The Wisconsin Supreme Court is weighing whether an inmate’s conviction for stabbing a prison guard should be dismissed because it took 46 months for the trial to conclude.

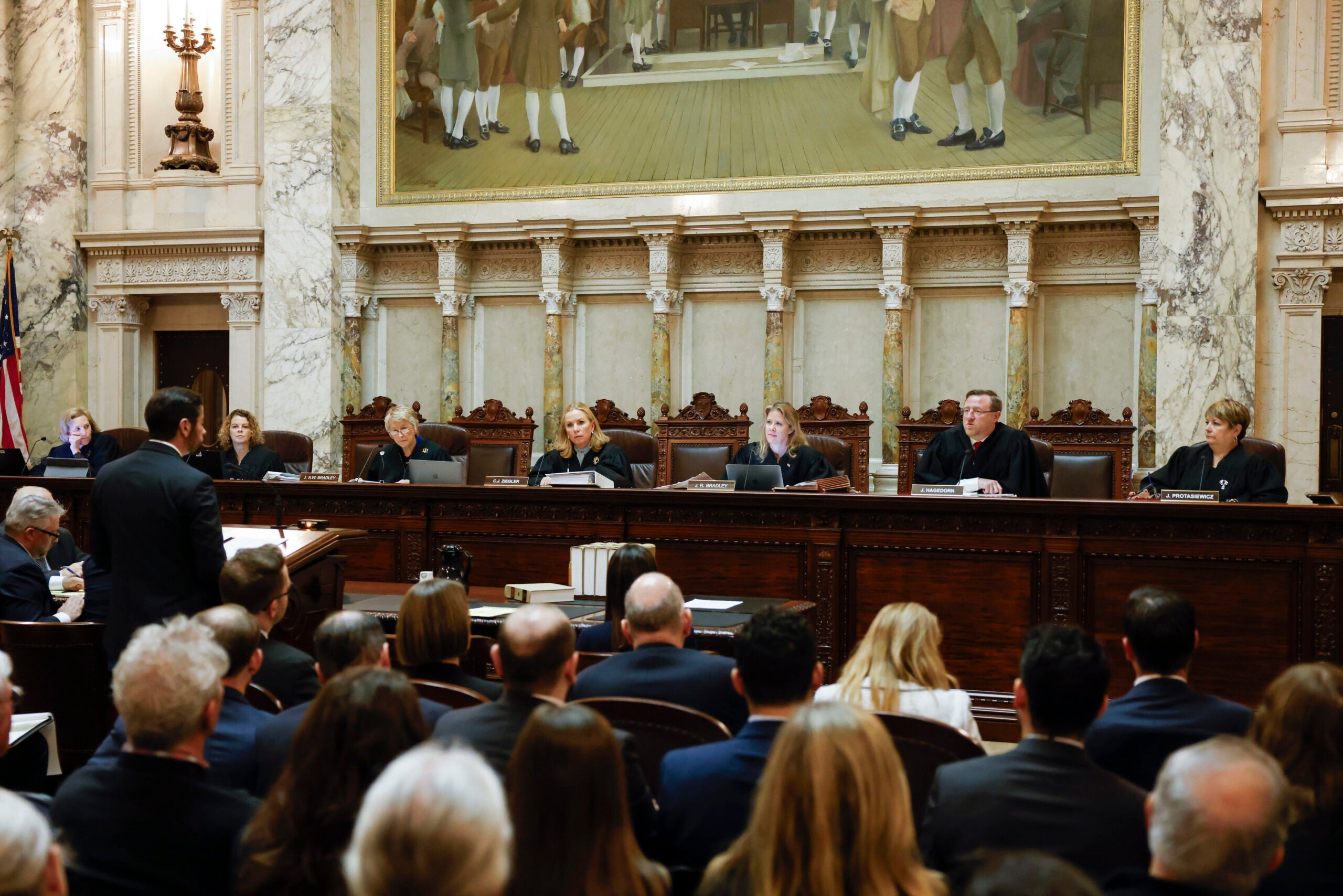

During oral arguments Tuesday, justices appeared skeptical, with some suggesting a state appeals court was wrong when it ordered the conviction to be dropped.

The case before justices involves Luis Ramirez, who is currently serving a 40-year sentence for an armed robbery conviction in 1997. On May 5, 2015 Ramirez attacked a correctional officer at the Columbia County Correctional Institution, stabbing him in the head and neck with a sharpened pencil.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Ramirez was charged with the crime in February 2016, but the case didn’t go to trial until 46 months later. He was convicted of the assault in 2019 and later filed a motion alleging the delay violated his constitutional right to a speedy trial.

Wisconsin’s District 4 Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Ramirez in April 2024, ordering the circuit court to dismiss the charges against him. The three judge panel said it was the longest delay of any published speedy trial case in Wisconsin since 1972. The opinion blamed the “vast majority” of the delay on the state, calling it “extreme.”

The Wisconsin Department of Justice appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and on Tuesday, Assistant Attorney General John Flynn told justices that Ramirez’s constitutional rights weren’t violated because he didn’t request a speedy trial until nearly three years into the case. Flynn also argued Ramirez didn’t offer proof the delays were intended to hurt his defense.

‘How much of a delay is too much?’

Flynn said the bigger issue is what he called a confusing and “unworkable” precedent from the state appeals court that would require prosecutors to explain why a case didn’t come back to court sooner even if there are valid reasons for a delay.

“How much of a delay is too much?” Flynn said. “How much time does a valid reason get the state? That’s massively unclear after the Court of Appeals decision.”

Ramirez’s attorney, Jennifer Lohr, disagreed and told justices the appeals court was right to reverse his conviction. She pushed back when conservative Justice Rebecca Bradley asked whether Ramirez waiting nearly three years to request a speedy trial should weigh against him.

Lohr said Ramirez did wait a long time, but said it was partly due to court hearings getting rescheduled.

“When we get to that trial date five or six months after the preliminary hearing, it gets rescheduled and pushed out again,” Lohr said. “And so, he’s waiting for these trial dates to happen, and they keep not happening and keep getting pushed back.”

The Department of Justice argued part of the delay was due to a district attorney’s retirement, which left prosecutors unable to properly prepare. Liberal Justice Janet Protasiewicz, who worked in the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s office for years before becoming a judge, took issue with that claim.

“I do expect somebody can come up to speed and be able to try a case where the facts to me seem relatively simple,” Protasiewicz said.

Flynn said the court can hold that specific delay against the state if it wants, but “it shouldn’t weigh heavily against the state.”

“It is a reason that happens due to life and retirement,” Flynn said.

Appeals court ruling scrutinized

Other justices took issue with the District 4 Court of Appeals’ ruling, including its criticism of the lack of a documented court record explaining the delays.

Liberal Justice Jill Karofsky said judges don’t have time to go through their calendars and outline all of the various hearings ahead of them for the court record.

“Is that really what we want circuit courts to be doing?” Karofsky asked. “Because if we do that in every single case, it is going to be an enormous, enormous time-suck for circuit court judges.”

Lohr responded by saying judges don’t need to share their calendars, but a “simple statement” outlining what future court dates would work. Bradley interrupted and said that’s already being done.

Bradley said the state appeals court made multiple errors when interpreting a 1972 U.S. Supreme Court decision establishing tests for judges when considering whether a person’s right to a speedy trial has been violated. One of those is what degree of harm a defendant faces by court delays.

“What prejudice did your client suffer?” Bradley said. “He was going to be in prison for a very long time, so his liberty interest was not even implicated with this delay.”

Lohr said that’s true, but Ramirez testified that the pending charges against him caused added stress and anxiety rising to the level of presuming prejudice against him in the case.

“So, if there is an excessive delay, we assume that there was some prejudice,” Lohr said. “It’s prejudice that can’t always be quantified or demonstrated.”

Karofsky told Lohr that was asking the courts to balance factors that can’t be measured.

“I’m not seeing any prejudice here,” Karofsky said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.