Jarrett Adams spent seven years of his young life in prison for a crime he didn’t commit — and didn’t see a cent of compensation. Now, he’s an attorney helping two Green Bay brothers seek their own compensation for the 24 years they spent behind bars.

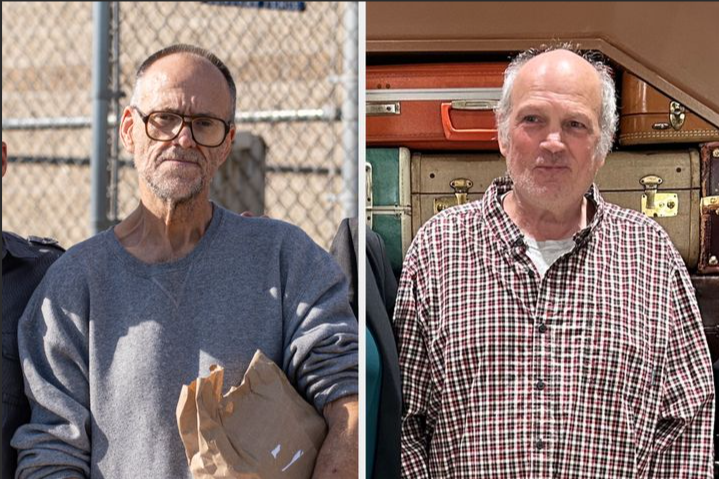

Robert and David Bintz were released from prison last year at the ages of 68 and 69, after DNA evidence helped exonerate them of the 1987 murder of Sandra Lison. Adams is petitioning the Wisconsin’s Claims Board, on behalf of the Bintz brothers, for a little over $2.1 million each.

Adams calls it a “historic” amount — if granted, it would be the highest amount of compensation ever awarded to someone wrongly convicted in Wisconsin. That record is currently held by Daryl Holloway, who in 2022 was awarded $1 million plus $100,000 in attorney’s fees for the 24 years he spent in prison.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Adams’ argument: Because they’re older than many other exonerees, Robert and David don’t have the ability to get back on their feet.

“[Robert] and David are home at 70 years old. There’s nothing they can do right now besides have their hands out and beg the community to push the legislators and everyone else to fix this situation for them,” Adams told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

An exoneree himself, Adams said that while his wrongful conviction harmed him, he had a privilege that Robert and David don’t: time.

His youth ahead of him

Nineteen-year-old Adams was convicted of sexual assault by an all-white jury in 2000 and sentenced to 28 years in prison. He spent seven years there.

Adams sought help from the Wisconsin Innocence Project, and in 2007 the the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit vacated Adams’ conviction, citing insufficient evidence and ineffective counsel, after Adams’ lawyer failed to locate and call a key witness.

“The conviction is reversed. I come home, but the damage is not reversed,” Adams said.

When he was released, Adams went to stay with his mother and stepfather, picking up odd jobs like cleaning gutters and hanging TVs to support himself through community college at night. At the encouragement of his aunt, he started going to therapy.

But any support Adams received was from his community, not from the state. Two years after he was released, Wisconsin’s Claims Board denied his request for monetary compensation for his time spent in prison, deciding that he didn’t clear the bar of having “clear and convincing evidence” to support his innocence.

“One of the board members told me, ‘I’m sorry this happened to you. Good luck in life.’ And that was almost like a slap in the face to me,” Adams said. “[Compensation] would have helped me get back on my feet.”

But Adams had time on his side.

“I had something that most people who go through this don’t have, and that’s their youth ahead of them,” Jarrett said.

Adams eventually attended the Loyola University Chicago School of Law, with the intention of eventually defending other people in his situation.

“I was at a breakneck pace to get my law degree because I wanted my mom and my aunt to be proud of me, and know that supporting me for years wasn’t for nothing,” Adams said.

He graduated in 2015 and went on to work for the Innocence Project in New York, where he helped exonerate Richard Beranek, who was serving time at the same Wisconsin facility where Adams was imprisoned.

Adams later opened his own law firm, established a nonprofit called Life After Justice and wrote a memoir titled “Redeeming Justice” that came out in 2021.

Wisconsin falls behind

In 1913, Wisconsin became the first state to provide compensation for people who spent time in prison for crimes they didn’t commit. Back then, the maximum amount that could be awarded was $5,000 total, or a little more than $160,000 in today’s money.

In more than a century since then, that amount has only been updated once: In 1979, the total compensation maximum was raised to $25,000, where it still sits.

According to a new data analysis from Wisconsin Watch, Wisconsin went from being on the cutting edge to having the second lowest rate of compensation in the U.S., among states that have wrongful conviction compensation laws.

The federal government offers $50,000 — per year spent incarcerated — for those exonerated in the federal system.

As Wisconsin Watch fellow Khushboo Rathore told “Wisconsin Today”: Wisconsin stacks up “really, really terribly.”

According to Rathore’s analysis, the average amount paid to exonerees per year spent incarcerated in Wisconsin is $4,200. And that’s only exonerees that receive compensation. Since 1989, only 41 percent of exonerees in Wisconsin filed claims, and 65 percent of those were actually awarded.

“But a lot of those people didn’t receive the full amount they asked for,” Rathore said. “They may receive very minor amounts, or just attorney’s fees in some cases.”

Unlike some states, Wisconsin also doesn’t provide non-monetary compensation to help exonerees re-integrate into society, like offering help with housing, higher education and health care.

Adams said Robert Bintz needs help with housing, especially.

“With Bobby, who’s sickly, it’s hard to find places that will accept his $600 to $700 a year of benefits money that he’s able to get,” Adams said.

Searching for more

Wisconsin’s Compensation Board is able to recommend that the Legislature award more than the $25,000 maximum compensation in cases where it deems the maximum inadequate — which is what the Bintz brothers are seeking.

However, the decision is at the board’s discretion, and it does so only in rare cases.

In 2015 and 2017, Wisconsin lawmakers introduced bills that would have raised the maximum compensation amount to $1 million, added additional non-monetary support and made it easier to raise the maximum amount in the future. Neither bill became law.

Adams testified in favor of the 2015 bill, which passed the Assembly unanimously but died in the Senate. Through his work with Life After Justice, which provides mental health resources and researches the needs of exonerees, he’s hoping to change Wisconsin lawmakers’ minds.

“As we collect the data, we serve as an example to influence and argue to the legislators that this needs to happen,” Adams said. “This can save lives and it can protect communities, and that’s what you swore to constituents that you would do.”