Tasslyn Magnusson is a lifelong reader and booklover. She is an especially big fan of children’s literature, or what she affectionately calls “kid lit.”

“Children’s literature is so special and important,” she said. “It plays such an integral role in helping kids become whole human beings.”

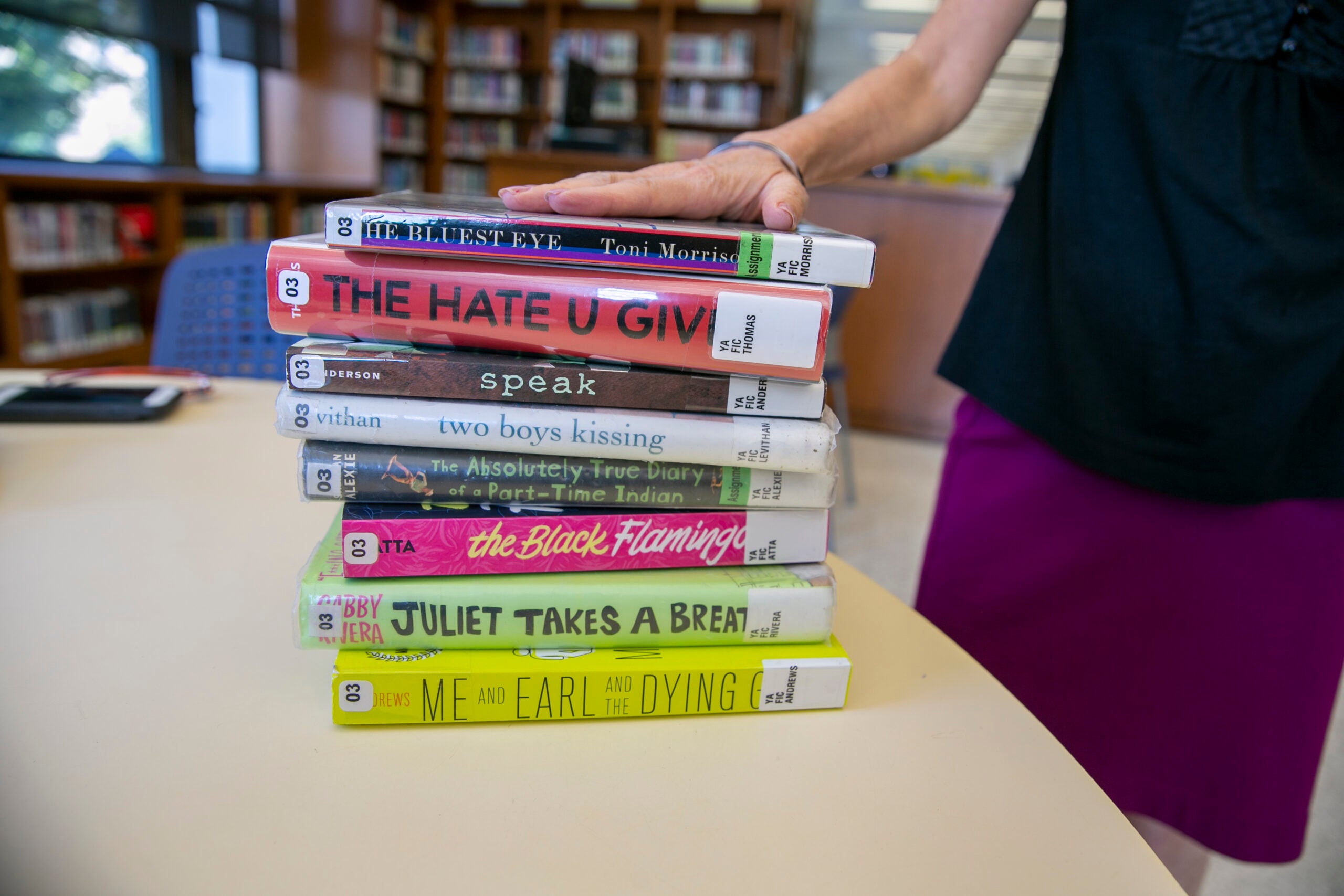

Magnusson worries about increased efforts to ban books from school libraries. Last year, Wisconsin was the second-leading state nationally in the number of school library book removals, according to a new report she and others wrote for PEN America. A big reason for that was one parent in the Elkhorn Area School District who requested a review of 444 books.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Other districts around the state are dealing with debates around book bans, too. Magnusson lives with her family in Prescott, a small town in western Wisconsin where the St. Croix River and the Mississippi River meet. She said local school districts have been feeling the strain of increased book challenges, which often lead to heated discussions at school board meetings.

An aspiring children’s author herself, Magnusson started participating in the “kid lit” community on social media after getting a master’s degree in writing for children and young adults. That’s when she first noticed that some of her own favorite authors, including young-adult fiction writer Laurie Halse Anderson, were having their books taken off shelves.

In 2021, Anderson posted on X that her 1999 novel “Speak” seemed to be getting banned more often. She suggested that someone should start tracking book bans around the country.

Magnusson took note.

“I was like, ‘Wow, Laurie Halse Anderson asked. I can do that. I know how to use a Google spreadsheet,’” Magnusson recalled on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “So, I took it upon myself to make a spreadsheet. And here we are three years later.”

Magnusson started pulling book ban data from local news sources around the country. Her spreadsheet circulated online and quickly became a popular resource among authors and librarians. The nonprofit organization EveryLibrary picked up the spreadsheet and partnered with Magnusson in hosting her “Book Censorship Database.” This is around when she became a program consultant for the Freedom to Read program at PEN America.

For Magnusson, creating the spreadsheet put her in the spotlight and set her on a path to advocating for children’s literature with a new intensity.

“Now I am a banned book queen,” she said with a laugh.

Librarians are feeling the strain of increased book bans

There’s an emotional toll for school staff during these book ban debates, Magnusson said. After releasing her spreadsheet, she started fielding calls and messages from librarians.

“They would call me and they would cry … because they had no place to turn. They felt overwhelmed. They felt demonized,” Magnusson said. “I’ve talked to so many librarians who have been doxed, who have been attacked by community members.

“They’re called groomers or sexual predators,” she continued. “It’s utterly devastating for them.”

Last year, Republicans in the state Legislature proposed a new bill that would allow school and library staff to be prosecuted for providing “obscene” materials to minors. But the bill ultimately failed to pass.

Some parents are pushing for book bans, and others support diverse library collections

While research from Wisconsin Watch shows that political groups and “super requesters” are driving a lot of the school book bans, it’s easy for things to get heated even when an individual parent raises a concern about books their children could read.

“A lot of these complaints and concerns come from a place of real fear and worry for one’s kids,” Magnusson said.

Her advice to parents who have a concern about a specific book is to first go to the teacher who assigned the book or the school librarian.

“What I hear from so many librarians is that nobody is talking to them. (Parents are) going right to these public comment periods at school board meetings,” Magnusson said. “Librarians would love to talk to you about their processes for collecting material for schools.”

When it comes to librarians and school staff, Magnusson’s biggest advice is to stay calm and be transparent about the review process. This can “lower the temperature” of the debate.

Magnusson hopes that parents who are against banning books from school libraries will make their opinions known by thanking their librarians directly and voicing support in public meetings.

“Just talk about why a public education and your school library matters,” she said. “Remind everyone that there are parents who are across the spectrum politically (and) culturally, and that you’re there standing in support of your public schools.”

Magnusson: When books are taken off shelves, students are most affected

When Magnusson started her spreadsheet three years ago, she was initially inspired to support authors from the “kid lit” community. But all along the way, the young readers have been at the forefront of her mind.

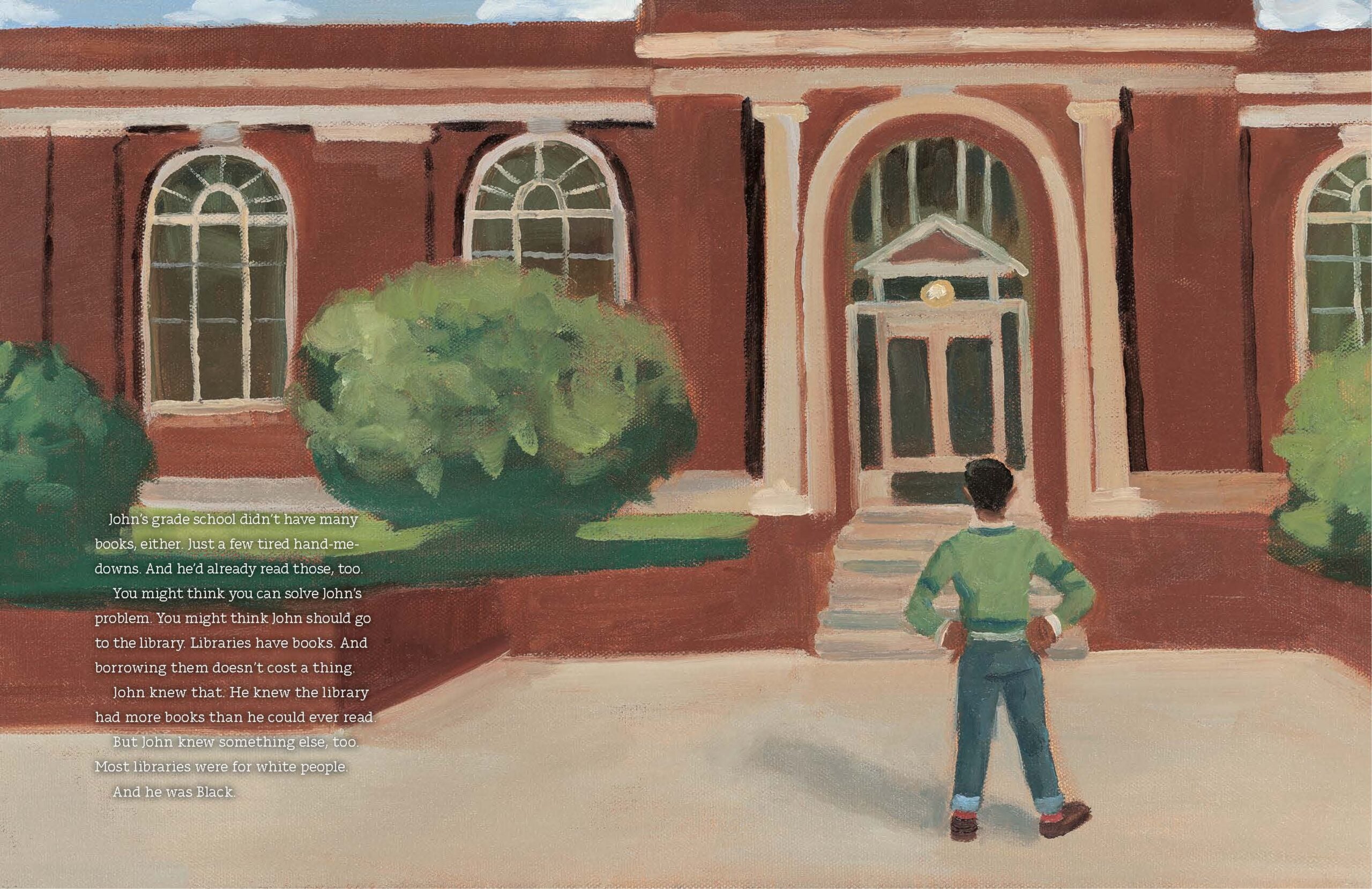

Having a book temporarily pulled from the shelves might not seem like a big deal to adults, she said. For kids and teens, on the other hand, waiting a month could make a big difference.

“When we pull tons of books off shelves to review them, we’re keeping them out of the hands of kids who really need them at that moment in time,” Magnusson said. “For a kid, the need for that book at that time is brief.”

And for many students, Magnusson said reading is more than just educational — it’s a way to navigate their own identities and emotions at a pivotal time of their lives. This is especially important for teens. More than half of high school students in Wisconsin are struggling with their mental health, according to the latest report from the Department of Public Instruction.

“For a young person … sometimes the school library is the only safe place for them,” Magnusson said. “That’s the only place they can get (a book) and be safe and learn about their world. It’s awful when that is closed to them.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.