When James Lenfestey was growing up in De Pere, his mother took him and his siblings to a woman in town who painted portraits.

One sister’s portrait showed her as a princess, and Lenfestey said she remained a princess her whole life. Another sister’s painting showed her dancing. And to this day, he said that sister — who is now 82 — remains an incredible physical therapist, hiker, skier and dancer.

“She’s a complete physical being,” he said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

When the painter sat Lenfestey in a chair, she said, “That boy needs a book in his hands.” He was 3 years old.

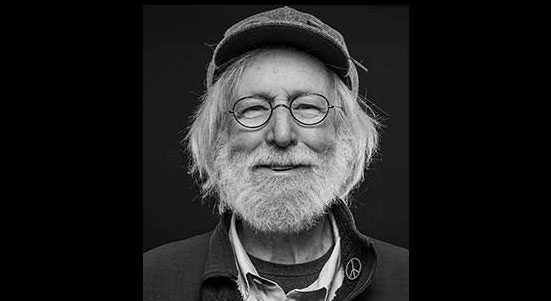

The painter was on to something. Lenfestey grew up to be an avid reader and eventually became a writer himself. He has published seven collections of poetry in his seven decades of life, including the forthcoming “Time Remaining: Body Odes, Praise Songs, Oddities, Amazements.”

Lenfestey spoke with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about his new book, growing up in Wisconsin and the enduring power of art.

“What persists through all of this? The answer is art. It gives us hope, because art is persistent.”

James Lenfestey

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: When did you start to see yourself as a poet after that experience with the painter?

James Lenfestey: I went to Dartmouth College. They had one class in creative writing, and I took it. Now we all have (Master of Fine Arts) programs everywhere. I went to the graduate school at the (University of Wisconsin-Madison) for a master’s — loved it, by the way. And there was one class in creative writing. I took it.

It’s a fascination with the sound of words, the roots of words, the long vowels which entrance us. Robert Bly discussed “the seven holy vowels,” and you can hear them in Yeats. We “will arise and go now and go to Innisfree.” Hear those vowels just roll over the horizon. So those are some of the things I’ve always been entranced by, the pieces and language and how it goes together.

What persists through all of this? The answer is art. It gives us hope, because art is persistent.

KAK: The first section of your new book is odes about various parts of the body. The first one is an ode to your ankle, which you wrote after you seriously injured it. Can you tell us about that poem and the ode to the ankle?

JL: I skidded out of my socks on a bike rack and tore the daylights out of my ankle. And that torqued a couple of tendons loose. They were frolicking around on my ankle, and I was lying in bed wondering where this would go, and I wrote “Ode to the Ankle” and the rest is history.

The ode gates opened. I looked at my left hand: “Oh, what’s that story?” And then what about this belly of mine or yours? And on and on. I walked into a restaurant alone on the way to the theater (one day), and what did I see? Jaws moving up and down. “Story of Jaws” became a long, long poem. And of course, the heart.

KAK: Does your journalist background help you be a better poet?

JL: When I left a day at the editorial board of the Star Tribune (in Minnesota), my head was hot. When I leave a day writing poetry or essays, my hands are hot. The difference is complete. Poetry comes from the body. It comes from inside you. It comes from mysterious sources, the mystery of your birth and the mystery of your death and everything in between. And so you find yourself creating metaphors that try to capture what you don’t know. I love that kind of (journalistic) work, but poetry is from a different place. It’s an entirely different thing, but it is entangled in the roots of words.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.