In 1917, a Milwaukee reverend named Jesse S. Woods founded the Booker T. Washington Social and Industrial Center, named for the Black educator and founder of Tuskegee University. The center served the city’s Black residents, providing boarding, recreation and social services — while the rest of the city denied them access to those things.

This concept of a society within a society is at the center of historian Joe William Trotter’s new book “Building the Black City: The Transformation of American Life.” Trotter received his bachelor’s degree in history and education from Carthage College in Kenosha.

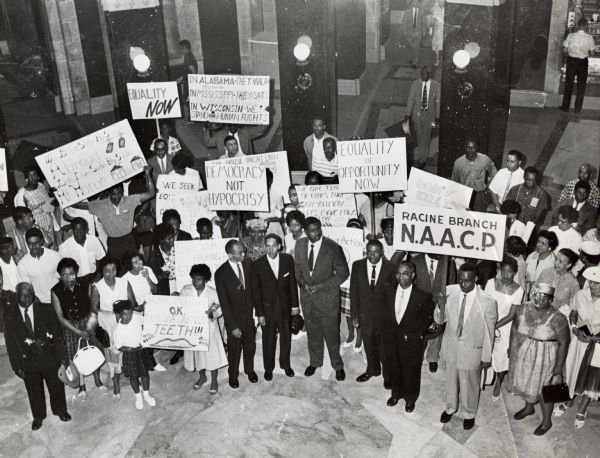

For generations, Black Americans have had to forge their own way, creating their own opportunities and places since they were denied the same rights and opportunities as white people, often by force of law.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

And as early as the 1940s, sociologists and anthropologists were acknowledging the concept of the “Black city,” Trotter told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Historically, they defined the Black city as a segregated, geographical place within a larger town or city.

“We tend to look at the Black urban experience through the lens of inequalities and victimization,” Trotter said.

But Trotter wanted to focus his book on the resourcefulness and creativity that Black people in the U.S. have used throughout centuries to build lives for themselves — without denying the reality of Black oppression.

“‘Building the Black City’ tries to revamp and redirect our understanding of Black urban life around this notion that Black people didn’t just wait for reparations to take place or for people to rectify past injustices,” Trotter said. “They went about building a city within the city to address their own needs.”

Trotter points to the Great Migration as a huge force in furthering the development of Black institutions. The influx of Black migrants to Milwaukee in the early 20th century brought Black Milwaukeeans a number of milestones: their first Black-owned community pharmacy, funeral home, weekly newspaper, and building and loan association.

“This is all about the way Black people harness their resources — meager resources — to build churches, to build businesses,” Trotter said, “and to … craft… social infrastructure (and) economic infrastructure that was designed to serve the needs of Black residents.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.