The Green Bay Correctional Institution would be closed and the Waupun Correctional Institution converted into a new “vocational village” to train incarcerated people for jobs under a set of “sweeping reforms” Gov. Tony Evers will propose in his new budget.

Some nonviolent offenders would also have expanded opportunities to earn earlier release through completing job training and substance use programs under the governor’s proposal.

Evers and Department of Corrections Secretary Jared Hoy described the plan as a “domino series” of changes to facilities across the state, with each step contingent on the others. They called it the safest, quickest and least expensive way to address overcrowding and safety concerns inside prisons while reducing recidivism.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“We can address long-term staffing challenges, expand treatment and workforce training, implement evidence-based practices that reduce recidivism and save taxpayer dollars, all while, most importantly, improving public safety,” Evers told reporters during a briefing at the state Capitol.

The expansive plan, estimated to cost just under a half-billion dollars, likely faces an uphill battle with Republican lawmakers, many of whom have argued for the construction of a new prison in Green Bay to solve problems of overcrowding.

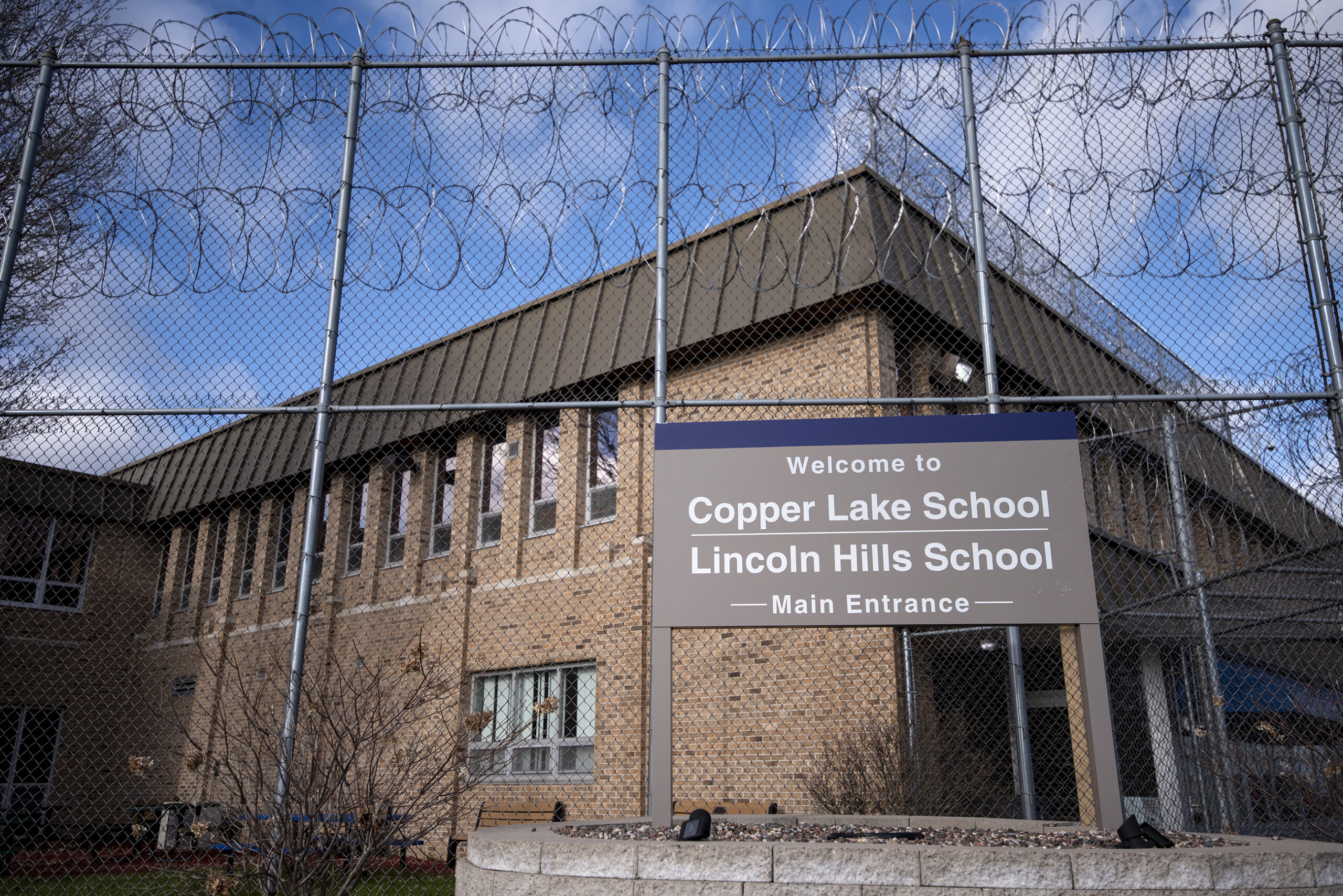

And the announcement comes after years of problems at Waupun, including a felony investigation into deaths at the maximum-security facility, and as efforts to close the notorious Lincoln Hills juvenile complex have stalled seven years after the state Legislature voted to close it down.

Hoy described Evers’ proposal as supportive of both corrections staff and taxpayer dollars.

“Essentially, this effort comes down to safety,” Hoy said. “Both in our institutions and in our communities.”

The plan will require GOP approval to go anywhere, as Republicans hold majorities in both chambers of the Legislature and will write the final budget themselves in the Joint Finance Committee.

In a statement, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, called the expansion of early release a “non-starter.”

“We have been advocating to update our prisons for almost a decade, so I’m glad to hear Gov. Evers is finally open to our ideas,” he said. “We’re willing to work with anyone who wants to add capacity so we can keep Wisconsin safe but his plan to let thousands of dangerous criminals out early is a complete non-starter for Republicans.”

Sen. Van Wanggaard, R-Racine, who chairs the Senate Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety, agreed with Evers’ call to close the Green Bay facility, but said the “devil is in the details.”

“I’m not sure his numbers add up, both in terms of costs and numbers of inmates,” Wanggaard said in a statement. “If he thinks the Legislature will rubber stamp his ideas and let a bunch of felons out of prison, he hasn’t learned anything. He cannot continue his ‘my way or the highway’ approach to governing, but if he’s willing to have an honest dialogue, I’m willing to work with him.”

A ‘domino series’ of facility changes

The complex and interwoven proposal would see most construction proposals launch around 2027, beginning a years-long process of moving incarcerated people between facilities.

It’s contingent on moving juvenile offenders out of Lincoln Hills, a troubled facility that has been slated for closure for years, and it would end with the closure of Green Bay Correctional Institution, with a rejiggering of other prisons that would reduce the overall capacity of the system by about 700.

“In order for my plan to work, several crucial steps must happen, and they must happen together,” Evers said. “All these steps are interconnected, so this plan is contingent upon each of these steps happening in concert. They must happen in tandem.”

The Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake juvenile facilities would be converted into a 500-bed, medium security men’s facility at a cost of about $9 million. The state would also construct a new juvenile facility in Dane County for $130.7 million to absorb the rest of that population, “and get our kids closer to home as soon as we safely and responsibly can,” Evers said.

The next dominoes include converting the Stanley Correctional Institution in Chippewa County into a maximum-security prison for about $8.8 million, and building out the juvenile Grow Academy, in Oregon, Wis., for $31.1 million.

The most expensive part of Evers’ plan calls for putting $245.3 million toward transforming the Waupun facility — which has become synonymous with the state’s corrections troubles, including severe staff shortages and recent inmate deaths — into a medium-security “vocational village,” which would offer workforce training.

That’s “one of the most exciting pieces of the plan, and it makes me smile,” said Hoy.

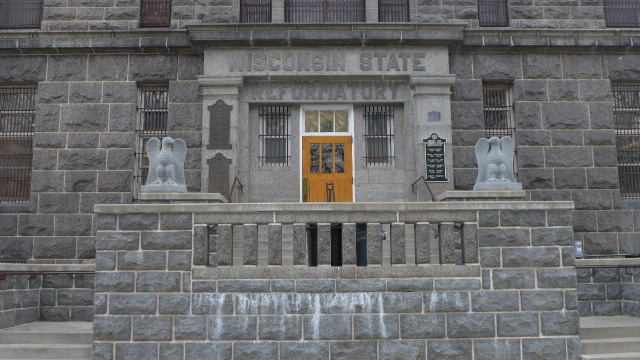

He said the plan would involve demolishing the housing unit at the 174-year-old building and replacing it with new housing and job training facilities. Hoy said incarcerated people would learn trades or receive technical training, earn certificates and partner with outside employers.

“While the vocational village concept is new to Wisconsin … it is not new in corrections,” Hoy said. “This concept has been successful in other states.”

Hoy argued that programs like these reduce recidivism and could transition people into Wisconsin’s skilled labor workforce, which faces its own shortages.

Each of those dominoes would eventually lead to the closure of Green Bay Correctional Institution by 2029, Evers said, at a decommissioning cost of $6.3 million.

Staff at GBCI would be guaranteed work at “different correctional facilities or other appropriate positions in their field without having to be rehired,” Hoy said.

The plan also includes expanding the Sanger B. Powers Correctional Center in Hobart for $56.3 million, which would increase minimum security capacity by about 200 beds, and the transformation of John Burke Correctional Center in Waupun from a male facility to one housing about 300 women.

“These are not an either/or situation,” Evers said. “These steps are each a … crucial part of this comprehensive plan, and they have to happen together. And we need Republican lawmakers to get on board with the plan.”

Evers is also requesting about $9.6 million for pay increases for corrections workers, $3.7 million for social workers and treatment specialists and $28.1 million for related programming, including staff for the newly proposed job training, recovery coaches and community-based reentry programs.

That puts the total price tag of the ask, including costs for adult and juvenile facilities, at just over $535 million.

Evers argues earned release, substance treatment will prevent recidivism

The plan would also allow people incarcerated on nonviolent charges with less than four years left in their sentence to earn earlier release through job training or substance use treatment.

Currently, people incarcerated in Wisconsin can earn early release if they are serving for a nonviolent crime and have completed substance use treatment and similar programs. This proposal would expand eligibility for completing job training, as well.

Evers’ staff estimates that would move about 2,500 people out of the system over two years, “ultimately saving taxpayers about $40,000 per person every year,” Evers said.

Wisconsin has a higher-than-average incarceration rate, and one of the largest corrections budgets in the nation, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

One reason for that high incarceration rate is because of people who violate their probation and are sent back to prison, according to the policy forum. Many of those violations are tied to substance abuse, according to a 2019 study from the Badger Institute.

Evers and Hoy argued that addressing those issues while a person is incarcerated is one way of preventing them from returning to prison.

“Our work to prevent people from reoffending must start long before they ever leave our correctional institutions,” Evers said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.