University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers are receiving a $150 million grant to study how Alzheimer’s and other dementias affect the human brain.

The grant, provided by the National Institutes of Health, provides an “extraordinary opportunity” to better understand Alzheimer’s and how it interacts with other neurological diseases, according to the study’s lead researcher.

“We now know that Alzheimer’s disease usually does not occur by itself. It usually occurs with at least one other brain condition,” said Sterling Johnson, a professor of medicine at the university, during a recent interview on WPR’s “The Morning Show.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The NIH grant is the largest of its kind for UW-Madison. Researchers anticipate receiving the funding over the next five years. Johnson and other scientists will work alongside the nation’s 37 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers, which study a group of over 17,000 individuals.

On “The Morning Show,” Johnson discussed study expectations, methodology and health advice.

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: One aim of the study is to develop a standardized test for analyzing hallmark biomarkers of Alzheimer’s. What do you mean by hallmark biomarkers?

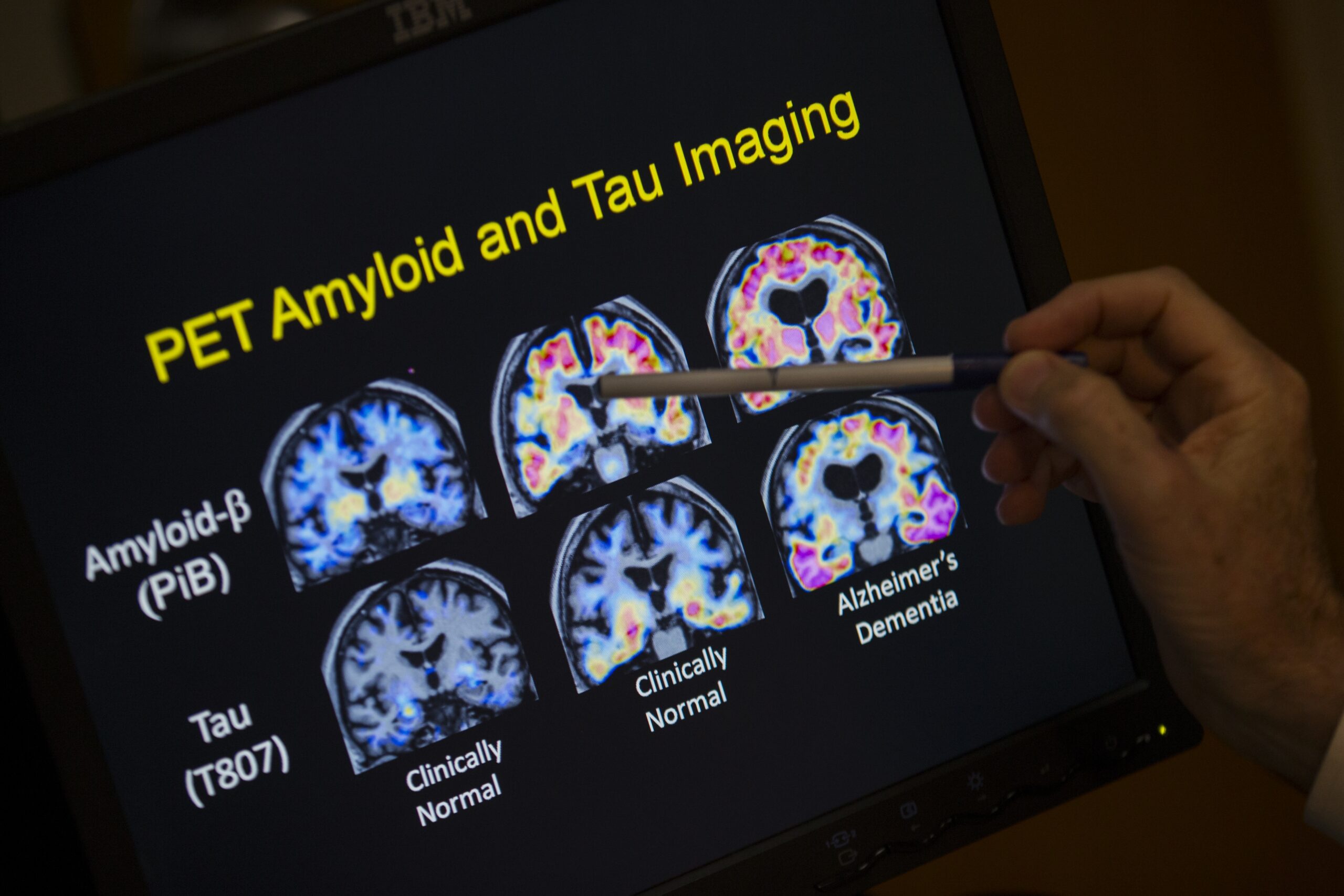

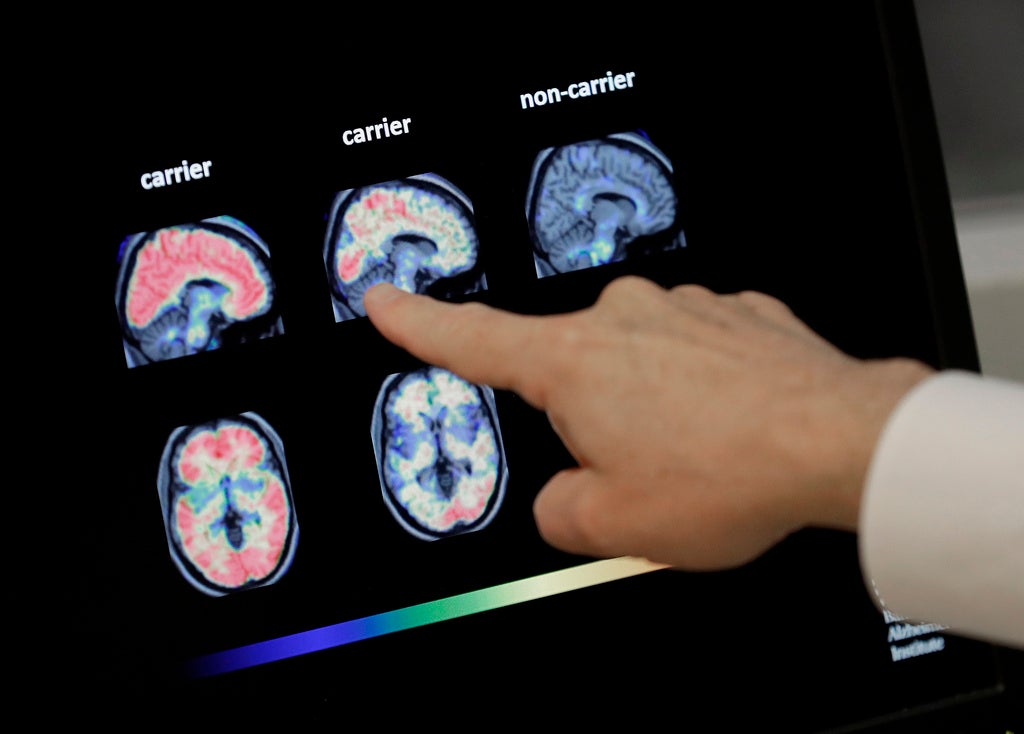

Sterling Johnson: Biomarkers are the way we look at the brain. They are a tool to understand what’s going on. In this case, we’re looking at the hallmark signs of Alzheimer’s disease. … And we can actually see those with some advanced brain imaging techniques that all of these Alzheimer’s centers have the capability of using.

KAK: These participants in the study, what might they encounter along the way as you follow them?

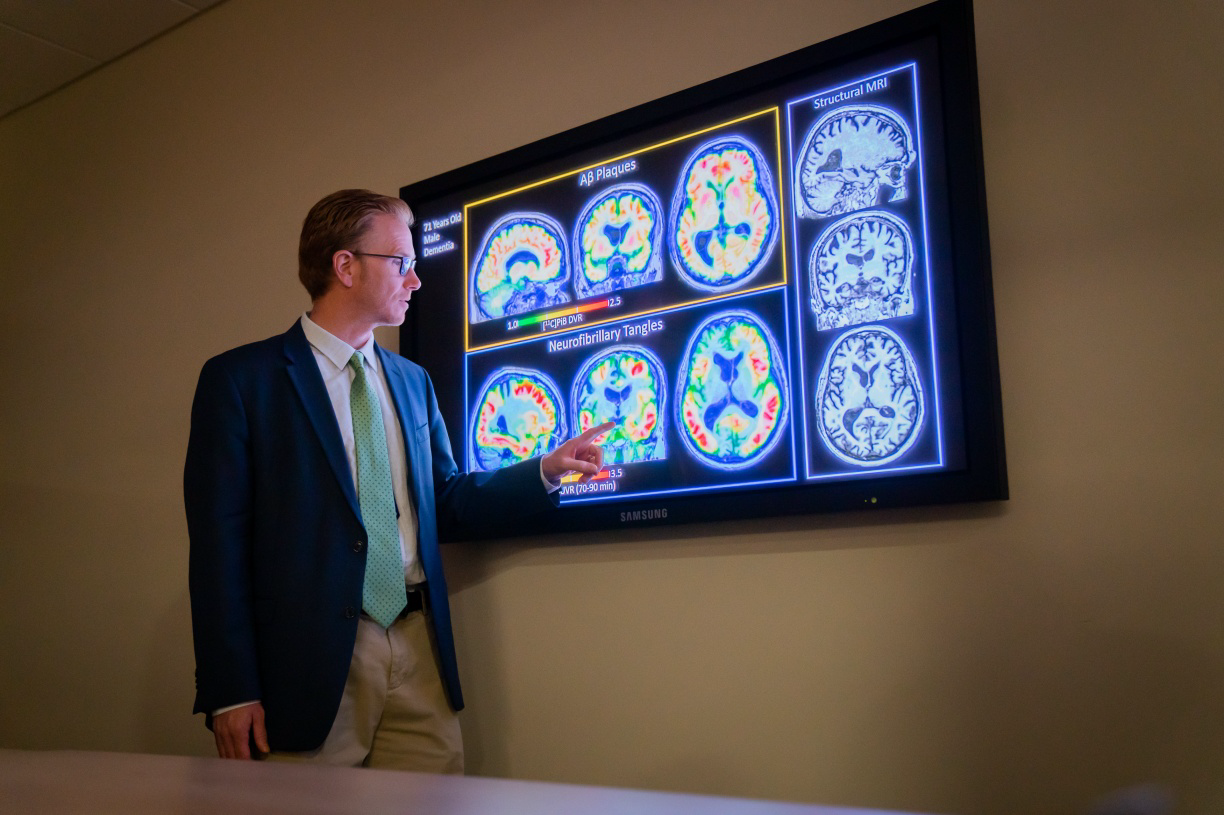

SJ: They will come in and go through several different types of imaging. One will be this scan that looks for amyloid plaques. Then another imaging procedure would be a scan that looks for neurofibrillary tangles. The image helps us see where they are in the brain. We would do an MRI scan as well.

The other thing that we’ll be gathering alongside these images is blood. That’s something we can talk about, because it’s now possible to detect some of these diseases with a blood test. We’ll be evaluating new tests as we go along and using established tests as well.

KAK: There are a bunch of blood tests that doctors can order to figure out whether their patient with memory loss also has Alzheimer’s disease. What can you tell us about these blood tests?

SJ: Most of them are available for research so that we can evaluate them and know how good they’re going to be in different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re learning so far is that they’re almost as accurate as these very fancy and advanced imaging scans. That’s really exciting, because that means we’ll be able to get these diagnostic techniques out to the community in a way that improves their care. One of our major goals of this study is to bring confidence to the community about the value of the usefulness of these blood markers.

READ MORE: National Alzheimer’s research led by UW-Madison boosted by $150M grant

KAK: Your study is working with 37 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers covering over 17,000 patients. How complicated is working with that many people and that many research groups?

SJ: We’re finding out that it’s quite complicated. But these centers are really the most qualified and expert research workforce in the country. They see complicated patients. They’re well-attuned to the kinds of things that we’re doing.

KAK: You are recruiting participants who are at least 55 years old and are experiencing either mild dementia or no current impairment. Why start there?

SJ: First of all, Alzheimer’s disease can start many years before its symptoms. So, we need to start with people who are not symptomatic. We want to track how this disease unfolds and develops over the course of a person’s older adult lifespan.

We’re also very interested in the people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia, because that’s where mixed dementia really comes into play. By the time a person has cognitive symptoms, they may be experiencing not just Alzheimer’s but some additional co-pathology.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.