University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers recently made what they call surprising discoveries about how childhood trauma affects mental health in adolescence, thanks to a national trove of childhood health data.

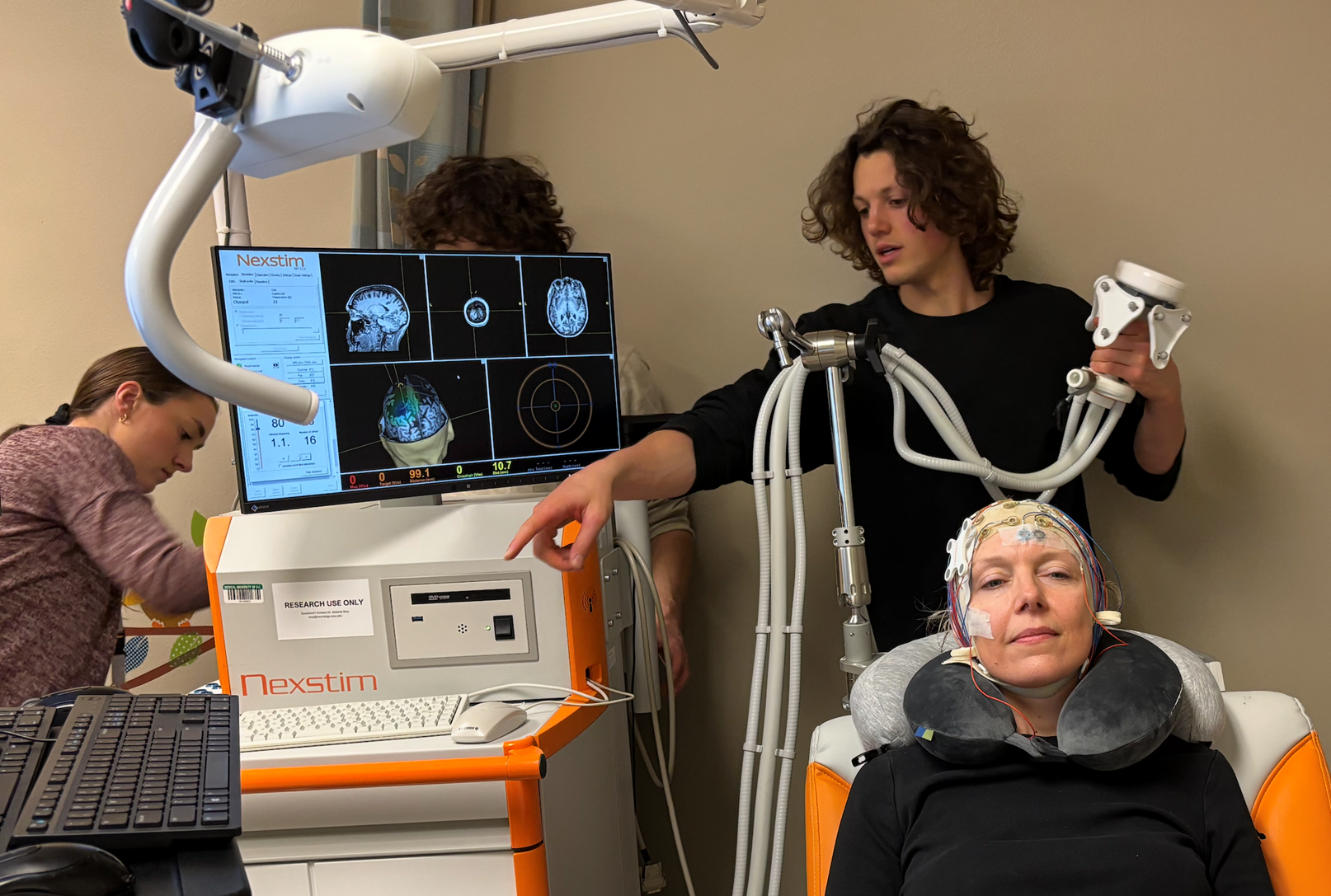

Researchers with the National Institutes of Health are in the middle of conducting the largest long-term study of childhood health in the U.S. The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study follows more than 11,000 children across the U.S. over 10 years of their life, starting at ages 9 to 10.

Using data from the first four years of that study, psychiatric researchers at UW-Madison recently found evidence to suggest that the type of trauma a child experiences could be more impactful than the sheer amount of trauma they encounter.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Since at least the 1990s, mental health researchers have known that having traumatic experiences during childhood can affect a person’s mental and physical health as they grow up. Many pediatricians use questionnaires on adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, in order to identify patients that might be at greater risk of future health problems.

However, the ACEs questionnaire has limits. By simply tallying up the number of adverse experiences a child has had, it treats all experiences as equally influential. And it can only tell physicians about a child’s general health risk — it cannot predict specific health problems.

Justin Russell, research assistant professor of psychiatry, and his colleagues at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health wanted to see if they could push past those limits.

“We wanted to build off of what we understand from the ACEs work and see: Are different forms of trauma going to be predictive of different outcomes?” Russell told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

From the data collected by the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, Russell’s team created eight themes to categorize the traumatic and adverse situations that study participants had experienced: community threat, peer aggression, caregiver maladjustment, chronic pain and medical issues, discrimination, family conflict, poverty, and interpersonal violence.

That’s where researchers discovered that the type of trauma could have more of an impact on mental health than the number of traumatic events a child experiences.

More surprising was learning that some types of traumatic experiences were actually associated with a decrease in certain mental health problems later on.

Experiences falling into the categories of caregiver maladjustment and interpersonal violence were associated with fewer outward behavioral problems like aggression, hyperactivity and impulsivity, the new research shows. Experiences falling into the categories of community threat and poverty were linked with a decline in both outward behavioral problems and inward problems like depression and anxiety.

“That didn’t make any sense to us when we first saw it,” Russell said. “The idea that kids who live in a really threatening environment would experience any reduction in mental health problems was really stunning.”

But Russell cautioned against interpreting these results as a sign of resilience and recovery. His team thinks it might have something to do with how kids express symptoms of mental distress or illness.

“What they’re actually doing is adapting to their environment in ways where they still carry the burden of mental illness,” Russell said. “But because of the context that they’re living in … they have to change the way they show it.”

Another possible explanation, Russell said, is the relatively short time scale the national study looked at. His team only studied data from when participants were 9 or 10 years old compared to when they were 13 or 14.

“It might also be that exposure to different types of trauma and adverse childhood experiences shifts the timeline for when you’re most at risk of different types of mental health problems,” Russell said. “Is this finding just a result of when we looked at these kids, or is it going to extend as they get older?”

National study participants will continue to be monitored until they’re at least 19 or 20 years old. In the meantime, Russell’s team is hoping to integrate their findings into mental health intervention efforts for youth, especially those who lack access to resources like therapy.

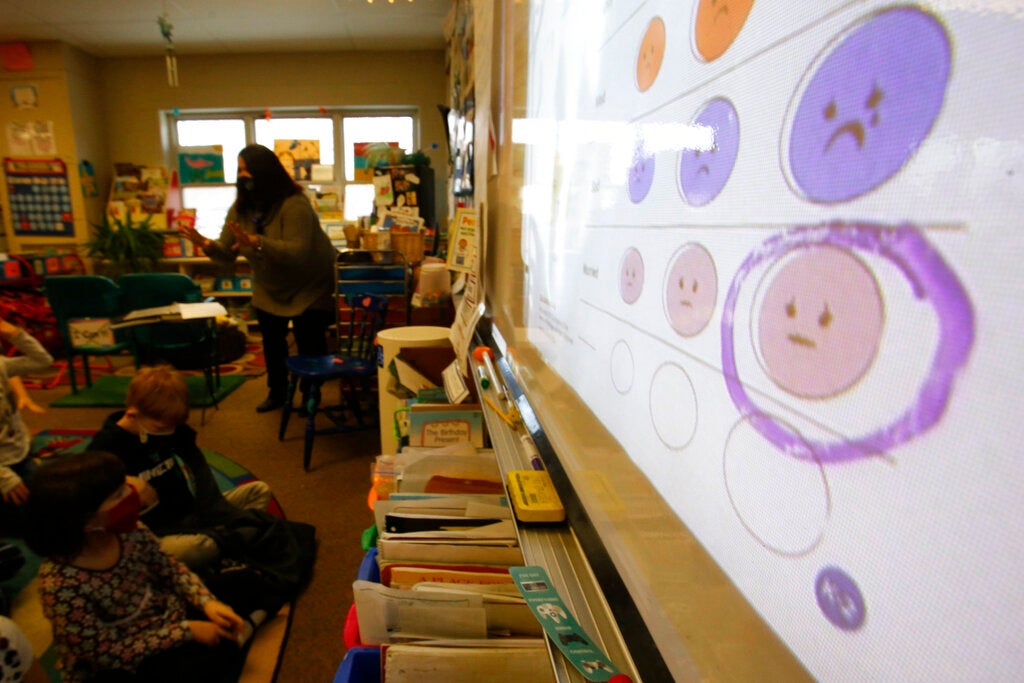

“We’re trying to find new ways of intervening that use things that kids are already doing, like video games and virtual reality,” Russell said. “We can use the knowledge that we’ve gained here in work that we do closer to home — in the community around us — to try to find what’s going to work best.”