State Archaeologist Amy Rosebrough never heard of a “Ronksville” in Wisconsin until the descendants of brothers Nicholas and Paul Ronk contacted the Wisconsin Historical Society.

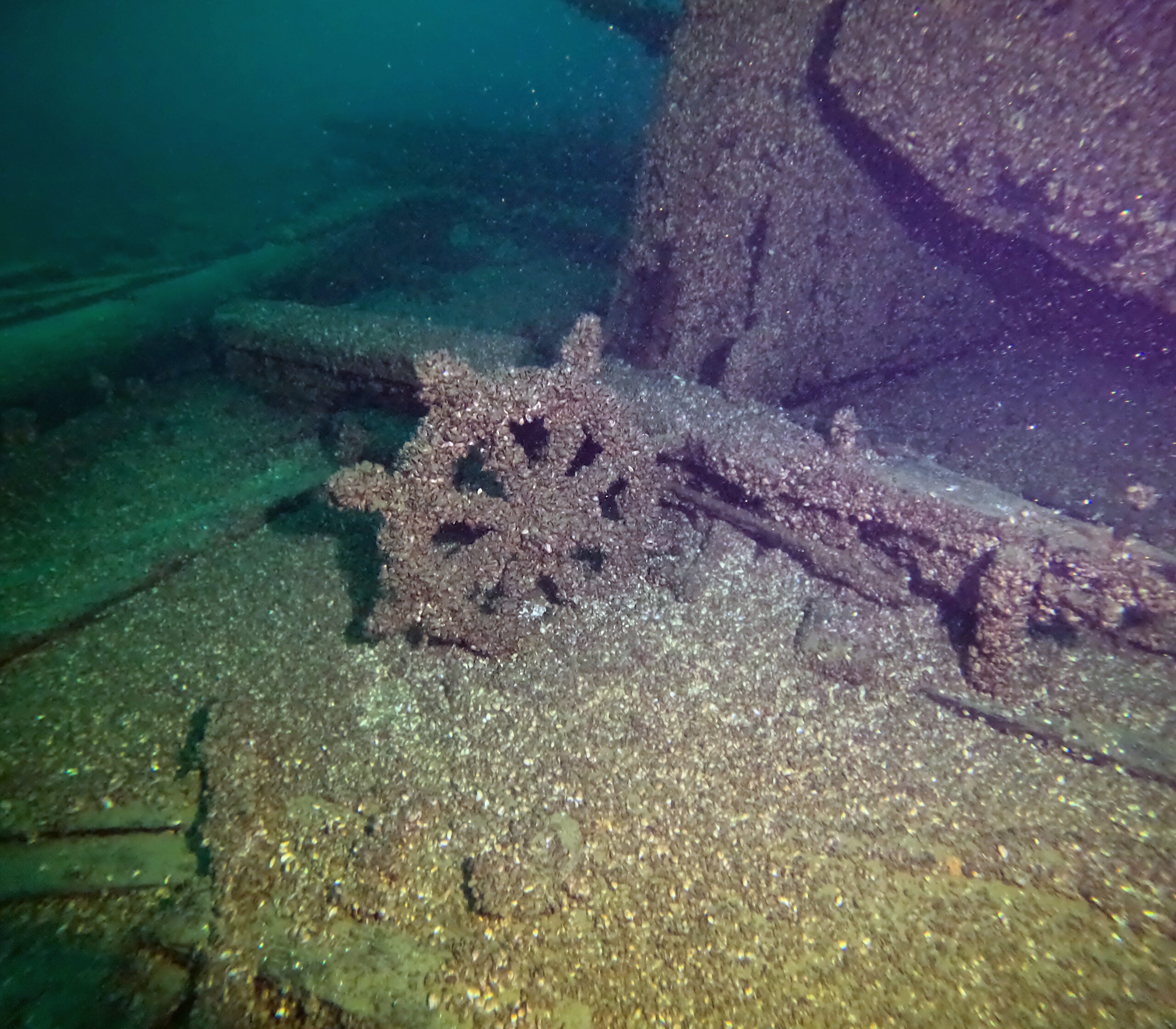

The descendants requested copies of a society poster featuring the wreck of a schooner called “Northerner.” Nicholas Ronk was the last known owner of the ship.

The Ronk brothers, Rosebrough would learn, founded the Luxemburger Pier Company of Ronksville in 1858. But their descendants had no idea where in Wisconsin this eponymous community once existed.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Rosebrough’s team used old property deeds, navigational charts and historic plat maps to approximate that a Ronksville pier may have been located in the modern community of Lake Church in Ozaukee County.

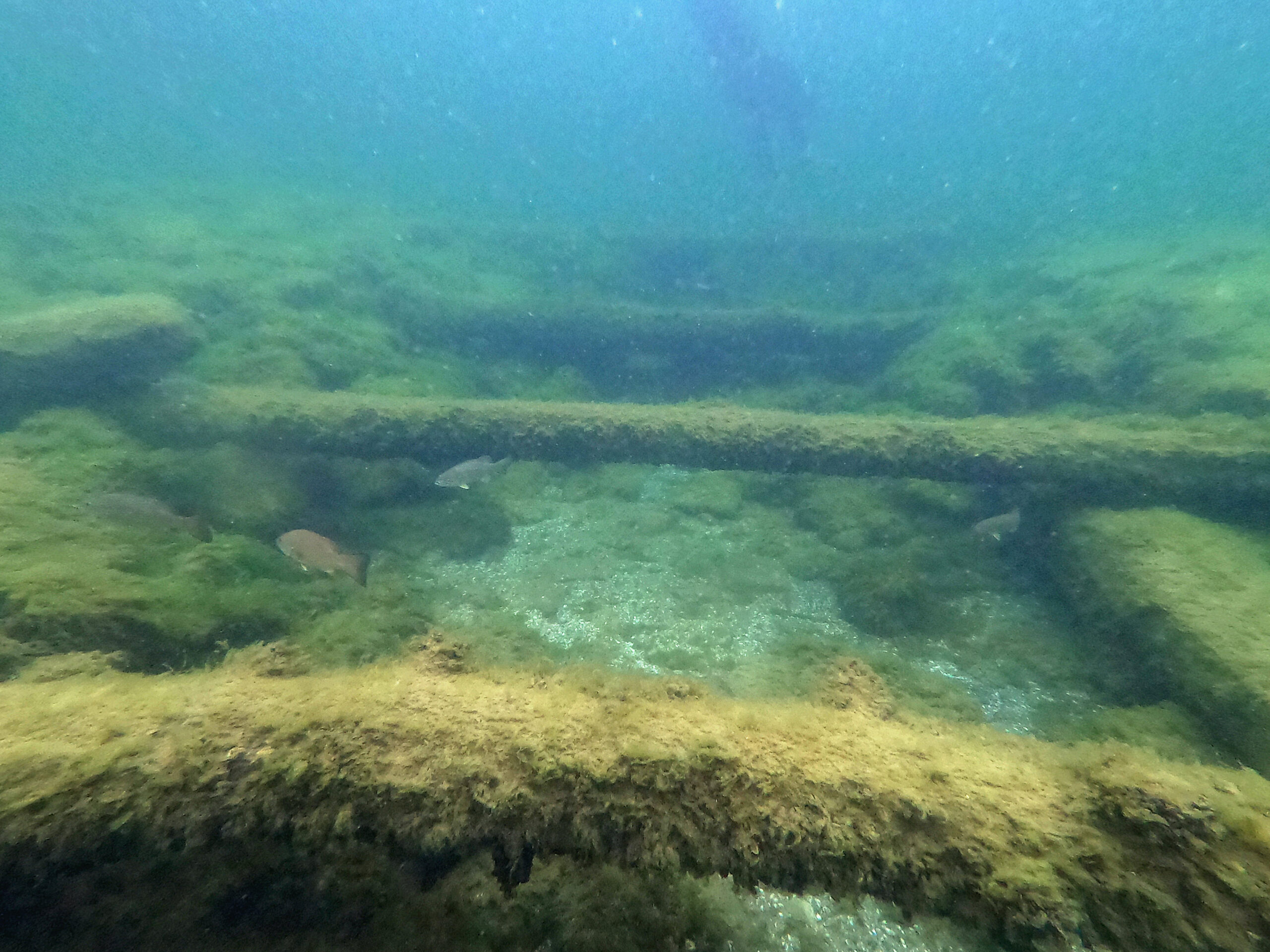

Then, thanks to metal detecting and ground-penetrating radar equipment, the team found pier remnants offshore and part of the pier that had washed up on the beach, Rosebrough said.

David Hirn, one of the Ronk descendents, “was able to sit there and touch his ancestors’ pier and know that he was at a little place intimately connected to his family,” Rosebrough told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

The importance of piers

Ronksville, Rosebrough said, likely referred to a small complex of pier-adjacent buildings like a general store, warehouse, lumber yard, boarding house, worker housing, stables, blacksmith shop, even a cheese factory.

“They were just little industrial centers and populations, maybe 20 (to) 50 to 100 people at the most,” she said.

Schooners and piers worked along Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan shoreline in the mid-to-late 1800s, exporting lumber, stone and other materials, Rosebrough said.

“These piers made Wisconsin what it is today,” she said. “This is the place where the forest was exported and sent south to Chicago to build the cities and towns in the Midwest.”

“These are the places where immigrants and colonists came ashore to carve farms out of the forest land and to establish their new lives,” she said. “This is why Wisconsin’s rural counties are farming counties for the most part. These piers made it happen.”

More ghost ports revealed

As Rosebrough and members from the Archaeology Program in the State Historic Preservation Office of the Wisconsin Historical Society were digging into Ronksville, they found other names such as “Linzville,” “Nordheim” and “Yorkville.”

“These places aren’t on the maps, either,” Rosebrough said. “We realized at that point there’s a much, much larger story that’s hiding here on our coastline and the rural areas that have mostly been overlooked.”

Using historic plat maps and coastal charts, they looked for anything resembling a pier or an old road that headed straight to the shoreline or a post office in the vicinity. They conducted aerial surveillance to see if anything was hiding under the surface.

Once they discovered something pier-esque, Rosebrough and the team began scouring historical newspapers online. They pulled genealogical records and tax records “to reconstruct histories of places that have mostly been forgotten,” Rosebrough said.

Rosebrough said there could be more than 100 of these lost pier complexes — what she called “ghost ports” — along Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan coastline.

Visiting a Door County ghost port

Rosebrough recommends checking out Newport State Park in Ellison Bay.

“Anyone who’s visited and gone to the swimming beach has without knowing it been sitting more or less right on top of the old post office and pier store,” she said.

Just offshore, visitors can kayak or canoe out, and if the water is clear enough, you should be able to see the tops of these structures, Rosebrough said. There are still pieces of pier that have washed up on the beach.

Near Baileys Harbor is one of Rosebrough’s favorite hidden gems, Toft Point State Natural Area. This ghost port you can walk to and see piles of quarry stones in the woods “waiting for schooners that are never going to come pick them up again,” Rosebrough said.

For curious investigators, Rosebrough recommends leaving alone anything you find.

“Items in the water especially don’t like to be taken out of water, especially things that have been in the water for 100 years,” she said. “They look fine when you pull them out, but they’re going to disintegrate in short order.”

It’s better to notify park staff if that’s where you happen to be, Rosebrough said.

Rosebrough and her team continue to research ghost ports as part of an effort to understand lost coastal communities. She said they’ll add histories and reports as they complete them to the Wisconsin Shipwrecks website.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.