A new book makes the case for why Wisconsin has been a crossroads for trailblazers, newsmakers and glass-ceiling breakers for decades.

Wisconsin author Dean Robbins’ new book “Wisconsin Idols: 100 Heroes Who Changed the State, the World, and Me” is a collection of essays about notable people who have a connection to Wisconsin, either because they lived in Wisconsin or had a significant experience while passing through.

“It’s been a lifelong obsession,” Robbins told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “Ever since I was little, I’ve had a pantheon of heroic figures that I’ve idolized; people with exceptional courage, integrity or vision. I’ve always wanted my heroes to be your heroes, and the best way to do that is through storytelling.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Robbins shared more about just a few of the exceptional characters in his book on “Wisconsin Today.”

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

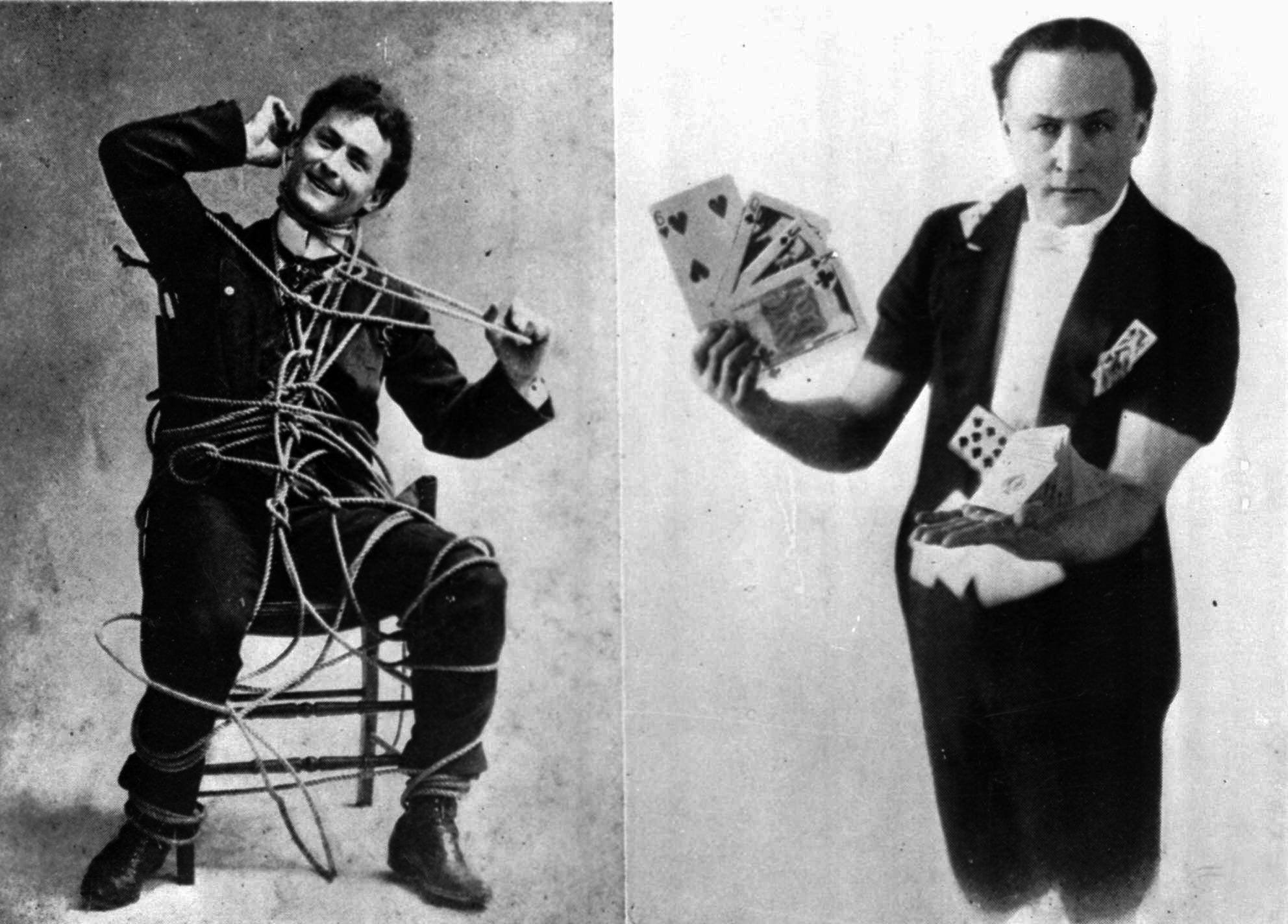

Kate Archer Kent: You’ve marveled at Harry Houdini since you were 7 years old. What was it about Houdini’s story that kept your attention from the time you were a child?

Dean Robbins: I started off idolizing superheroes like Superman. I would draw S’s on a piece of paper and tape them to my undershirt so that I could rip off my shirt and fly off to help anybody who was in trouble. When I got older, I realized that there were real people who were like superheroes, and Houdini was the first one I discovered.

I was watching an old movie called “Houdini” [starring] Tony Curtis at my grandparents’ house, and I couldn’t believe that this was a real person, not a made-up character like Superman or Batman. I would ask my sister to tie up my wrists and my ankles with bandanas so that I could wriggle out of them the way Houdini did.

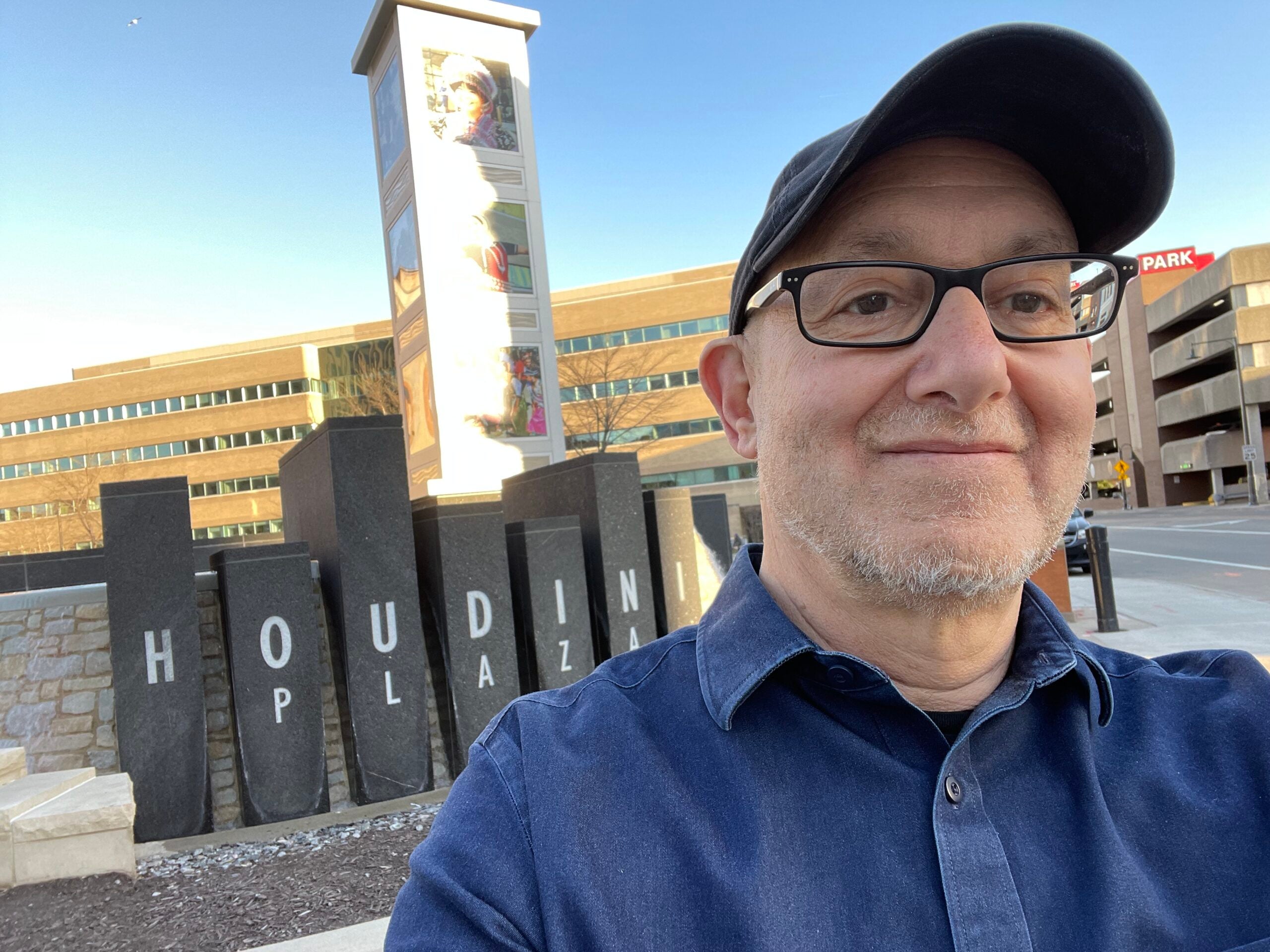

I knew that Houdini had grown up in Appleton. So as soon as I [moved to Wisconsin] in the ’80s, I made a beeline to Appleton to walk in his footsteps on College Avenue, look at the place where he lived with his parents and check out the local history museum that had a bunch of his locks, keys and straight jackets. Appleton does a good job of memorializing him. They’ve got plaques that mark the places where he had lived and where he had had significant experiences. There’s Houdini Plaza, which is built on the place where he lived, and there’s a gorgeous statue of him in a straight jacket twisting out of it that I just stood and gazed at for about probably 15 minutes. Houdini is a foundational hero for me.

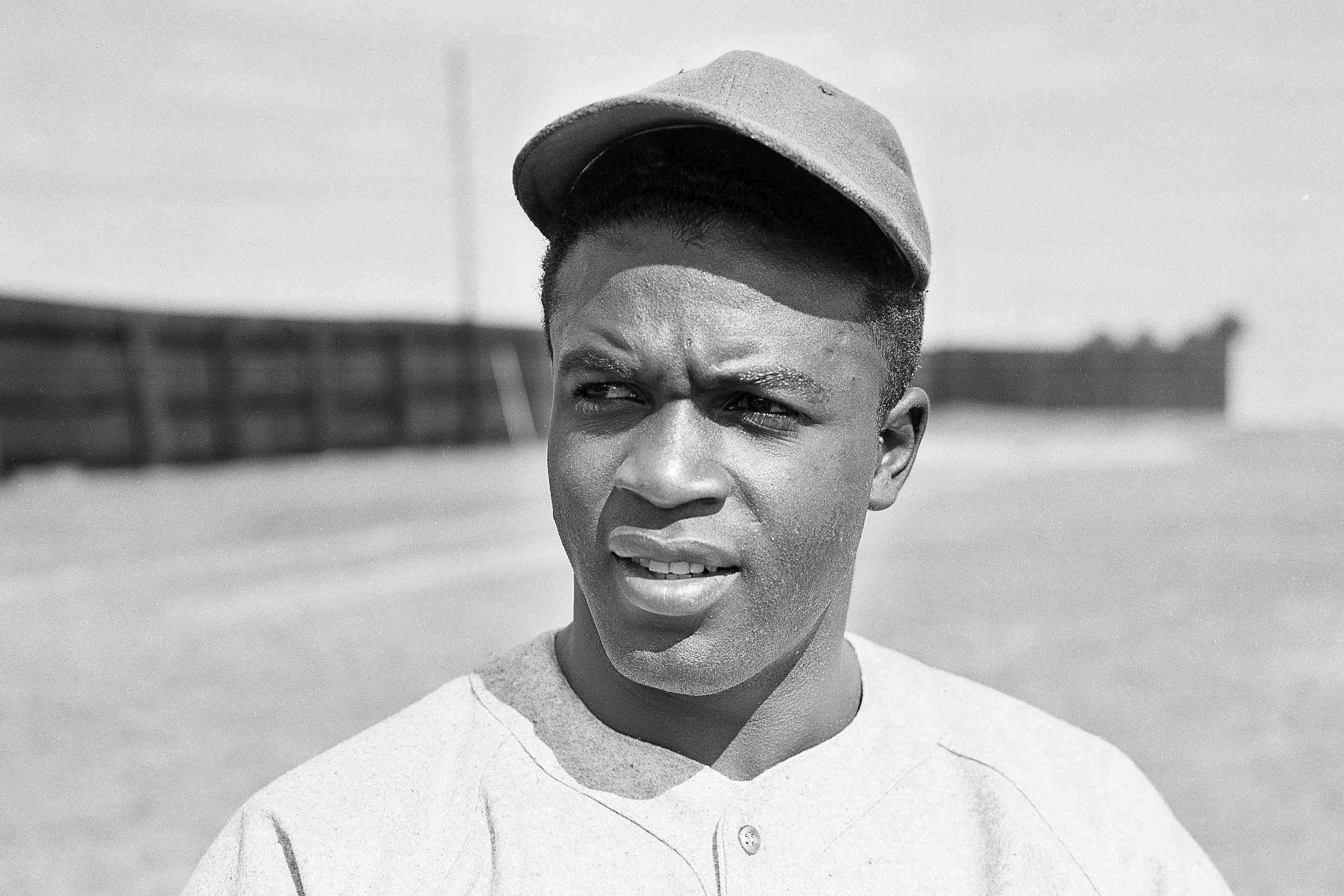

KAK: Why did you include Jackie Robinson in this book about Wisconsin?

DR: There was an 8-year-old white boy from Sheboygan named Ronnie Rabinowitz who wrote Jackie a fan letter, and Jackie wrote him back. Once, Ronnie and his father went to a game in Milwaukee between Jackie’s team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Milwaukee Braves. Ronnie called out from the stands to Jackie, saying, “Jackie, remember me? I’m Ronnie Rabinowitz!”

And Jackie called back, “Oh yeah, you wrote me a letter, and I wrote you back. Stay in touch!” And they began a lifelong pen pal correspondence. Jackie also helped Ronnie. He inspired him in so many ways. He would share his philosophy of personal integrity and racial harmony, and Ronnie considered it a formative experience in his life.

KAK: Turning now to “The Wizard of Oz,” which has a character who everyone probably remembers. It’s not one of the main four. Tell us about the famous Wisconsin connection to the movie.

DR: Meinhardt Raabe is an incredible character. He grew up in rural Farmington. He was a little person, and he was so isolated that he thought he was the only one like himself in the world. As he grew up, he went to the Chicago World’s Fair and discovered other little people who were working there. He was overjoyed to find that there were others like him, and he actually joined as a performer at the World’s Fair.

He was an extremely adventurous person who refused to recognize any limitations in his life. So when he graduated [from] college, he had courses in diction. He did a lot of public speaking, and when he heard that there were auditions for this movie called “The Wizard of Oz” and they needed little people, he made a beeline for Hollywood to try out.

There were nine speaking parts, and he was the Munchkin coroner who famously said that the Wicked Witch [of the East] wasn’t “merely dead,” but “really, most sincerely dead.” He was on screen for 13 seconds and he was famous for the rest of his life for this memorable appearance.

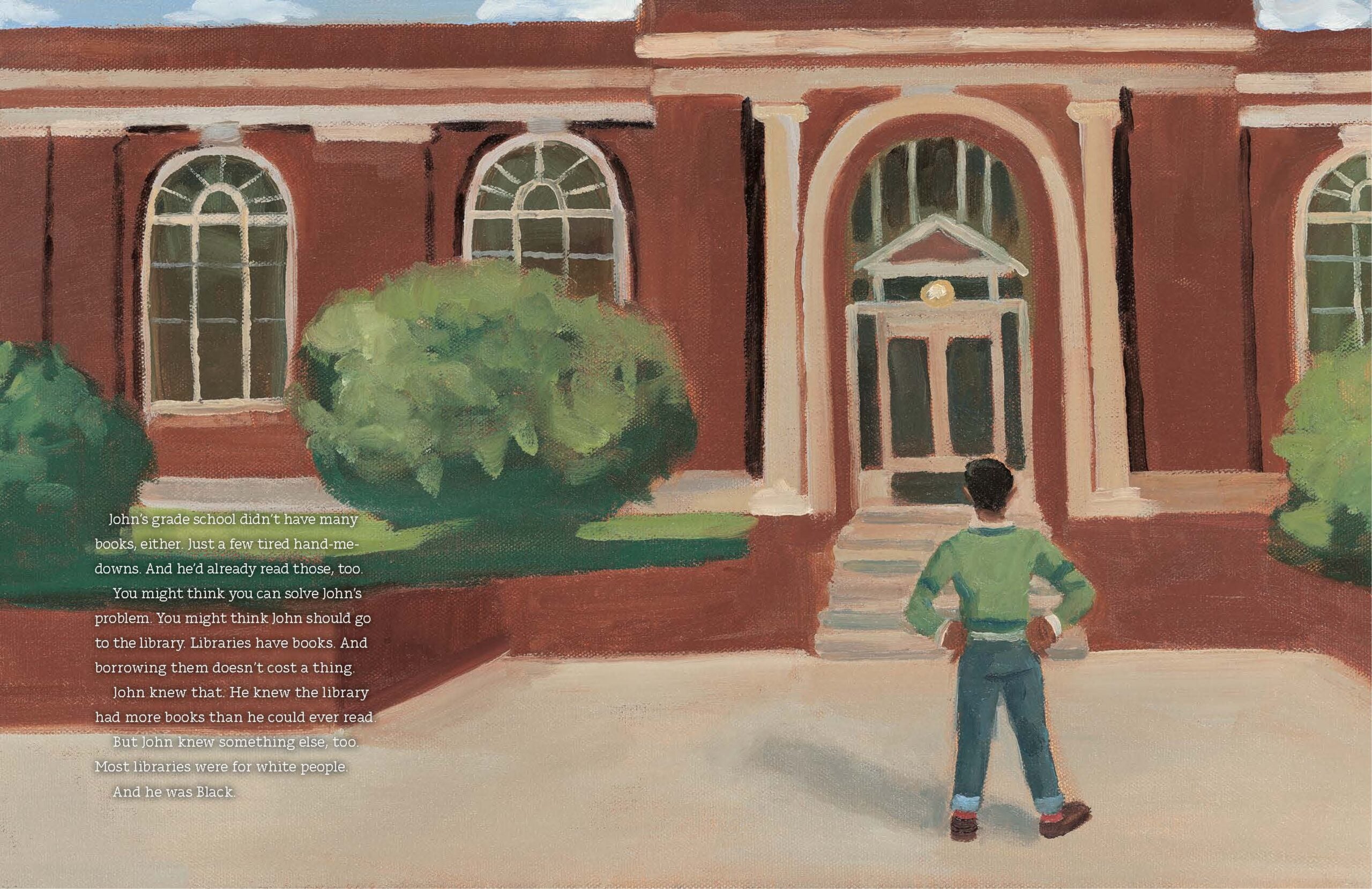

KAK: One of the most famous plays about the Jim Crow era, “A Raisin in the Sun,” was written by Lorraine Hansberry. She attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison for a time. Can you tell us more about Hansberry’s accomplishments and why you wanted to write about them?

DR: I think it’s a little-known fact that this great American playwright who wrote a classic document of the African American experience has a connection to Wisconsin.

She went to the University of Wisconsin for a couple of years in the 1940s. This would have been an unconventional choice at the time because a lot of Black college students went to historically Black colleges in the South. She chose to go north from Chicago for some reason to the University of Wisconsin.

She drifted for a little while, until she happened to go to a play put on by the University of Wisconsin theater department called “Juno and the Paycock” by Seán O’Casey, and she was utterly transfixed by this story of workaday Irish people speaking in their natural poetry. The playwright didn’t bother to clean up their messes or idealize them in any way. This became the inspiration for her to write her own play, which took a similar approach to African Americans and became “A Raisin in the Sun.”

Listen to and read more stories about Wisconsin’s pop culture icons from Dean Robbins on WPR’s “Wisconsin Life.”