A three-year grant from the U.S. Department of Justice will allow the Wisconsin Innocence Project to look back at its past cases and reinvestigate them using recent advancements in DNA technology.

At $1.5 million, the grant is the largest in the Wisconsin Innocence Project’s History. Rachel Burg, who directs the legal clinic, said it could be a game-changer.

“DNA testing is really expensive,” Burg said, adding that the project has gotten price quotes for forensic testing ranging from $15,000 to $30,000 per case. “I don’t think people generally know how expensive it can be.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The grant will allow the Innocence Project to hire three additional full-time staff members — an investigator and two attorneys.

Each year, the project gets around 100 applications to revisit convictions. Burg hopes the grant will allow the project to fully investigate 10 to 12 cases, leading to litigation in five or six of them.

“Every single year that somebody is waiting for our assistance is a year of their life that they are missing in their communities and with their families,” Burg said.

As part of the reexamination process, the project will dedicate a special focus to past convictions of Black, Latino and Indigenous Wisconsinites.

“Wisconsin disproportionately incarcerates people of color, and we know that those disparities run from the very start of a criminal process at the stops and arrests of folks all the way through incarceration,” Burg said. “That trickles through into our wrongful conviction cases.”

When DNA testing first emerged as a method to solve crimes in the late 1980s, it was much more limited, and often required samples of blood, saliva or semen, Burg said.

New, more sensitive methods are helping scientists analyze genetic material from hair. And so-called “touch DNA” is emerging as a way to identify suspects from a small sample of sweat or skin cells that were left on an object that was handled at a crime scene.

Forensic genealogy helped exonerate brothers of Green Bay murder

Burg said the new grant will be used for forensic or investigative genealogy, a growing field that uses the DNA profiles of relatives to map out a genetic family tree to identify or exclude certain suspects. Those techniques have been gaining prominence as at-home DNA tests become more popular, increasing the availability of publicly accessible genetic information.

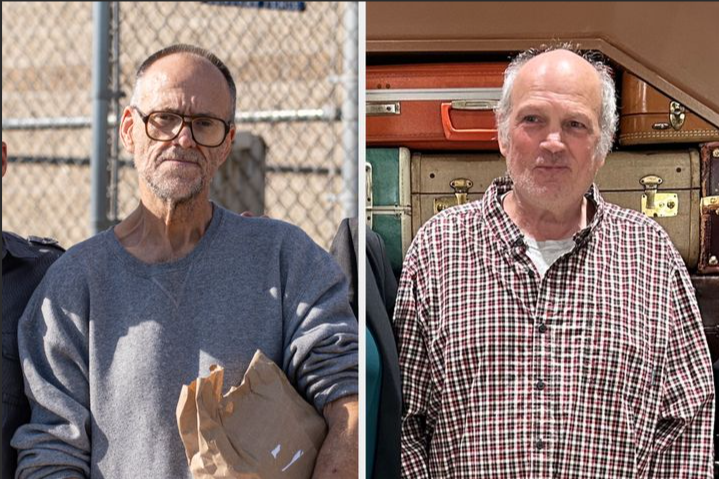

Innocence Project investigators recently used investigative genealogy to exonerate David Bintz. Bintz and his brother, Robert, were released from prison last year after spending 25 years behind bars for a 1987 Green Bay murder that they didn’t commit.

Law enforcement authorities initially theorized that the victim had been robbed, raped and killed. But by the time the case went to trial, analysis of semen found on her dress had turned up a male genetic profile that excluded both of the Bintz brothers, and prosecutors maintained that there wasn’t evidence of sexual assault.

After the brothers were convicted in 2000, Innocence Project investigators used additional testing to conclude that a semen sample belonged to the same man who left blood found near the victim, and they used forensic genealogy to narrow down the source to one of three male children of a couple from the Green Bay area.

Innocence Project investigators zeroed on William Joseph Henricks as a suspect, noting he had a history of sexual violence and was released from prison seven months before the murder.

Hendricks had died in 2000, just weeks before the Bintz brothers were convicted.

After the Wisconsin Innocence Project filed a motion to reopen the murder case, Hendricks’ brothers were excluded as suspects after Green Bay Police collected DNA from a surviving brother and from the son of his other brother, who had died.

Authorities exhumed Hendricks’ body in May of last year to collect DNA samples, and the Wisconsin’s State Crime Lab concluded there was only a 1 in 329 trillion chance the DNA connected to the crime could have belonged to anyone other than Hendricks, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

The Wisconsin Innocence Project operates as a legal clinic through the University of Wisconsin Law School. Since the project’s founding in the late 1990s, student teams have exonerated more than 30 wrongfully convicted people.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.