With the start of the football season in Wisconsin comes the return of tailgates, Cheeseheads and “Jump Around.”

But in recent years, it has also brought conversations around the risks of repeat concussions and traumatic brain injuries in the sport. Among those risks is the possibility of developing Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE, which is a neurodegenerative brain disease thought to be caused by repeated head injuries.

2024 is the first year that NFL players are allowed to take extra precautions against concussions during games in the form of Guardian Caps: soft-shell covers that are worn over helmets to reduce the force of impact during collisions.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Starting in 2022, the league mandated caps for players in certain positions during pre-season practices. So far, no players on the Green Bay Packers have opted to wear the helmets in regular season games.

And while the NFL claims their research indicates that the Guardian Caps have resulted in a 52 percent reduction in concussions, there’s not much independent research that indicates they’re actually effective at protecting players.

New foam could revolutionize helmet technology

One promising development in helmet technology is being pioneered in Wisconsin, at the Thevamaran Lab in the University of Wisconsin-Madison mechanical engineering department.

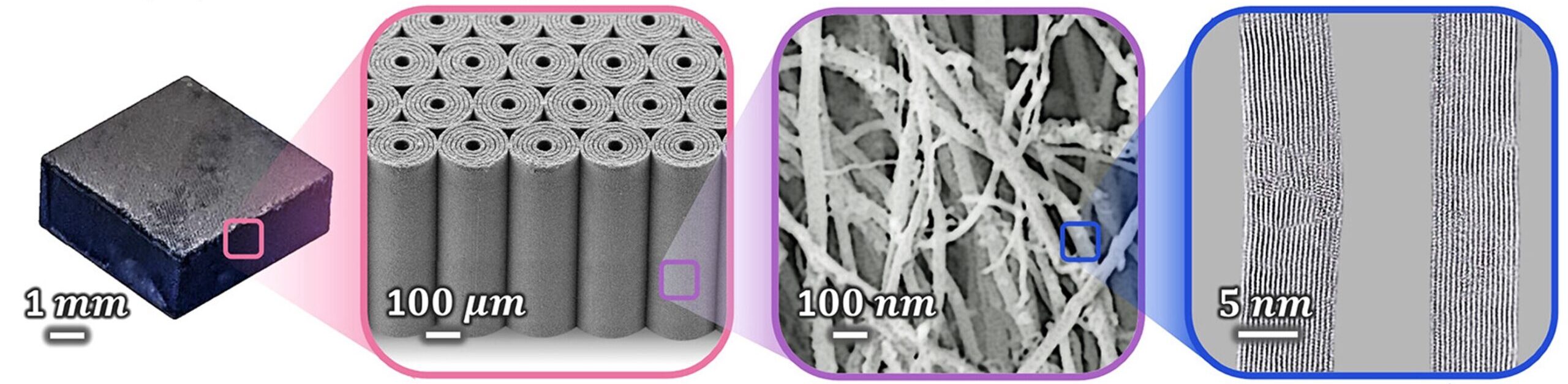

Associate professor Ramathasan Thevamaran and his colleagues developed a vertically-aligned carbon nanotube foam made up of carbon nanotubes, which has a specific energy absorption 18 times higher than the foam currently used in combat helmets.

The material also has advantages over the current material used in Guardian Caps.

“Compared to polymeric foams like what is used in Guardian Caps, this material behaves in a rate independent fashion,” Thevamaran told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “Whether you impact at low velocities or high velocities, it behaves exactly the same way.”

That means the foam is equally protective against collisions at all speeds, whether it’s many slower collisions over the course of the season or the occasional high-speed hit.

The material is also lightweight, has cooling properties and remains functional even in extreme temperature environments, so it can be used both in desert combat environments or on the ski slopes.

Thevamaran said he’s working with the cycling and military industries and hopes to eventually get the technology on the market.

Concussion treatment has come a long way

Advancements in protective equipment is just one of the ways to mitigate the risks of head injuries in contact sports.

Mike McCrea is a neurosurgery and neurology professor at Medical College of Wisconsin and director of its Brain Injury Research Program. He has also served on the NFL’s Head, Neck, and Spine Committee.

He told “Wisconsin Today” that our understanding of how to treat concussions has come a long way in recent decades, especially with regards to how long to keep concussed athletes out of play.

“Return to play after concussion has gone from 15 minutes to 15 days, in about 15 years,” McCrea said. “(It) allows adequate brain recovery and significantly reduces the risk of repeat concussion, which is where athletes get in the most trouble.”

Traumatic brain injuries remain a major concern for current and former football players — especially the possibility of developing CTE, a disease that is progressive and can be fatal. According to new research published in the medical journal JAMA Neurology, one-third of former professional football players surveyed said they think they have CTE.

McCrea said he thinks the number of players who actually have CTE is likely lower than the number of players who think they have it, and that their symptoms may have other causes.

“It’s really a tragedy when an individual believes that they may have a chronic neurodegenerative disease that has only a downward decline, when in fact their issues may be due to reversible, modifiable risk factors that could restore them to a fully functioning lifestyle,” McCrea said.

But even if not every football player will develop CTE, the consequences of repeated concussions and traumatic brain injuries is an issue that persists within the sport — and one that researchers continue to wrestle with.