Moments before an assembly to pray for peace in Ukraine, Principal Anna Cirilli bounces from conversation to conversation inside St. Nicholas Cathedral School in Chicago.

She first speaks with a television news reporter and calls the gathering a way to “look evil in the eye and show them that they’re not winning.”

The school has welcomed more than 140 children who have fled Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Over the last two years, Cirilli has done more news interviews than she can remember. She wants others to see, hear and feel the war’s lasting effects on children.

The Wisconsin native also cherishes how St. Nicholas is helping students resettle.

“All the students that have come are successful here,” she said in the interview with the TV reporter. “They’re happy. They’re safe.”

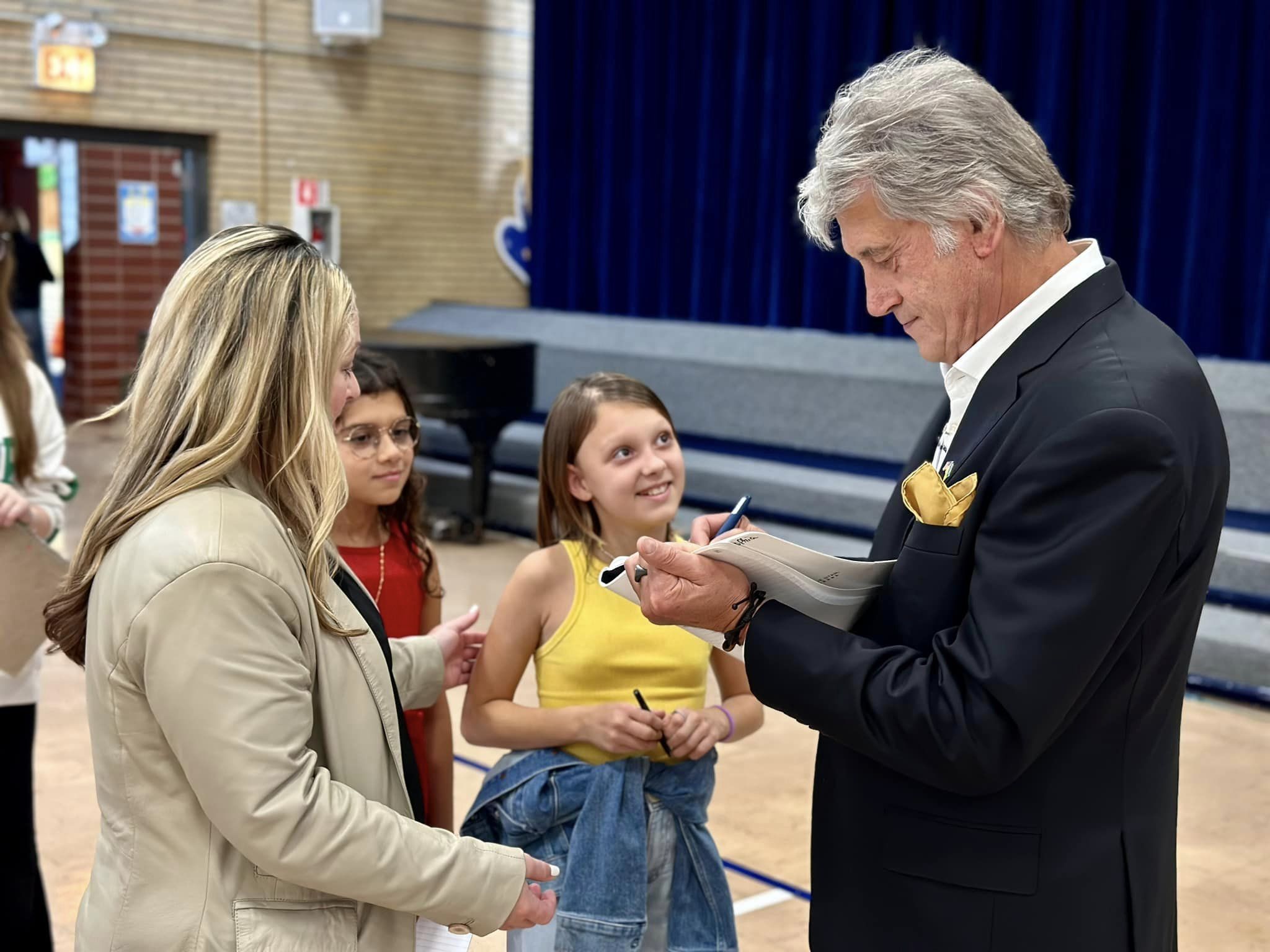

Cirilli next talks to several high-profile guests: elected officials, education leaders in the city and representatives from community groups. The school assembly’s guest list includes U.S. Rep. Mike Quigley, a co-chair of the Congressional Ukraine Caucus, and Adrienne Scherenzel, executive director of Chicago Bulls Charities.

Between the conversations, Cirilli talks to students. She answers questions and helps put the final touches on the assembly. Some students hold sunflowers, a symbol of peace in Ukraine.

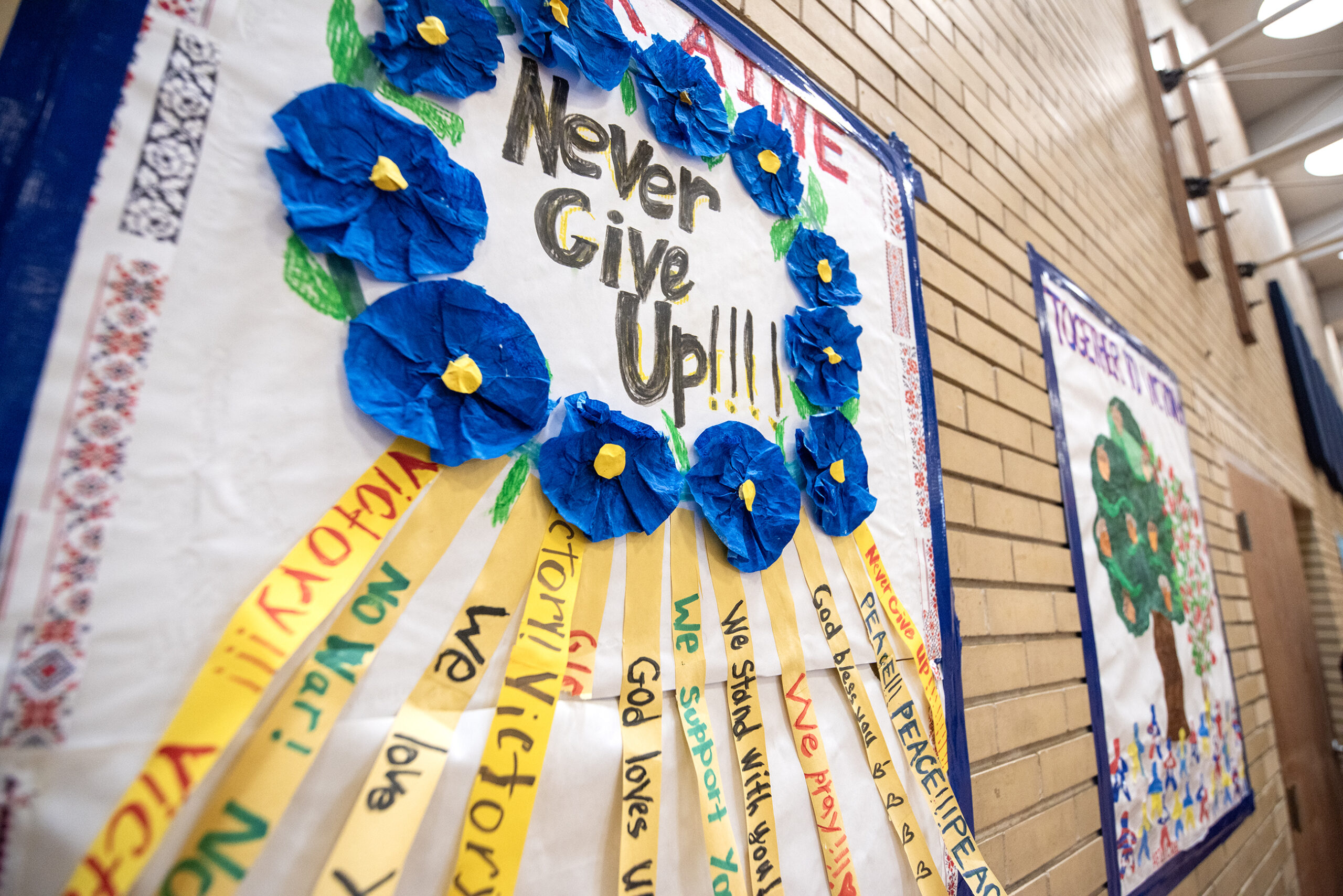

Life at St. Nicholas now means oscillating attention from a war that has killed tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops and civilians to routine classwork like math and reading. While the students at St. Nicholas fled the war, the trauma they endure remains present. The gym where children play volleyball and basketball is covered with posters of peace signs.

Leading the school, Cirilli says St. Nicholas desperately needs funding for scholarships so kids can afford their tuition. She feels under pressure to fundraise, network and raise awareness amid managing the trauma from a war thousands of miles away. Last year, she lost feeling in her hand and went to the emergency room. Stress had caused a pinched nerve, she said.

“It has been a tough two years,” Cirilli said recently. “The moments of these difficult conversations eventually just catch up with you.”

At the school assembly, each attendee receives a yellow candle. Then, Cirilli pulls out a lighter to start a chain of candles lighting candles. Chattering students quiet down as the room illuminates. The crowd silently prays for hope in Ukraine as Cirilli’s spark ignites and unites the room.

Career in education started in Superior

Cirilli grew up in Superior. She spent early years running around courtrooms because her father, James, was a lawyer. His father, Arthur Cirilli, also served as a Wisconsin state senator for more than five years before Gov. Patrick Lucey appointed him to be a Douglas County judge in 1972.

In an interview from his home in Superior, James said his daughter takes after her grandfather in many ways.

“She knows how to get things done,” he said. “She works really well with people, and she can be very influential.”

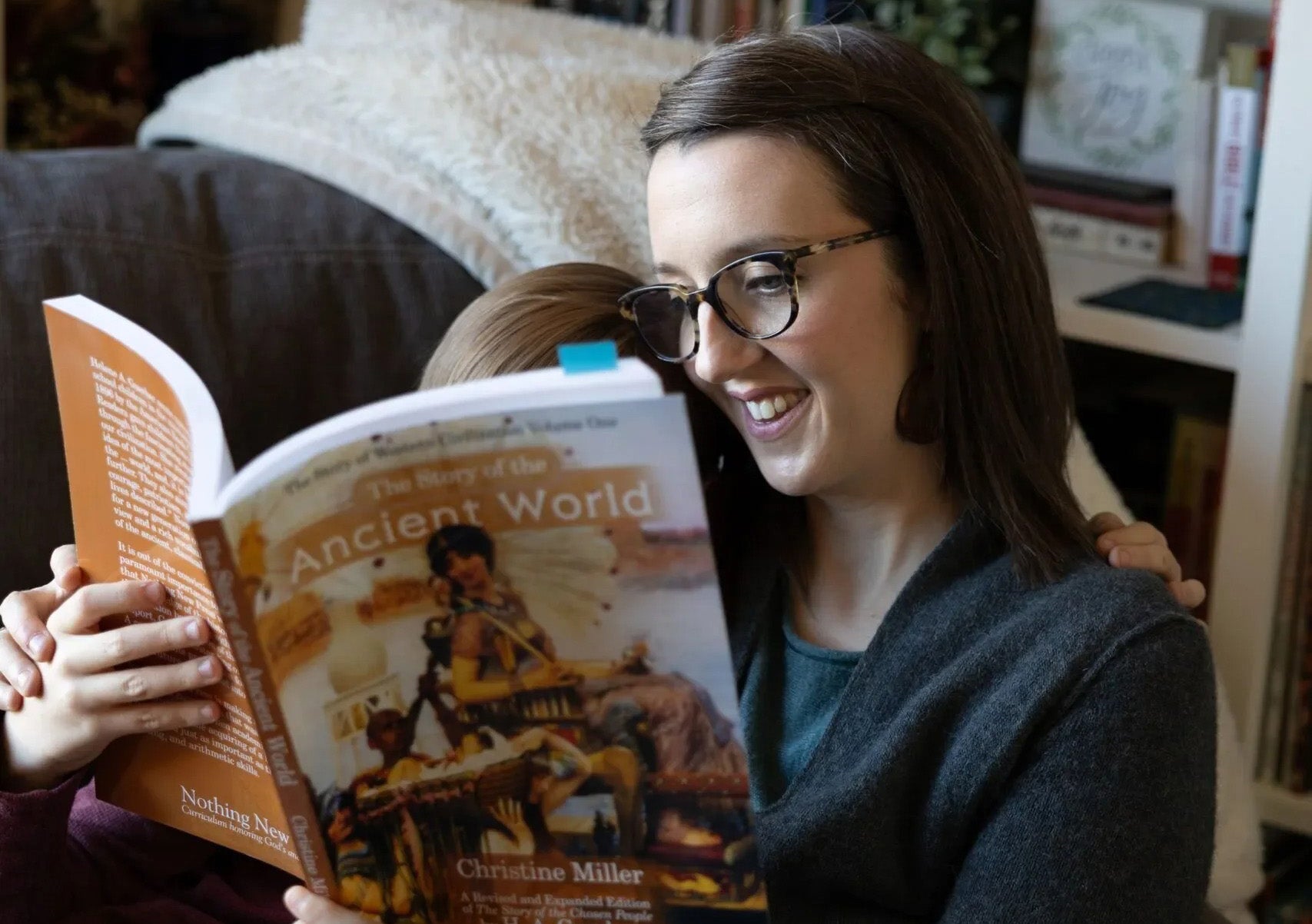

Cirilli stayed out of politics, though. Her heart belonged in education. As a kid, she asked permission to dig through the garbage to find discarded teacher’s manuals and children’s books, she said. She used the books to set up a pretend class in her bedroom. Friends, siblings and cousins became her students.

“I don’t know if that’s normal,” she said with a laugh.

Cirilli enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1994 and was among the first class of an education fellows program. After college, she became a teacher on the south side of Chicago for about 12 years. Then, she felt a need to explore and moved to Italy, where she taught English for a few years.

When she returned to Chicago, Cirilli worked at a restaurant and met a board member from the Big Shoulders Fund, a nonprofit charity that supports under-resourced schools. That person then introduced Cirilli to Josh Hale, the charity’s president and CEO.

“Within about 10 minutes of talking to her about her passion, I called our chief schools officer and said, ‘You’ve got to get over here and meet Anna,’” Hale recalled. “We’ve got a phenomenal person and human being, but also, I could tell, a great leader.”

Cirilli started in 2015 as principal of St. Nicholas Cathedral School, where about 90 percent of students are now Ukrainian or Ukrainian-American. St. Nicholas is part of a Chicago neighborhood known as Ukrainian Village. The school was built in 1936 “by Ukrainians for Ukrainians” and expanded following World War II, Cirilli said.

Hale said he appreciates how Cirilli organizes supply drives to provide families with clothes, toiletries and other needs. Most students at the school come from families with lower incomes and less access to education.

For her work at St. Nicholas, the Wisconsin Alumni Association is considering Cirilli for its Luminary Award, which recognizes leadership and service from UW-Madison alumni.

New students and challenges following invasion

Sitting in a school office at St. Nicholas, Cirilli’s voice starts to break recalling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the arrival of families fleeing the war.

As the leaders of Catholic schools in Chicago continued managing one crisis — effects from the COVID-19 pandemic — they realized another crisis loomed. Russian troops were assembling near borders with Ukraine.

As the invasion began, Cirilli talked with school and church leaders. They agreed to meet at a church to pray for peace and hope. Families arrived, too. Most everyone at St. Nicholas had relatives in Ukraine, Cirilli said. They were shaken.

A week later, a 13-year-old former student, Dmytro, rang the school’s doorbell. After his time at St. Nicholas, he went to Ukraine to study music. But his mom worried he would be asked to fight in the war. Dmytro and his mom arrived at the school with their suitcases unsure where else they could go, Cirilli later told The Washington Post.

The doorbell kept ringing at St. Nicholas. Nearly half of the school’s current enrollment arrived from Ukraine within the last two years. Cirilli said students affected by the war require more care than other students, adding to the challenges for a staff of fewer than 30 people.

Exposure to trauma can affect students’ ability to remember and focus, which can reduce their academic performance and school engagement, according to the American Psychological Association. At St. Nicholas, some children have produced drawings that are exclusively in black or depict tanks and other images of war.

St. Nicholas experienced a spike in donations to help support students and their families in the months after Russia’s invasion. But Cirilli said those donations have since slowed down, reducing the school’s ability to cover tuition for students who cannot afford the costs. She would rather be spending time with students and teachers, but she needs to court donors, too.

St. Nicholas is struggling to make ends meet, said Irka Tkaczuk, the school’s board president.

“We’ve always been a poor school,” said Tkaczuk, an alumna of St. Nicholas herself.

‘How else can we help?’

Nataliia Sydorenko fled Ukraine in 2022, moved to Chicago where relatives live and enrolled her two children at St. Nicholas. They are now in the third and eighth grades. Sydorenko is grateful to find a place where her family can feel safe and learn English, too.

“For me and for my kids, it’s like the second family,” she said of the school.

Cirilli said students must feel safe before they can be academically successful. When refugees arrive at the school, their trauma shows up in schoolwork, conversations and behavior.

Greg Richmond, the superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Chicago, recently asked Cirilli to speak with a group of principals in Chicago about running schools with large populations of refugees or migrants. Chicago has received many from across the world.

“Her commitment and care for the students and families is just so powerful and so clear to people,” he said. “It’s all the more impressive when this school, she and the teachers and staff have been handed this crisis unexpectedly.”

Like Cirilli, Richmond is a Wisconsin native and UW-Madison alum. He said that while Chicago might seem like a faraway and mysterious city, the challenges for its schools and the needs for its students aren’t that different from schools and students in Wisconsin.

“The support for this school from this community has been very impressive,” he said. “If the same thing happened on the east side of Madison, the support there would be very impressive. That’s a bright spot in a sometimes-gloomy world.”

Cirilli and St. Nicholas have drawn support from Wisconsin, too. The Door County Candle Company held a fundraiser for the school’s scholarship program. The company also provided candles for gift bags at the school’s recent assembly.

Christiana Trapani is the candle company’s owner. Her parents were married at St. Nicholas Church in Chicago. Her grandparents were strong supporters of the church and school.

To date, the Door County Candle Company has raised more than $1 million for a nonprofit that delivers medical supplies to war-town parts of Ukraine and helps families evacuate. Trapani’s aunt remains in Ukraine and keeps the family informed on the war.

“It always hits me,” Trapani said. “What else can we do? How else can we help?”

‘Slava Ukraini!’

At a dinner last fall with Viktor Yushchenko, the former president of Ukraine, Hale remembers Yushchenko speaking about his desire to visit St. Nicholas because he heard about a woman at the school doing more than anyone in the area to help displaced Ukrainians.

Yushchenko was referring, of course, to Cirilli.

“He then went on for another 10 minutes about the students he had met, the families he had met, the teachers and about Anna’s leadership that made it possible,” recalled Hale, head of the Big Shoulders Fund. “It was wonderful.”

Students had welcomed Yushchenko to the school with bread, sunflowers and traditional Ukrainian songs. His wife, a Chicago native, later praised the school in a Facebook post.

“The children were remarkable,” wrote former First Lady Kateryna Yushchenko. “The administrators and teachers we met are incredibly dedicated.”

Months later in the same gym where students met the Yushchenkos, Cirilli is thanking her teachers for their hard work and her students for organizing a school assembly recognizing the two-year anniversary of the invasion.

She asks students born in Ukraine to raise their hands. Then, she spots one student from Ukraine with their hand down and encourages them to hold it high.

To end the assembly, she reiterates that evil would not win. Then she yells, “Slava Ukraini!” — a national salute and battle cry meaning, “Glory to Ukraine.”

With their sunflowers and candles, the students let out their own high-pitched roar: “Heroyam Slava!” Glory to the heroes.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.