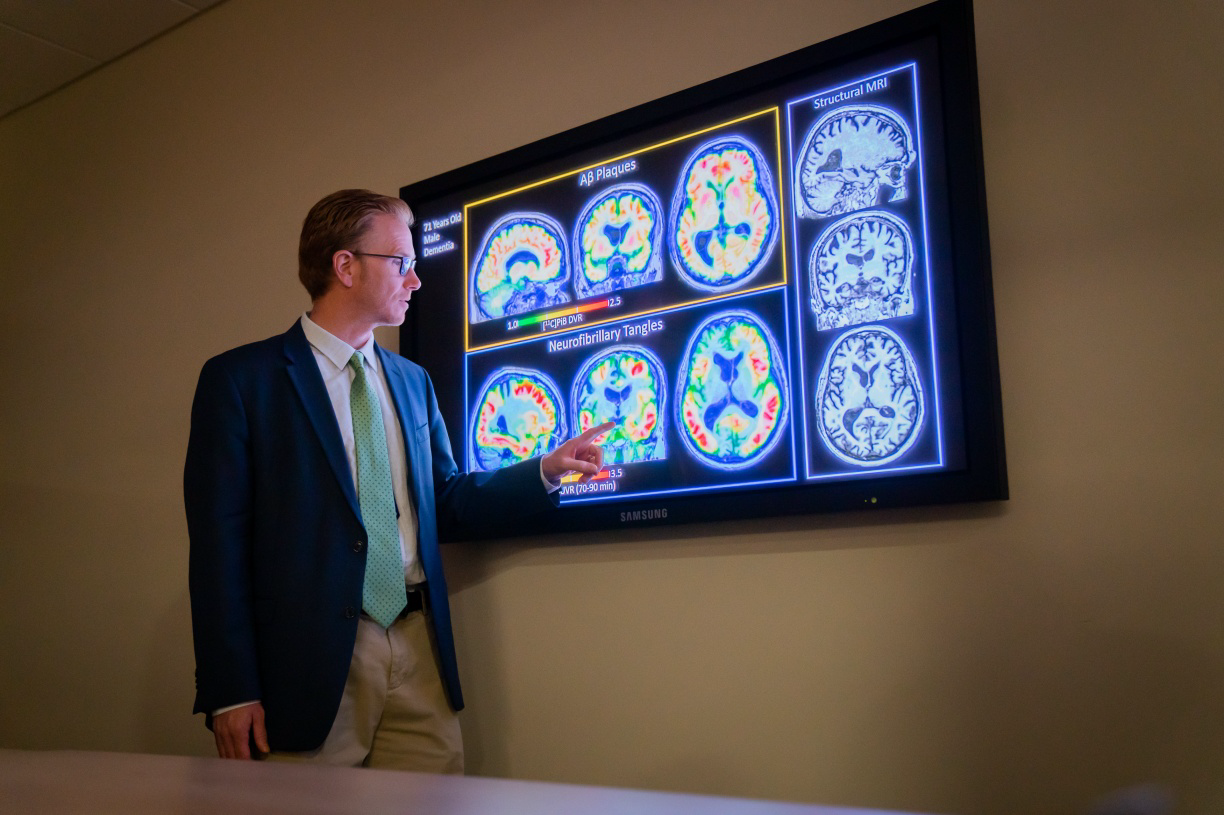

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have collected brain scans in a first-of-its kind study on Alzheimer’s disease.

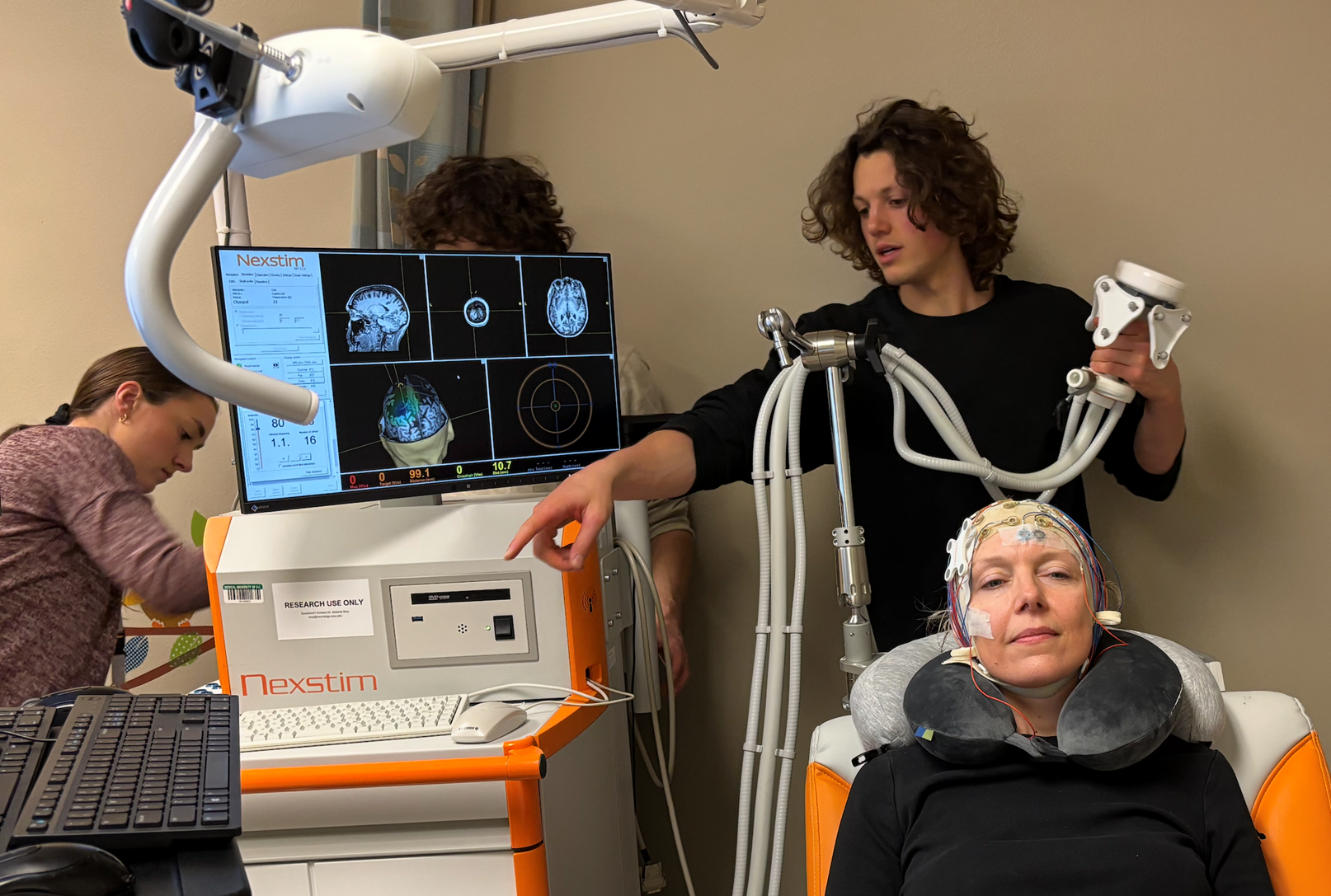

The national research project is working to gather comprehensive brain imaging and blood-based biomarkers from 2,000 participants across the country.

The data, which is collected from individuals twice over three years, will allow researchers to track biological signs of Alzheimer’s in order to better understand the disease. Scientists also hope the research will further understanding of other types of cognitive impairments or dementias in older adults.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The study is a collaboration of 37 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers across the U.S. and received a $150 million grant from the National Institutes of Health earlier this year. The research center at UW-Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health was chosen to pilot the first series of brain scans starting in August.

Barbara Smith Ballen from Madison was one of the first to participate. Her father was diagnosed with dementia in the years leading up to his death. She said a few of her close friends have gone through similar experiences after having a family member diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Smith Ballen, who admits she’s not a fan of blood draws or hospital visits, said she hopes the study will lead to improvements in diagnosis and treatment.

“I just have such motivation and compassion for this particular disease, and trying to really help the researchers that seem very dedicated to finding results,” she said.

Ozioma Okonkwo, a UW-Madison professor helping to lead the project, said they’ve continued to see strong public interest in Alzheimer’s disease research.

“Some of them may not even currently have a loved one with Alzheimer’s,” Okonkwo said. “We need both types of individuals in the study to enable us to begin to drill down and say what are some of the earliest signals that we might be able to detect in the brain or blood or spinal fluid of these two classes of individuals.”

Okonkwo’s focus within the project is to collect better data on the biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease from Black and Latino individuals, who are twice as likely to have dementia.

He said participants in past research studies have been primarily white and scientists have found the results don’t always translate to people from other races and ethnicities.

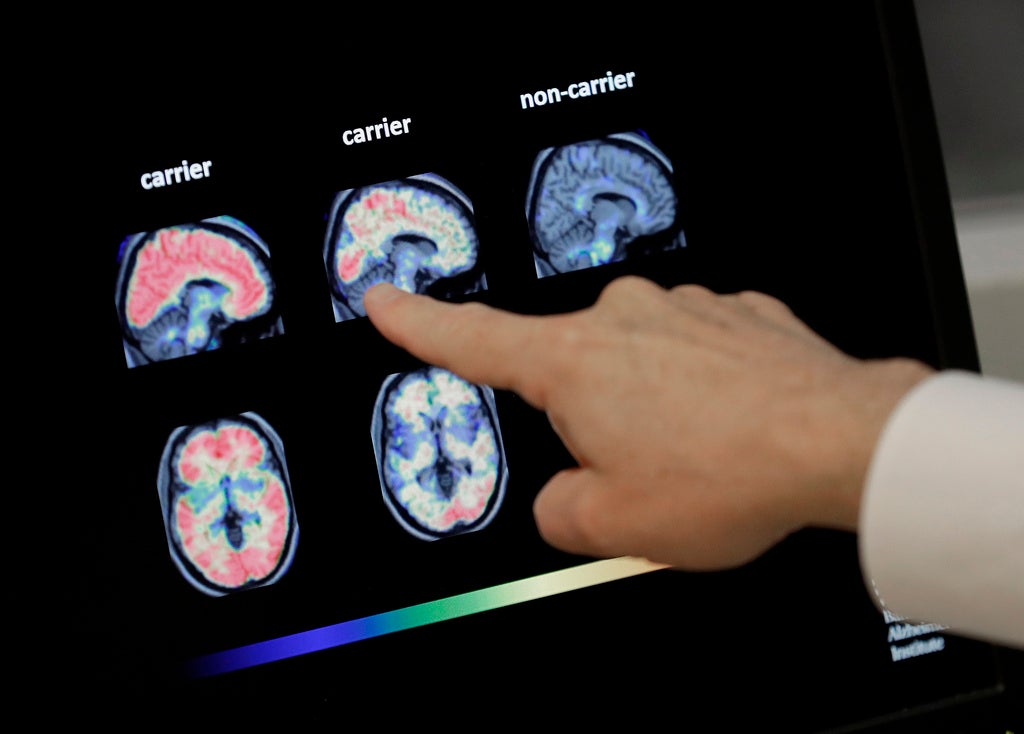

As an example, he points to the well-established finding that a build up of amyloid plaques in the brain are what cause Alzheimer’s. Okonkwo said more recent research has found that Black and Latino patients don’t always have higher amounts of amyloid plaques when they develop Alzheimer’s.

“That is why it is very critical for a study of this magnitude that we enroll a large enough subset of underrepresented folks,” he said. “Why is it that these individuals from these minority groups are more likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and other types of dementias in the clinic, but they do not necessarily have a greater burden of the disease itself in the brain?”

The project is dedicated to recruiting at least 25 percent of patients from communities historically underrepresented in research.

Smith Ballen, who is Black, said she is glad to see representation as a priority of this work. She hopes to encourage other people of color to participate in the study.

“Without them joining, there’s not a lot of input from people of color to continue to be represented in these studies, and therefore continue to help with the prevention and cures of this devastating disease,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.