What constitutes “folk music”?

Though musical genres are, by nature, difficult to define, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor emeritus Jim Leary gave WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” a fairly succinct answer: “Fundamentally, folk music is the grassroots music; the musical vernacular of distinctive locales and cultural groups.”

Today, some Wisconsinites may think of Eau Claire band Bon Iver or the Violent Femmes from Milwaukee as local examples of folk music. Or perhaps they would cite Síle Shigley’s curations played on WPR’s “Simply Folk.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The Wisconsin Folksong Collection offers these and other examples a rich historical context. In separate endeavors, UW faculty member Helene Stratman-Thomas and ethnographer Sidney Robertson Cowell traveled the state and its borders between 1936 and 1947 to record performances of more than 900 tunes.

The collection comprises stories, memories, melodies, instruments and voices of the past — echoes of the Wisconsin Idea.

Now, the National Recording Registry is charged with the preservation and safekeeping of this part of Wisconsin’s history.

That is largely due to the three years Leary and other scholars spent advocating for its inclusion. To Leary, the collection itself is an incredible feat.

In the first half of the 20th century, Leary said, the effort to document and archive cultural artifacts and recordings in the Library of Congress was mostly spent on works by Anglo Americans and African Americans, and were largely in English. The music in different languages of immigrants and Native Americans were “siloed away.”

“But the Wisconsin Folksong Collection brought all of that together,” Leary said.

The project was put on hold during World War II.

“Many of the people who sang were descendants of countries that had been occupied by the Nazis,” Leary said. “They invested some of their songs with a powerful sense of love for their home country, but also pride in being in the United States.”

Nicki Saylor, director of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, told “Wisconsin Today” that the performers’ next of kin have come in person to the research center to listen to the original recordings.

“It means a lot to them personally and to their community,” Saylor said.

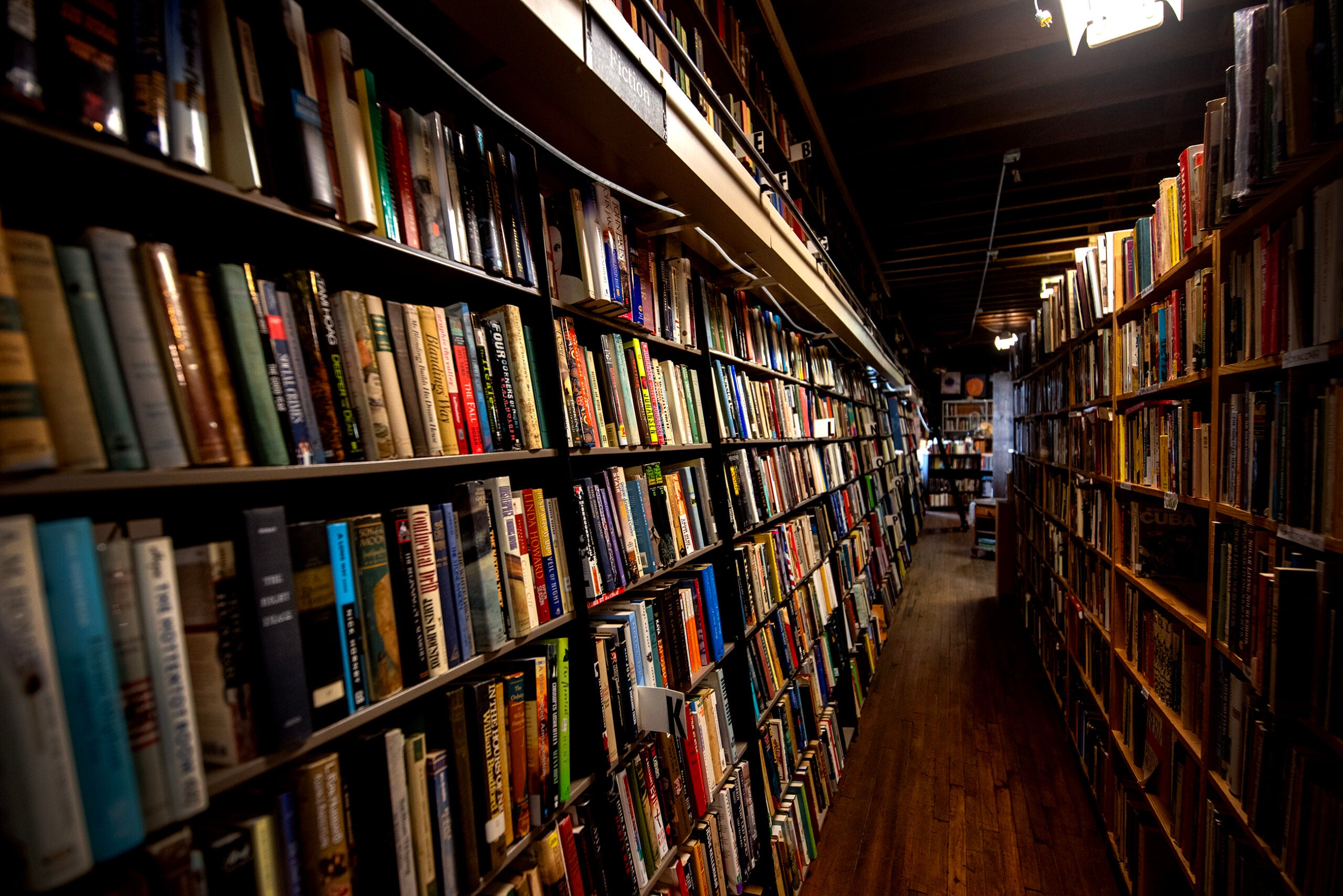

The collection can also be accessed online for free thanks to the Mills Music Library.

This article had been edited to correct the spelling of Sidney Roberston Cowell’s first name.