of my classmates thought that maybe they would get more experience in an urban location, and be able to build more confidence,” Poppe said.

Poppe is one of the exceptions. She started working for a small dental practice in rural Douglas County right after graduation, a job that has provided the mentorship she said many new dentists are looking for.

But Poppe said there are only a few other dental providers in her area, limiting opportunities for other new dentists to find the same start.

Of Wisconsin’s 45 rural counties, 30 are considered a dental health professional shortage area, according to federal data from October. By comparison, four of the state’s 27 metropolitan counties were shortage areas.

Poppe said the shortage means more people are relying on her for care, a position that can feel intimidating for any new graduate. There are only a handful of specialists like orthodontists to whom she can refer people, and her office pulls in patients from as far as an hour and half away.

“If a patient walks in your door and you haven’t seen something like that, or you’re not quite sure, having someone you can call and talk to, bounce ideas off of, that’s the reason why I wanted to go to a practice that wasn’t just me,” she said.

State officials work to incentivize rural practice

Poppe was able to start working in rural Wisconsin right away thanks to a new state incentive referred to as diploma privilege.

The Wisconsin Dentistry Examining Board voted in 2023 to allow Marquette graduates to skip the practical exam that’s normally required for state licensure, helping graduates get licensed more quickly. It’s the first program of its kind in the nation, according to Marquette.

Poppe’s class last spring was the first group of recipients, with 24 students out of the class of 100 participating. While most grads wait six to eight weeks for a license to practice, Poppe said she received hers three days after graduation. She thinks the expedited process will be a significant incentive for future graduates to stay in Wisconsin immediately after graduation.

State officials have also taken action to try to get new dentists to where they’re needed most. Last year, state lawmakers changed an existing state scholarship for health care workers to be specific to dental students at Marquette.

The scholarship awards $30,000 to 15 students annually. In exchange for each year they receive the scholarship, students agree to work for 18 months in a dental health shortage area outside of Brown, Dane, Kenosha, Milwaukee and Waukesha counties.

Wisconsin also began licensing dental therapists in 2024. These mid-level providers work under the supervision of a dentist to provide care like filling cavities or placing temporary crowns. Many health advocacy groups in the state have supported the new type of provider as a way to expand care in areas where dentists are in short supply.

Recruiting small-town dentists may be easier at home

After two years of searching, Nicol ended up finding his successor in a former patient at his office.

Lucas Schwartz spent a lot of time going to the dentist as a kid because of a unique health condition. But his dentist, Nicol’s partner Mark Matthews, made the experience fun— so much so that Schwartz decided to pursue his own career in dentistry, with a goal of returning to a small town like one he grew up in.

“There’s a lot of community, that’s probably the biggest thing,” Schwartz said. “I mean, you talk to regular people like your mailman every day, and you get to know who they are.”

He said only a handful of people in his dental class at Marquette were from rural areas, and many of his classmates looked for more secure jobs in cities to pay down their student debt. But Schwartz said the state’s incentives have helped rural jobs look more attractive, adding he benefited from the state scholarship for working in health shortage areas before graduating in 2022.

Schwartz credits Nicol for passing on a thriving private practice and a good example for how to be a successful provider in their shared hometown.

“Treatments may have changed, but having patient rapport, talking to people and having that connection, is still the best value I think that dentistry has, especially in a family clinic,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.