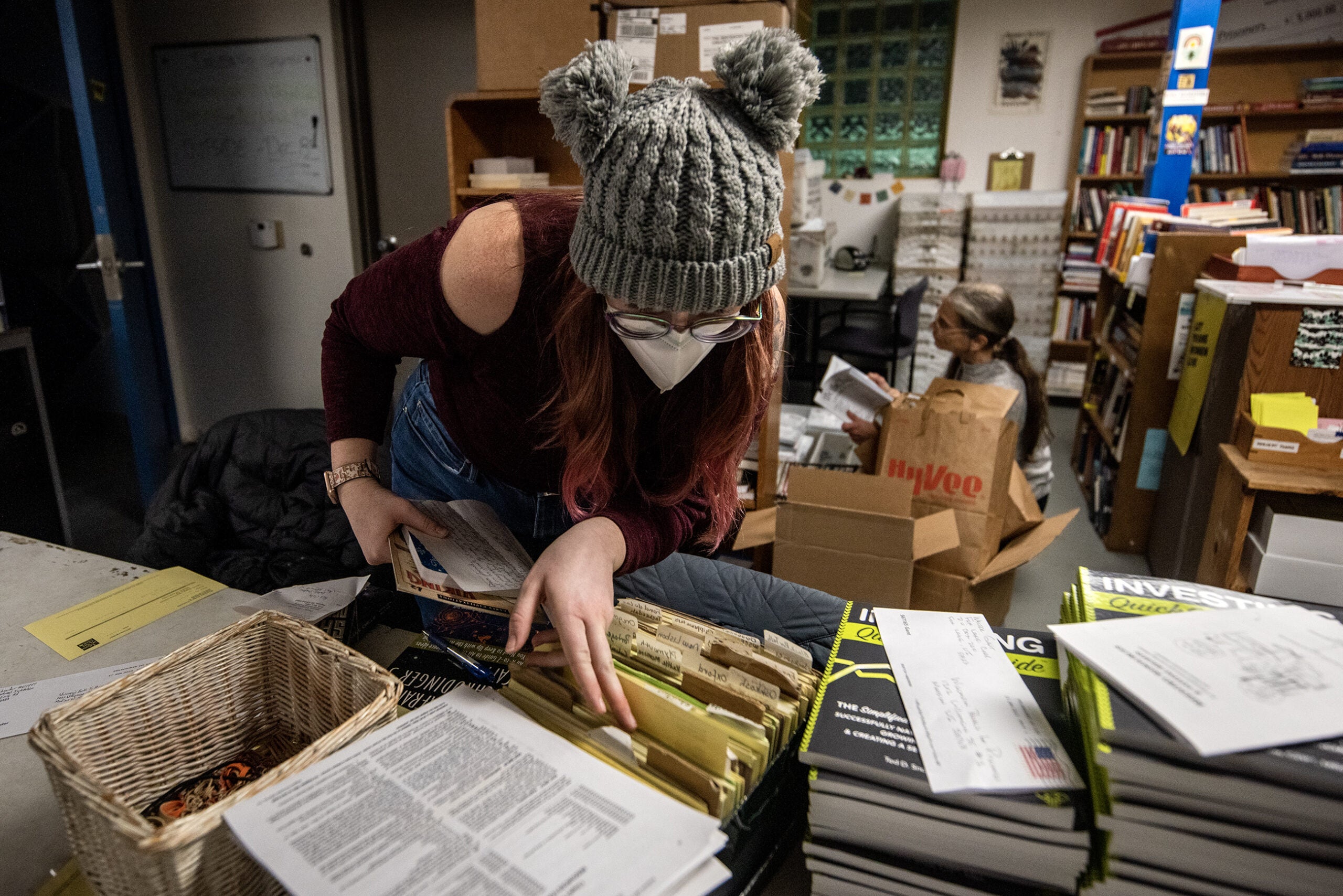

A Madison-based nonprofit has stopped sending free books to Wisconsin prisoners after the state’s Department of Corrections imposed new restrictions.

Since its inception in 2006, Wisconsin Books to Prisoners has sent more than 70,000 books to people locked up across the state.

But earlier this year, prison officials told the group of volunteers they had to stop their longstanding practice of mailing gently-used books to inmates who request them.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The new restrictions have been devastating, Books to Prisoners Co-Founder Camy Matthay said in an interview with WPR.

“Reading in prison, in a sense, makes our communities safer because prisoners are returning more prepared to contribute to their communities as valuable members,” she said. “Our point of view is that reading is a human right, and access to books of your own choosing should be a right as well.”

In emails to the nonprofit, DOC officials cited concerns about people smuggling in drugs by pretending to be affiliated with Books to Prisoners.

“There have been many instances of drugs coming in via mail (and publications/books) which appear to be sent from the Child Support Agency, the IRS, the State Public Defender’s Office, the Department of Justice and individual attorneys,” Division of Adult Institutions Administrator Sarah Cooper wrote in an Aug. 16 email. “In reality, the mail pieces are not from those agencies, but from the bad actors who imitate them to send the drugs in. So our concern is not with your organization, but with those who would impersonate your organization for nefarious means.”

In response to follow-up questions from WPR, DOC spokesperson Beth Hardtke said problems have also been flagged from mail purporting to be from Books to Prisoners.

“In February, multiple books in two separate shipments allegedly from Wisconsin Books to Prisoners tested positive for drugs at Oshkosh Correctional Institution,” Hardtke wrote in an email to WPR on Thursday.

Prison officials say new books purchased through approved vendors are OK

In January, prison officials notified Wisconsin Books to Prisoners that, going forward, the group could only send brand-new books purchased through pre-approved vendors.

That prompted Books to Prisoners to propose an alternative arrangement after researching how prisons in other states handle donated books.

The DOC could put Wisconsin Books to Prisoners on a “trusted sender list with special permission to continue sending clean copies of used books given our unblemished record of acting in accordance with federal and state policies since our inception in 2006,” Matthay suggested in a July email to prison officials.

But Cooper wrote back in August, saying the DOC wouldn’t make an exception.

“In fact, since the decision was made to no longer allow books in from your organization, we’ve had to implement a whole new process for

handling mail,” from multiple entities including the IRS and the State Public Defender’s Office, Cooper wrote.

In an interview with WPR, Matthay said Books to Prisoners interpreted that sentence in the August email to mean Books to Prisoners could no longer send any books, whether used or new.

That’s not the case, Hardtke said. The DOC allows people to send new books to their incarcerated loved ones by buying the publication through a pre-approved vendor, and Hardkte said Books to Prisoners could follow those procedures. Those new books arrive directly from the vendor with a receipt attached.

“Wisconsin Books to Prisoners could send new books into our facilities following the same rules as everyone else,” Hardtke wrote in an email this week. “It is inaccurate to say that the organization is banned.”

Even so, Matthay says a new-books-only policy would force Books to Prisoners to severely cut back its operations.

“We’d be able to send only a very, very few titles,” Matthay said in an interview with WPR. “It’s challenging raising money for prisoners (and) it would depend on funding.”

Occasionally, Matthay said Books to Prisoners sends new books that are donated by publishers or purchased by a patron. But the vast majority of the books come from community members who drop off their second-hand paperbacks.

The prison system is working with Books to Prisoners to find a solution, Hardtke said this week.

“It is DOC’s great hope that we can find a way for them to provide books to support the reading needs and education of the persons in our care in a way that is safe,” Hardtke told WPR.

Books to Prisoners considering legal action

Meanwhile, Matthay said her group has been in contact with the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin about possible legal action, alleging that the DOC violated Books to Prisoners’ First Amendment right to distribute literature.

“People in prisons already have extremely limited access to educational materials, and it is incredibly harmful to further limit their basic right to information through indiscriminate, unfounded mail policies,” the ACLU said in a statement this week. “The services provided by non-profit organizations to increase access to these materials are commendable and should be encouraged, not banned. We are currently investigating the issue.”

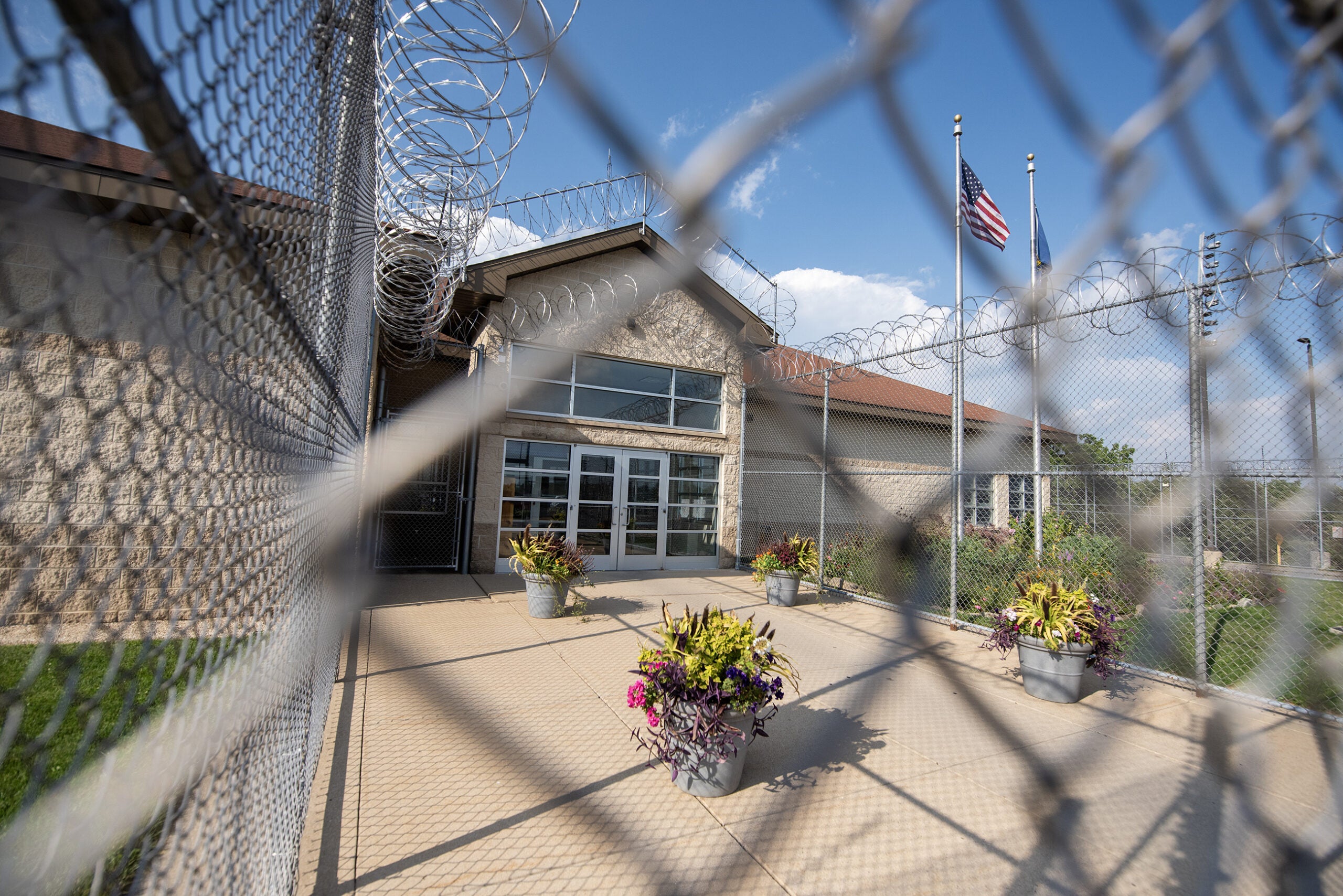

In recent years, the DOC has been tightening up its rules to prevent drug smuggling into prisons, and Hardtke said the latest restrictions on books are part of that effort.

Three years ago, the department began contracting with a company that scans incoming prison mail, so inmates get photocopies of their mail instead of the original paper.

“DOC has seen an increase of drug incidents among persons in its care, including increased use of K2 and other synthetic cannabinoids, which have no odor and can be difficult to detect,” the DOC wrote in a 2021 news release about the change. “Paper and envelopes can be sprayed with or soaked in these drugs. This paper is then sent into DOC institutions via mail, where some persons in DOC care tear it into small strips, and use it or sell it to others.”

In 2022, the department announced updates to its screening procedures for staff, volunteers and other visitors entering prisons. And, earlier this year, the department increased its oversight over legal mail, as well, Hardtke said.

“Legal mailings shall be opened in the presence of PIOC and shall be treated as confidential,” the recently-updated policy says, referring to inmates by an acronym for persons in our care. “Staff may inspect legal documents for discrepancies, but only to the extent necessary to determine if the documents contain contraband or if the purpose is misrepresented. Staff may read the legal documents if they have reason to believe it is something other than a legal document and the safety and security of the institution is implicated.”

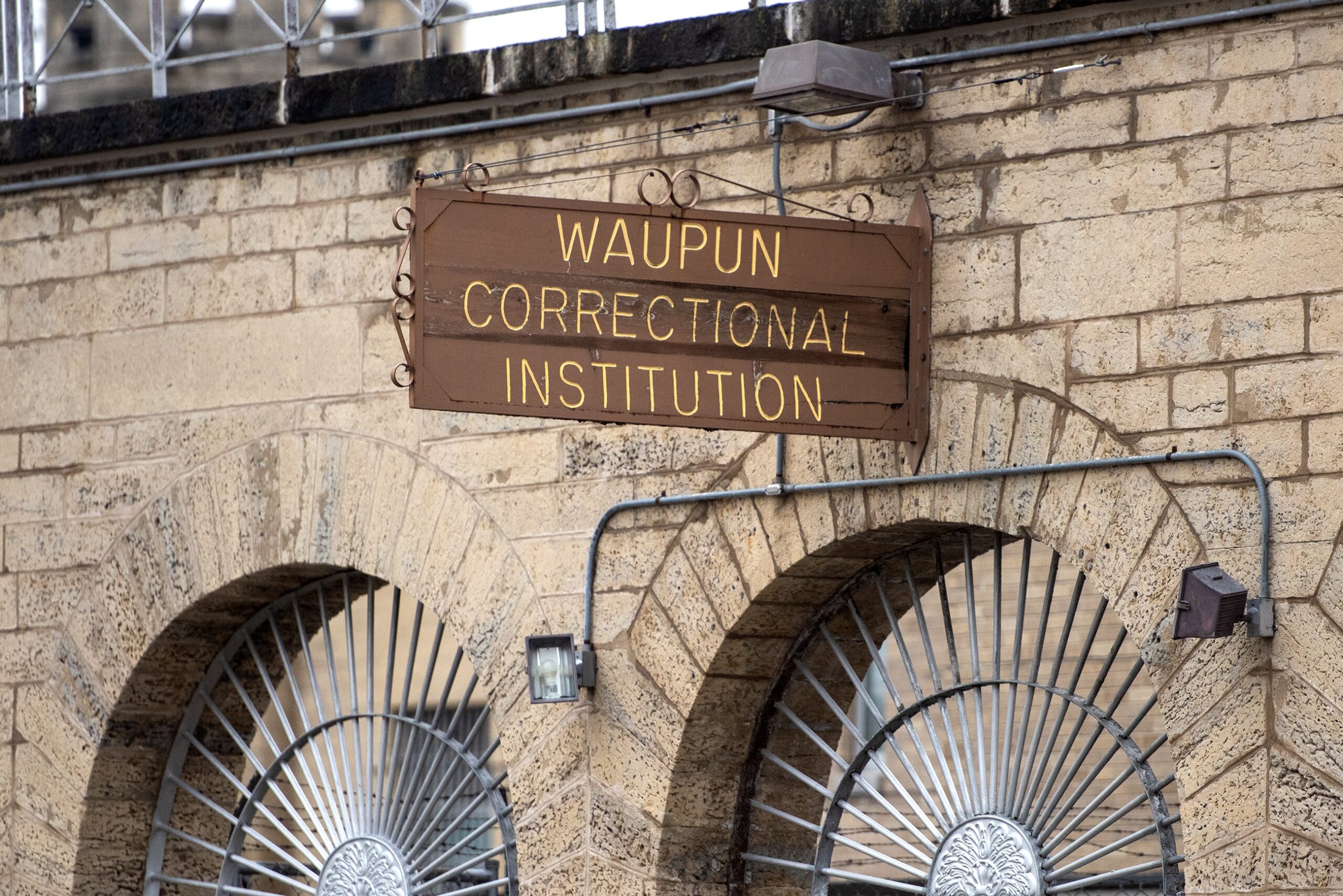

In March, Gov. Tony Evers confirmed that federal law enforcement has been investigating allegations that employees of the Waupun prison smuggled drugs and cell phones into the maximum-security prison.

Hardtke declined to say whether the recently-imposed restrictions on books were prompted by the investigation into Waupun staff.

“The Department of Corrections (DOC) fully supports the educational goals and aspirations of persons in our care and believes in the power of reading to change lives and aid in rehabilitation,” Hardtke said in a statement, adding that inmates have access to prison libraries and to materials needed for educational courses.

“In addition to supporting this important goal, DOC’s primary responsibility is to keep those in our care, our staff, and our communities safe,” she continued. “Drugs smuggled into DOC facilities pose a clear risk to the lives and health of those in our institutions.”

Incarcerated people write in with hundreds of book requests every year

Over the course of Books to Prisoners’ 18-year- history, there have been two other times when the DOC has warned the organization it would have to stop or change its operations — once in 2008 and once in 2018, Matthay said.

But Matthay said the group was twice able to resolve the issue. In the past, she said Books to Prisoners worked with the ACLU, and the DOC agreed the group could send used books, as long as those publications were in good condition.

Books to Prisoners sends titles to incarcerated people who write to the organization, asking for books with specific titles or on specific topics.

The most common request is a collegiate dictionary, followed by requests for instructional manuals for learning trades.

“During Covid, we were getting letters from prisoners who are saying, ‘Your service is absolutely critical to my emotional well being,’ you know, ‘Grace be to you,” Matthay said, adding that the organization averages about 50 requests every week. “Prisoners love to read. … The reading interests of prisoners is as broad as that of the patronage of any public library.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.