Wisconsin Supreme Court justices questioned Tuesday whether the state Department of Natural Resources should be forced to designate emerging contaminants like PFAS as hazardous substances before the agency is allowed to regulate them.

The court heard oral arguments in a case brought by Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, which sued the DNR on behalf of Oconomowoc-based dry cleaner Leather Rich in 2021.

Wisconsin’s powerful business lobbying group is arguing the agency can’t force businesses to test and clean up PFAS without first designating the chemicals as hazardous substances. A Waukesha County judge and state appeals court sided with WMC.

Enacted around 50 years ago, Wisconsin’s spills law requires anyone who causes, possesses or controls a hazardous substance that’s been released into the environment to clean it up.

Assistant Attorney General Colin Roth, who represented the DNR, said there’s no dispute that a PFAS spill is hazardous.

“We’re dealing with environmental spills. There’s no free lunch,” Roth told justices. “Someone’s got to pay for it. It’s either the taxpayers, or it’s the people who discharge or possess the land on which the discharge occurs. That’s the choice. Someone’s got to do it.”

Justices asked lawyers for Leather Rich and WMC whether they believe PFAS meets the definition of a hazardous substance.

“No, I don’t agree with that,” said Lucas Vebber, an attorney for WMC. “But I think the appropriate way for the agency to make that determination is to promulgate it as a rule.”

Promulgating a rule, which carries the force of law, can take years, and gives the Legislature the power to shape or block a proposal in the process.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In its lawsuit, WMC argued on behalf of Leather Rich that the DNR instead issued an interim policy under a voluntary cleanup program that required participants to test for PFAS and address contamination. They claim that the interim decision is an unlawfully adopted rule that can’t be enforced.

Vebber said the DNR should provide a list of substances and criteria so the public knows when they’re violating the spills law.

Liberal Justice Rebecca Dallet said requiring the agency to do that for all hazardous substances before they can take action to address them “is insane.”

Conservative Justice Brian Hagedorn asked an attorney for Leather Rich whether she believed the DNR could not take action to address a substance that everyone agrees is hazardous until rulemaking is done.

“Yes, but I think rulemaking would be a very easy endeavor in that case,” company attorney Delanie Breuer replied.

Liberal Justice Jill Karofsky interjected: “I don’t think rulemaking is an easy endeavor in any case.”

Karofsky asked whether those responsible for PFAS contamination would have to report a spill if the court sided with WMC and Leather Rich. Breuer said that wouldn’t be required until rules are put in place.

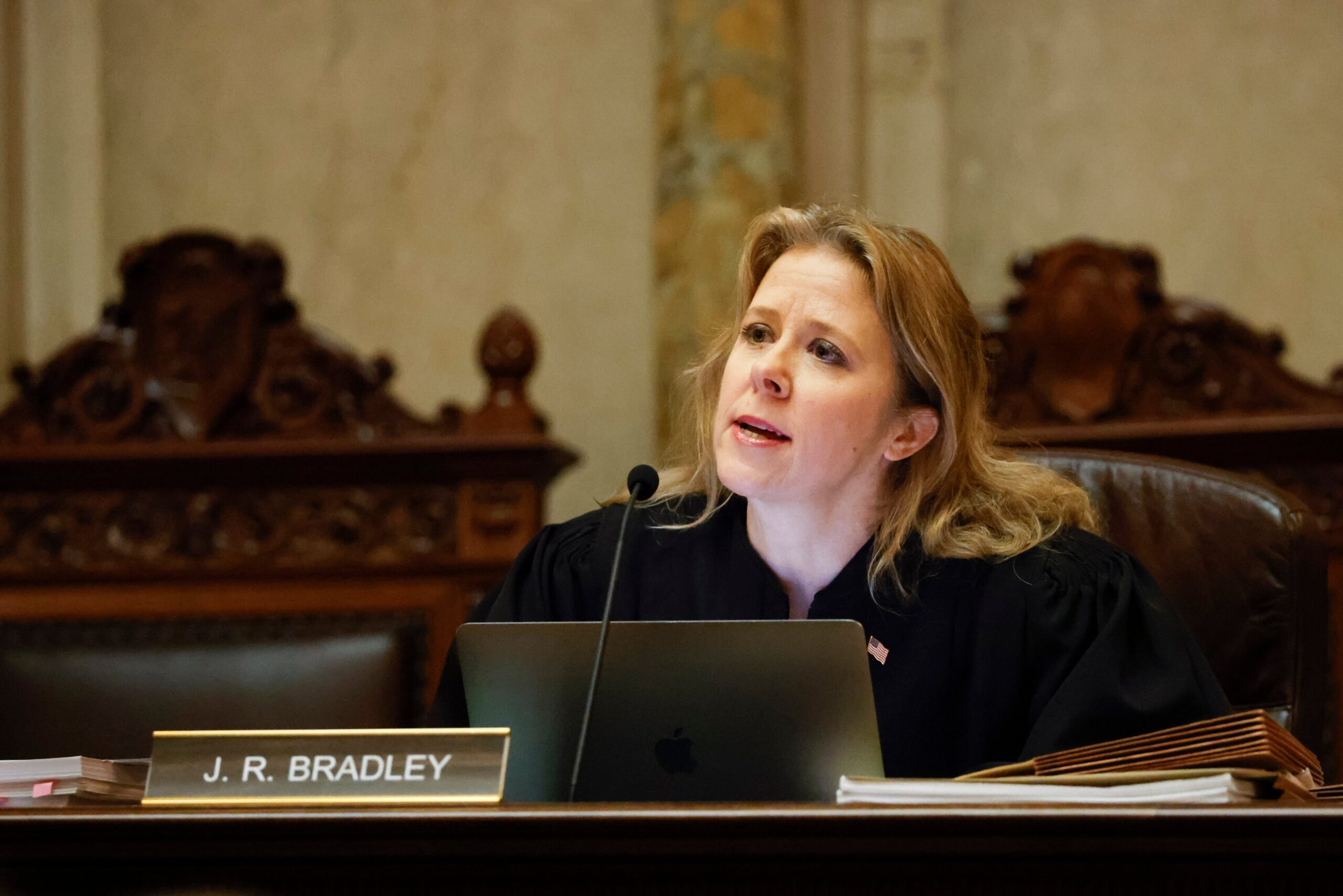

Conservative Justice Rebecca Bradley argued that Leather Rich is not a business that’s trying to avoid the law.

“Their principal complaint, as I understand it, is they don’t know what it is,” Bradley said. “And the government’s counter is, ‘Well, you have to figure it out for yourself.’”

However, Hagedorn said there’s nothing in the law that states agencies can’t act until a rule is in place if the Legislature has already passed broad, or even somewhat vague laws.

“I’m unaware of any principle of law that makes that a general rule that always applies,” Hagedorn said.

A lengthy dispute over PFAS

Since the lawsuit was first filed, federal regulators have placed limits on PFAS in drinking water and designated two of the most widely studied chemicals as hazardous substances.

The state has also set less restrictive drinking water limits on the chemicals. Even so, PFAS standards are lacking in groundwater after the DNR was forced to abandon regulations due to excessive compliance costs.

Environmental advocates say the case heard by the court Tuesday is part of a broader effort by the Republican-controlled Legislature to impose barriers to rules that set standards to protect public health and the environment under a 2017 law known as the REINS Act.

Environmental groups and residents who have intervened in the case say a ruling in favor of the business group would undermine protections for cities dealing with PFAS contamination like Marinette and Wausau, according to Rob Lee, an attorney for Midwest Environmental Advocates.

“It could upend the long-standing implementation of the spills law in Wausau and throughout the state by forcing DNR to go through a lengthy and virtually impossible rulemaking process before it could take action to address almost any toxic spill,” Lee said. “As a result, Wisconsin would be forced back into the dark ages of environmental protection, where we would likely remain for a very long time.”

Lee said the outcome of the case could also affect a lawsuit filed by Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul against Tyco and Johnson Controls for violating the state’s spills law. The DNR referred the companies to the Wisconsin Department of Justice for failure to report any release of PFAS when the chemicals were first discovered at Tyco’s fire training facility in 2013. Company officials maintain they believed contamination was confined to its site.

PFAS are a class of thousands of synthetic chemicals used in everyday products like nonstick cookware, stain-resistant clothing, food wrappers and firefighting foam. The chemicals don’t break down easily in the environment. Research shows high exposure to PFAS has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, fertility issues, thyroid disease and reduced response to vaccines over time.

Both Republicans and Democrats in the Legislature have put forth bills to address PFAS contamination and allow groundwater standards to move forward, but those proposals failed in the last legislative session. Lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle say they plan to introduce bills to address PFAS.

Wisconsin communities large and small are struggling with PFAS contamination. They include the cities of Marinette, Eau Claire and Wausau in addition to towns like Peshtigo, Campbell and Stella.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.