The Logan Museum of Anthropology at Beloit College is planning to cover up part of an exhibit in response to new federal rules governing how museums should handle objects sacred to Native Americans.

The updates to the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, which took effect Jan. 12, aim to give more authority to tribes by requiring federally-funded institutions to get prior consent before displaying or conducting research on human remains and culturally significant items.

That includes anything classified as a “funerary object,” meaning something that was placed with someone for burial.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As a result of the changes, staff at Beloit’s Logan Museum have ordered materials so they can cover up the second story of a visible storage display, in which hundreds of objects are encased in glass.

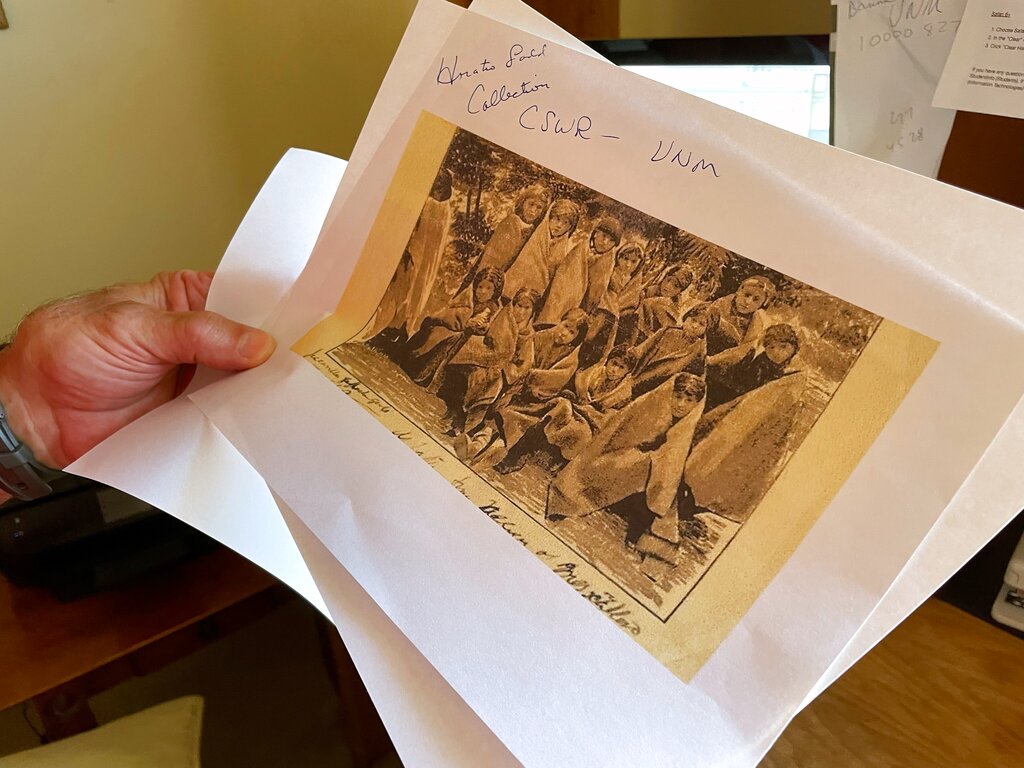

That’s because part of that display includes ceramic bowls that were associated with Native American burials, the museum’s Executive Director Nicolette Meister said. Those items were excavated in the 1920s and 30s from the American Southwest, Meister said.

The museum is also evaluating whether or not to include a Plains Indian feathered headdress as part of a display planned for February on cultural appropriation versus appreciation, Meister said.

“What’s challenging for a lot of institutions is identifying specifically what items fall under cultural items as defined by the law,” Meister said. “We want to err on the side of not making any assumptions. And we’re going to not display it until we have permission to do otherwise.”

A dozen Wisconsin museums, universities have remains from Native Americans

Beloit’s Logan Museum is among a dozen museums and universities in Wisconsin that possess human remains from Native Americans, according to a National Park Service database.

Federal data indicates Beloit’s collection includes remains from more than 100 people. Those remains are not exhibited and are instead kept in secure storage, Meister said.

“We have had a policy for the past four years of prohibiting any teaching, research learning with any human remains — not just human remains of Native American ancestry,” Meister said. “We believe very strongly that individuals should consent to have their remains be used for those purposes.”

The Milwaukee Public Museum has the largest collection of Native American remains in Wisconsin, which includes remains from at least 1,600 individuals, according to the federal database. None of those remains are used for research or display, a spokesperson said.

Under federal regulations, remains are counted as belonging to a “minimum number of individuals,” and an individual’s remains could include anything from a full skeleton to fragments that are mixed with soil.

Staff at the Milwaukee Public Museum are in the process of evaluating how changes to NAGPRA might affect culturally significant objects at current exhibits, according to written statement from a spokesperson.

“Thanks to the museum’s ongoing consultation work with tribes, the new regulations will have a relatively small impact on MPM’s exhibits compared to other museums who have closed entire galleries,” according to the statement. “MPM is thoughtfully reviewing the Native American cultural heritage items currently on display, and in the coming weeks, will remove items from view or cover exhibits that do not comply with the latest NAGPRA regulations.”

President George H. W. Bush signed NAGPRA into law more than three decades ago. Its goal was to prevent grave looting and to pressure organizations that receive federal funding to return ancestral remains to Indigenous peoples.

But, over time, the law has faced criticism over delays in repatriation. Close to half of more than 200,000 Native American remains across the country have not yet been made available for return, according to a database from ProPublica.

The latest updates to NAGPRA aim to accelerate the process by requiring museums to consult with tribes and to update their inventories within five years.

They also could close a loophole that critics say researchers and collectors were able to use to get around NAGPRA regulations. The new rules eliminate the option to list human remains as “culturally unidentifiable,” and instead expand the criteria that institutions should use when identifying communities that are connected to the remains.

Oshkosh Public Museum will hire consultant focused on repatriation

At the Oshkosh Public Museum, the latest NAGPRA updates won’t result in changes to current or planned exhibits, said Director Sarah Phillips.

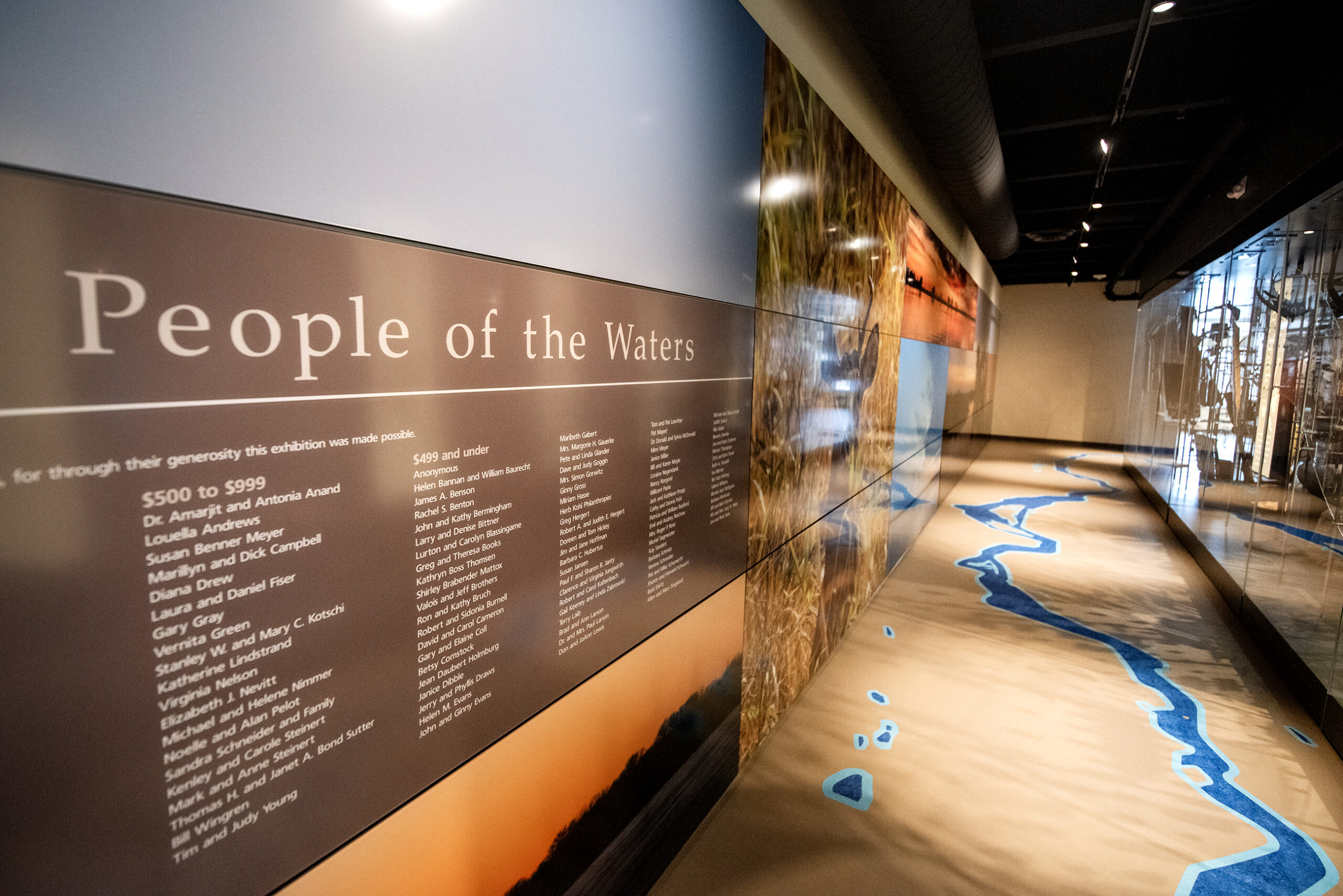

“We’re in pretty good shape, knowing and feeling very confident that the tribes support everything that’s on exhibit and how it’s been interpreted,” Phillips said, adding that the museum consulted with tribes about displays about Native life, such as its People of the Waters exhibit.

The museum’s latest inventory found that the Oshkosh Public Museum had remains from more than 50 people, Phillips said. Those remains are kept in storage and aren’t exhibited or researched.

Last year, the Oshkosh Public Museum Board approved funding for a repatriation consultant who will start work this spring, and Phillips said she’s hopeful the latest NAGPRA rules will speed up the process.

“It’s an honor for the museum to know that we’re holding those (remains) in safekeeping,” Phillips said. “But I’m very curious to know how many people we can send home.”

Across the country, the NAGPRA changes have prompted major museums, including the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan and the Field Museum in Chicago, to temporarily close or cover up exhibits.

But at the Neville Public Museum of Brown County, which is located in Green Bay, adjustments to current exhibits will not be necessary, said Executive Director Beth Kowalski.

“I’m proud to say that I’ve worked at institutions that have upheld and done their diligence,” Kowalski said. “I hope that much larger institutions really make a concerted effort to help repatriate as much as they possibly can.”

Federal data shows the Neville has remains from more than 50 Native Americans, but those remains are not displayed and would not be used for research without prior permission, the director said.

Kowalski said she’s optimistic that expanded criteria under the latest NAGPRA rules will result in more remains and other sacred items being returned to descendants.

“It’s exciting, because now we can go look at more geography and location,” Kowalski said of determining ancestry. “It allows us now to reach out to tribes that would have been in that geographic place, and hopefully then be able to have them make decisions about how do we return their ancestors to them.”

How other Wisconsin institutions responded

The Board of Curators for the Wisconsin Historical Society approved amendments to the agency’s collection policy earlier this year to ensure compliance with NAGPRA updates, a spokesperson said.

“The Wisconsin Historical Society has been working diligently since NAGPRA passed in 1990 to ensure full compliance with the regulations,” the society said in a statement. “We work closely, responsively, and in good faith with interested Tribes and Nations in Wisconsin and elsewhere on this important, collaborative work. We have staff specifically dedicated to this work and over the years we have made special efforts, such as applying for and receiving multiple documentation and repatriation grants through the National NAGPRA office in Washington, D.C., to assist with this effort. It continues to be a high priority for the agency. “

The Madison-based society holds Wisconsin’s second-largest collection of Indigenous remains, according to federal data. The museum has remains from more than 200 people in its collection, according to ProPublica.

The society doesn’t display human remains at any of its locations, and it only allows access to them when needed to comply with NAGPRA or state law, according to a spokesperson.

Two Wisconsin institutions that hold human remains listed in a federal inventory — the Kenosha Public Museum and the Washington County Historical Society — did not respond to requests for comment

Other Wisconsin institutions with Native remains sent the following statements in response to questions about how they’re affected by the rules:

Lawrence University: “No modifications made because Lawrence has already inventoried its holdings and has repatriated all culturally identifiable material. Lawrence has also already notified the Wisconsin Inter-tribal Repatriation Committee that it is interested in repatriating any culturally unidentified material.”

University of Wisconsin-La Crosse: “UW-La Crosse has been reviewing the revised regulations for repatriating ancestral remains and cultural items and is committed to complying with the latest guidance. We are grateful for our strong relationships with our Tribal, agency and institutional partners. And we look forward to further consultation with them as we continue this important work.”

University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh: “For the last several years, in consultation with Tribal Nations, all campuses of the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh have diligently worked on NAGPRA compliance issues. While UWO has already taken proactive steps to regularly consult with Tribal Nations and make sure best practices are in effect, we will continue to consult with Tribes to ensure that we are responding to the new regulations appropriately and as expeditiously as possible.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Anthropology Museum Director and Campus NAGPRA Coordinator Liz Leith: “The university is already in compliance with the recently announced NAGPRA revisions. UW–Madison does not have human remains or cultural items on exhibit, and access to and research on human remains and cultural items is already restricted, pending approval through consultation. My colleagues and I in the Department of Anthropology have been consulting with the Wisconsin Intertribal Repatriation Committee since the mid-2000s. UW-Madison deeply values and prioritizes consultation as a standard practice in relation to human remains and cultural items present on campus. Through these consultations, we have successfully repatriated most of the remains and cultural items that had once been on campus, and we will continue our work to maintain a strong shared future with Wisconsin tribes.”

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee: “UW-Milwaukee is committed to complying with the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act and is aware of the new regulations. The University continues to work closely with tribal nations to ensure compliance with both the letter and spirit of the law.”

Editor’s note: The story was updated to better characterize museums’ collections of Native American remains.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.