Researchers say people with clinical depression could be helped by a treatment involving psilocybin, the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms. Wisconsin scientists are among those conducting dozens of clinical trials worldwide on the use of the drug in treating depression. They say the evidence shows that, in combination with therapy, it shows great promise.

“It works,” said psychiatrist Charles Raison, a professor of human ecology and psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “How far (psychedelics) get into the culture, how far they get into the clinical space? That’s a mystery.”

Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide. And for some, available treatments don’t work.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“There’s a huge need,” Raison said. “The treatments we have help many people, but they definitely don’t help everybody. And as the years have passed, we’ve come to see that they really help a minority of patients get as well as they should be.”

Raison and collaborators recently assessed how many people could be eligible for the potential psilocybin treatment. They estimated that of nearly 15 million people in the U.S. with clinical depression, about 6 million could be prescribed the treatment, if it were to be approved. The researchers published their findings last month in the journal Psychedelics.

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring compound found in some species of mushrooms. When ingested, it can cause hallucinations in hours-long “trips.” The drug is illegal federally, but some research labs are able to study it.

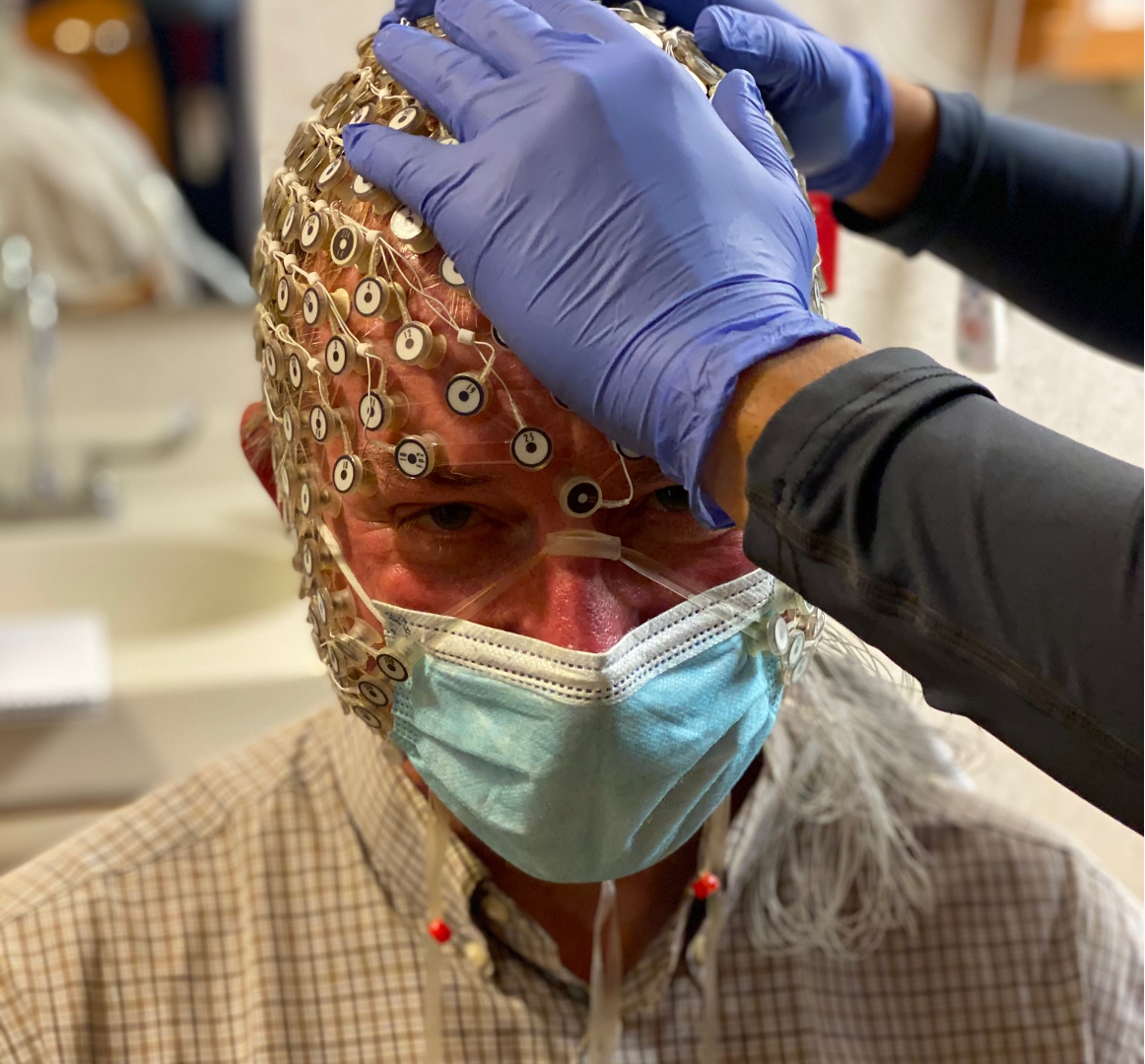

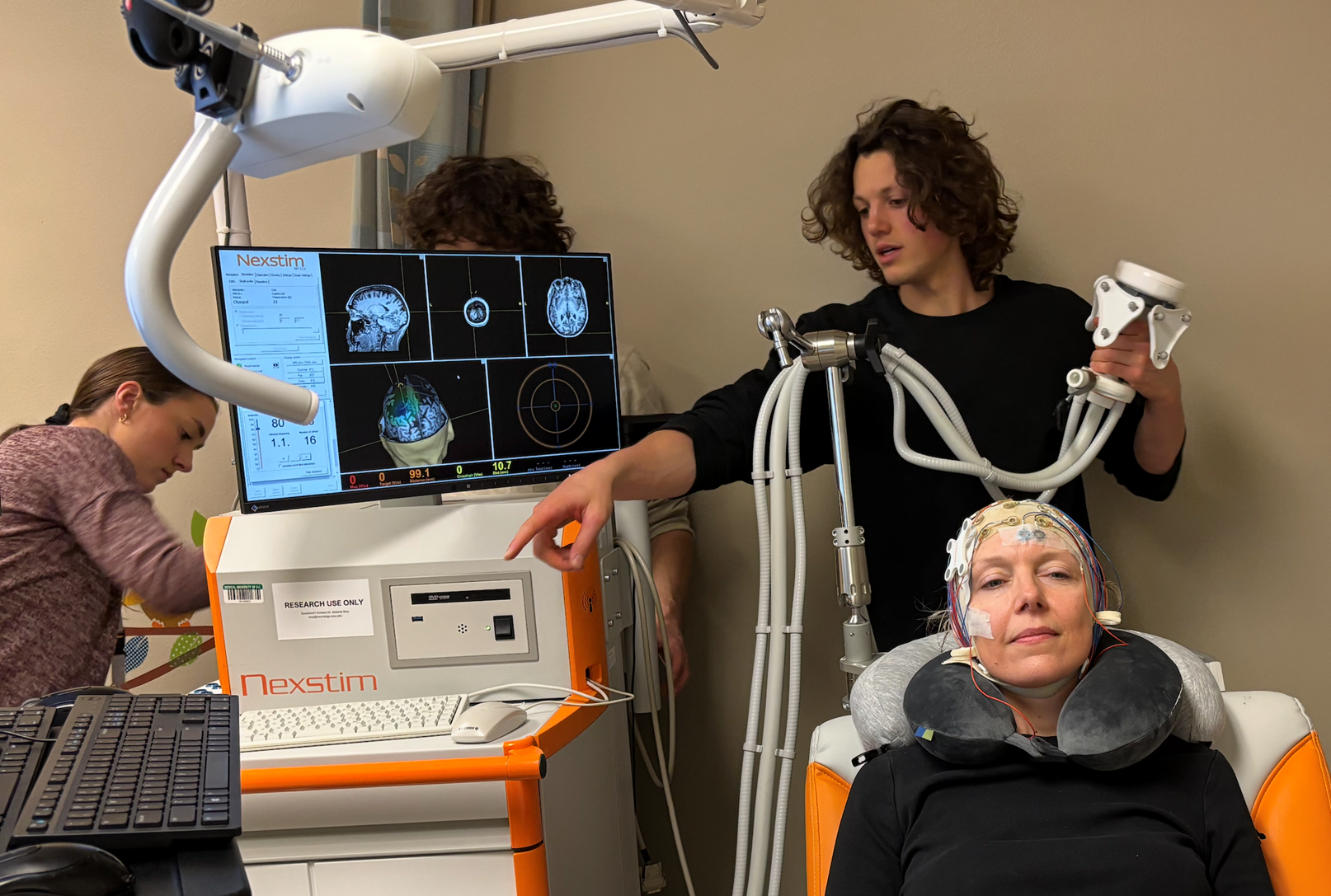

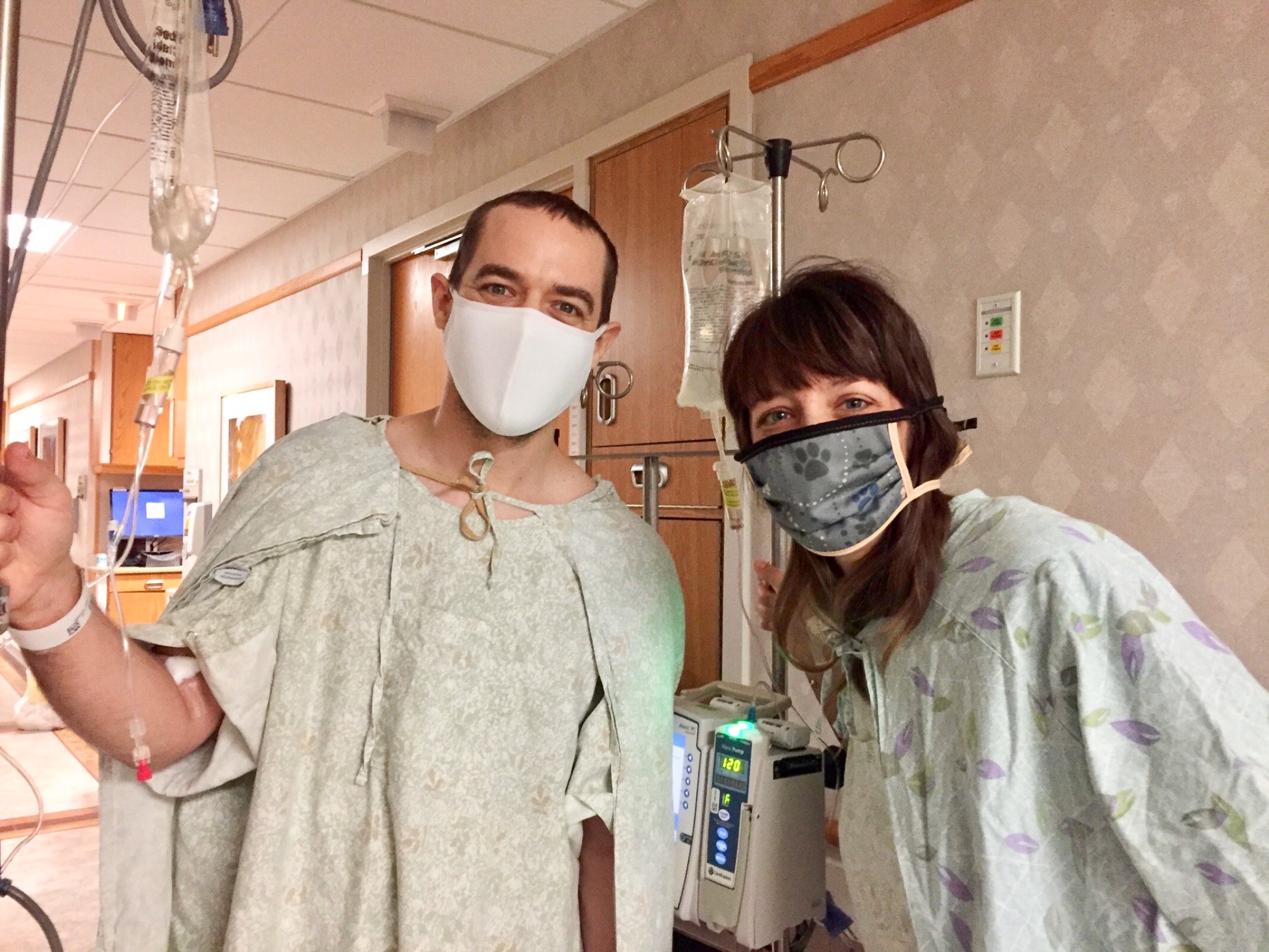

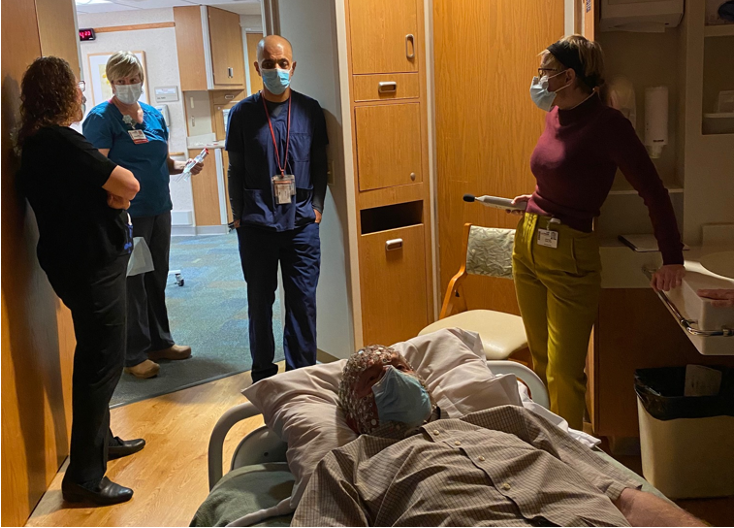

The potential treatment involves medical preparation, a therapist-supervised psilocybin “dosing day” and counseling post-trip to help the patient integrate their experience. UW-Madison conducts clinical trials with psilocybin and other psychedelics to assess their safety and efficacy in mental health treatments at its Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances.

“Most people don’t realize that Madison, Wisconsin is one of the major world centers for psychedelic research,” Raison said.

Raison helped form UW-Madison’s psychedelic program in 2015. As a physician, he was interested in studying new treatments for depression. He saw studies that found a single dose of psilocybin, with psychological support, was associated with lower depression scores three months later for people with treatment-resistant depression.

“Nobody had ever seen anything like this in mental health,” Raison said.

The FDA has granted psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression “breakthrough therapy” status, to expedite its review. Last year, a clinical trial co-led by Raison through Fitchburg’s Usona Institute found that participants had improved depression scores about six weeks after a single dose of psilocybin, with therapy.

The FDA is expected to reject or approve psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression in the coming years.

In August, the FDA rejected another highly anticipated psychedelic-assisted therapy: MDMA for PTSD. Like psilocybin-assisted therapy, MDMA-assisted therapy had received “breakthrough therapy” status. But the treatment was ultimately sent back to the lab for more testing because regulators worried the past trials weren’t rigorous enough. One reason: it’s hard to “blind” participants who are receiving a mind-altering psychedelic drug, versus a placebo.

Raison and collaborators conducted both conservative and optimistic estimates of patient eligibility for psilocybin-assisted therapy, based on exclusion criteria from psilocybin trials. For example, trials typically exclude patients who have a psychotic or manic disorder, cardiovascular risks and recent suicide attempts, because psilocybin could worsen their conditions.

“Let’s say you had a heart attack two weeks before. In our study, you could not come in,” Raison said. “And in the real world, we probably wouldn’t let you in either, because psilocybin increases heart rate and blood pressure.”

The researchers’ conservative estimate, based on the clinical trial criteria, found that 24 percent of U.S. patients with depression, or 2.2 million people, were eligible. But when a drug gets approved and goes to market, physicians don’t prescribe it strictly based on the trial criteria, Raison said. They still would avoid giving it to patients with cardiovascular risk, for example, but conditions like alcohol use disorder wouldn’t necessarily exclude the patient anymore.

“The patient groups that are brought into a trial…tend to have less problems in their life than most people who really struggle with depression,” Raison said.

The analysis suggests that perhaps more realistic estimates of the eligible populations ranged from 5.1 million to 5.6 million people with clinical depression.

Analyses like these are important because they illustrate the need for new treatments, Raison said.

“These treatments might help a whole bunch of people,” Raison said.

However, just because millions of patients could be eligible, that doesn’t mean the demand will actually be that high.

Raison and his collaborators noted that many factors, including coverage decisions by private health insurers and Medicaid, as well as state regulations, could lower the number of people who access the potential treatment.

And psilocybin-assisted therapy could be cost prohibitive. Therapy, which many researchers say is key to psilocybin’s its treatment potential, is expensive. A 2023 study estimated the treatment will cost upwards of $8,000. Currently available depression therapies can also cost thousands of dollars, but may be covered by insurance.

Psychedelics aren’t perfect, Raison said.

“For most people, psilocybin, probably all psychedelics, are not going to be eternal cures,” Raison said.

It’s possible state regulators will allow psilocybin use before the FDA decides to approve or reject it. In 2022, Colorado voters decided to decriminalize magic mushrooms, and the state is working on regulations to allow them in “healing centers” in 2025. In Oregon, people can take psilocybin with state-licensed facilitators. In 2023, Wisconsin lawmakers tried to pass a bipartisan bill to help fund psilocybin research for PTSD treatment.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.