For the first time in a decade, the American Academy of Pediatrics released updated recommendations on how pediatricians and caregivers can encourage early childhood literacy, with a Wisconsin doctor working on the effort.

Dr. Dipesh Navsaria, professor of pediatrics and human development and family studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, helped write the new literacy promotion policy statement and accompanying technical report. He told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” what parents and healthcare professionals should know.

Navsaria emphasized the benefits of reading with a child, which he said are more substantial than any virtual or high-tech learning tools.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“There is no app to replace your lap,” he said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics statement also highlights the work of Reach Out and Read, a national organization that encourages healthcare professionals to make reading a part of early childhood checkups. Its work includes donating books for pediatricians to “prescribe” to young patients. The New York Times recently recognized Reach Out and Read with the newspaper’s 2024 Holiday Impact Prize.

Navsaria is the founding medical director of Reach Out and Read’s Wisconsin affiliate and host of the national organization’s podcast. He said the organization is more than a literacy program.

“Reach Out and Read is actually secretly a parenting support program,” he said.

Wisconsin Today talked with Dr. Navsaria about the new early childhood literacy recommendations, the roles that pediatricians and parents play, and the benefits of the Reach Out and Read program.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: When we read to our kids in an animated, active way, does it make a difference? Does that passion rub off?

Dr. Dipesh Navsaria: Folks who have been around people who read to young children, we automatically absorb a lot of these things: making different voices or asking the child questions about what they can find on the page, and doing this back-and-forth.

The fancy term for this is something called dialogic reading. But if you’ve not been exposed to this, you may think that a young child is supposed to sit quietly and just be read to, and whatever’s on the page is exactly what you do. And I think you and I both know that that doesn’t work so well with a naturally short attention span of a squirmy 15-month-old, for example.

KAK: The new recommendations include reading to children starting at birth, rather than waiting until they’re 6 months old as recommended previously. What can infants absorb in these interactions so early on?

DN: When you do good shared reading all the way from the early days of life, you’re contributing not just to early literacy, but also to early relational health, which is just as important. When a child is in your lap and they’re hearing your voice, they’re hearing the cadence of sentences, they’re hearing the love, they’re feeling your touch. You’re doing something together. All of these play into that child and really feed their development in ways that absolutely nothing else can.

We need to remember: There is no toy, no video, no app that will drive development forward on its own. It’s nurturing, caring, responsive interactions with others.

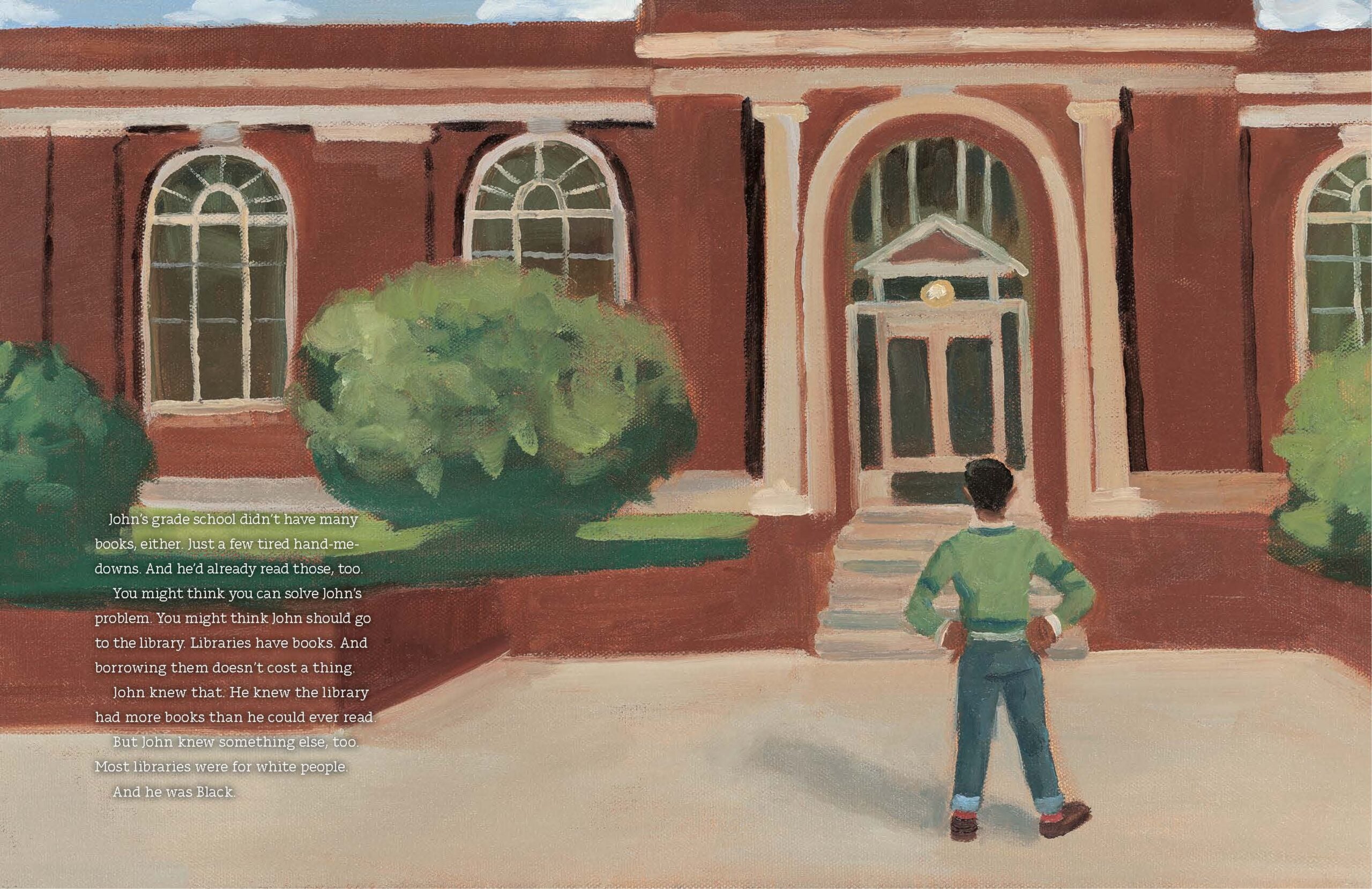

KAK: The new recommendations expressly say that the print books are better than digital books for young children. Why is that?

DN: We find that the turning of paper pages, and the fact that there’s not other distractions in a paper book that can exist on electronic devices, make them a better choice.

Now I want to be really clear about something: If a family says to me, “We’re out and about with young kids the whole day, and if we have some downtime, we’re pulling out an iPad and we’re looking at one of the 40 picture books that I have loaded on that iPad.” … Of course, that’s absolutely fine. But if you have a choice, I would say, yes, go for the traditional paper books rather than ebooks.

KAK: What do you think of reading the same book to a child over and over, if that child asks for it?

DN: That child is telling you a couple of things. One: They love the book, something about it. And with a young child, we don’t always know as adults why a particular book appeals to a particular child. We do know that the more beautifully written, the more amazingly illustrated, the more narrative depth and complexity that there is there, the greater the chance that it will connect with a child on some level. So, we need to keep that in mind.

And two: They’re saying, “I love it when you read this book aloud with me and share it with me. And I want to do that.” It’s not just about the book, it’s also about you.

KAK: How can pediatricians and other healthcare professionals help new parents and caregivers become more confident in reading with their children?

DN: Parents — sometimes with lower educational attainment — think, “I’m the wrong person to be teaching my child. I didn’t do so well in school myself. I’m going to mess them up. Maybe this learning DVD is better for them.” And of course, it isn’t. The training we do with families is to ask about shared reading, reinforce what they’re doing right, and if they mention that their child doesn’t seem to enjoy reading, take out the book we just gave them and ask them to read a few pages and offer some quick tips. Do some modeling, some coaching.

KAK: How receptive are pediatricians to adding this additional responsibility in their appointments?

DN: When I do talks for trainees, we play a sample recording of a Reach Out and Read visit. Then we talk through all the things we learned about the child’s development: about family structure, what they do together, relational health, etc. After we’ve made this long list of all the things we’ve learned that we’re supposed to be doing anyways, I point out that that entire video lasted three minutes.

It’s a really good use of three minutes. It occurs when the clinician walks in with the book in their hand, gives it directly to that child, and watches their response. Do they toddle over to their parent and hold it out in that “read to me” gesture? Do they start turning pages? Do they start saying words? You learn so much in those few moments by doing skillful and intentional observation that honestly, I learned more from that book in most checkups than I do from my stethoscope.