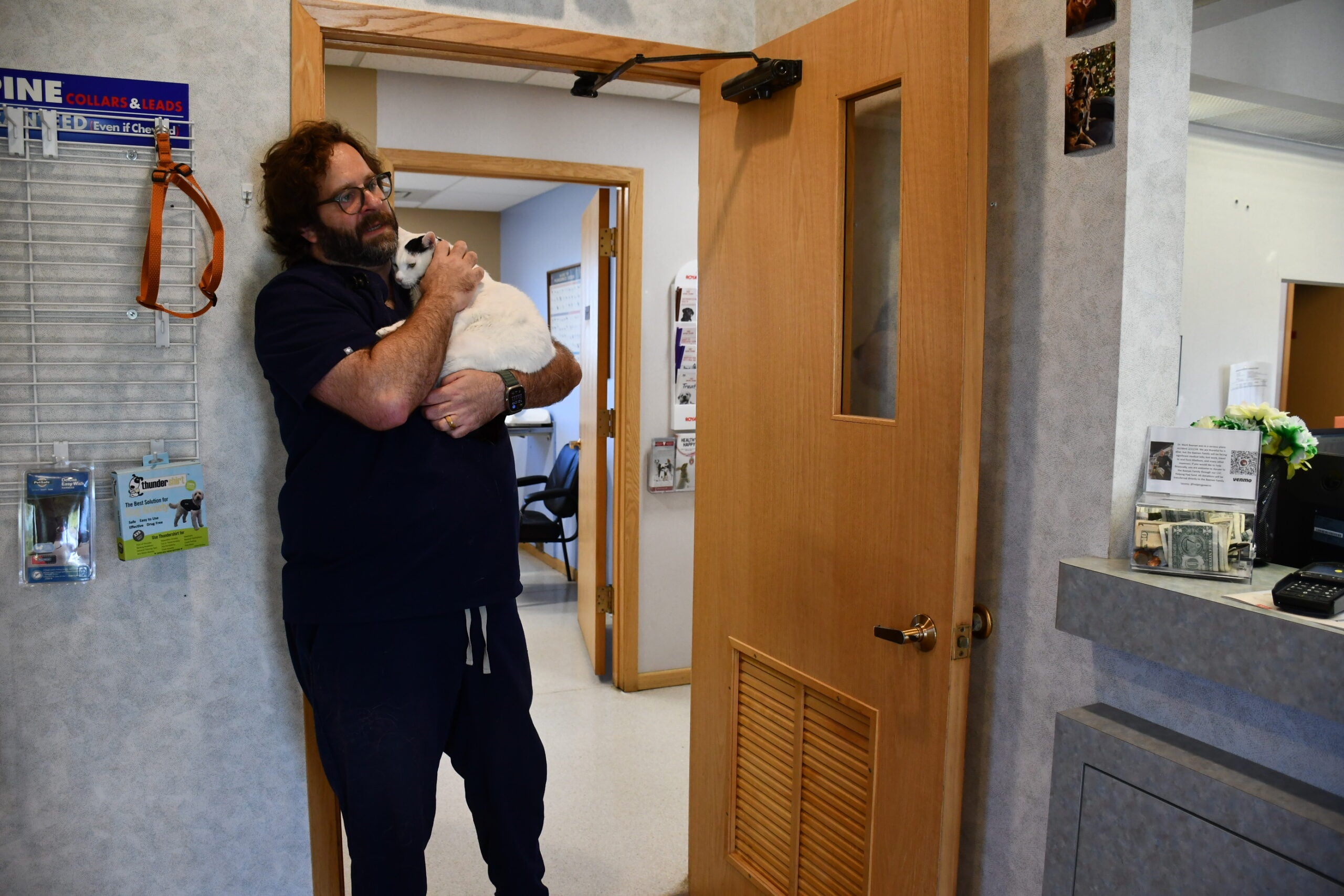

Whenever Dr. John Dally opens the email inbox of his veterinary clinic in Spring Green, he often sees a request from a corporation asking to buy his practice.

“We get solicitations constantly,” he told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” “At least a couple times a week.”

That’s because veterinary clinics are becoming big business for corporations and private equity firms around the country. Today, at least 25 percent of general practice vet clinics are owned by corporations. Some estimates show that number could increase to 60 percent over the next decade.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But Dally is uninterested in selling his 20-year-old clinic to a corporation.

Instead, Dally’s Spring Green clinic and his fellow colleagues at Mazomanie Animal Hospital last year opened Cooperative Veterinary Care, a co-op that might be the first employee-owned veterinary cooperative in the country, according to the University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives.

The 14 employee owners include veterinarians, vet technicians, vet assistants and a receptionist. Each owner is on the board of directors. They get equal voting power on decisions and a share in the end-of-year profits based on the number of hours worked.

Together, the group makes decisions on health care, pricing structure, wage tiers and employee benefits.

“I like to think of it as an analogy to the Continental Congress in the formation of this country,” said Dr. Eric Howlett, an employee owner at Cooperative Veterinary Care and former board president. “We’re coming together, forming our bylaws and asking: What are our shared values?”

And the group casts votes by animal noises instead of saying “yea” or “nay.”

“I mean, ‘yea’ and ‘nay’ are so boring,” Howlett said. “So, sometimes it’s a ‘woof’ or ‘meow.’ Sometimes, it’s a ‘moo’ or a ‘neigh.’”

The changing ownership of veterinary clinics has local effects

Dally graduated from the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine in 1992 and has practiced in southern Wisconsin ever since. He said over the last 10 years, ownership of veterinary clinics has changed dramatically.

Corporations are interested in veterinary practices, he said, because the business was relatively recession-proof during the 2008 financial crisis. Pet owners today consider their “fur babies” members of the family.

As a result, people spend more money for their pets’ care. For instance, the veterinary care and products market is expected to increase from $38.3 billion in 2023 to $39.1 billion in 2024, according to the American Pet Product Association.

Sometimes, patrons might be unaware of who owns their pet clinic. Mars Inc. —the owner of Snickers, Dove and Poptarts — also owns 3,000 vet clinics worldwide. Fortune called the company the biggest veterinary care provider in the country.

Howlett previously worked for a corporate veterinary clinic in Wisconsin. He said staff still had autonomy over the veterinary care, including decisions such as what drugs to prescribe or tests to recommend. But employees felt pressure from ownership to see an unsustainable amount of patients.

“There were quotas put on staff members to try to sell things (like) fecal tests,” he said. “Making staff feel more like they were salespeople as opposed to health care professionals.”

Dally and Howlett agree that employees working at corporate-owned veterinary clinics can have a limiting or difficult working environment, but still aim to give the best quality care.

The co-op model is a better fit for them, however. Dally worked closely with the UW Center for Cooperatives to establish the clinic. Although there are matters the employee-owners are still working out, things seem to be going well.

“I just am super excited to watch young people getting to be leaders of a group and decision makers and share with each other their ideas and ways of working out disagreements and having to compromise,” Dally said. “I’ve just seen the process works so well in so many ways.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.