Peggy West-Schroder describes herself as a “political nerd.”

So when she was convicted of a felony in Wisconsin several years ago, she faced one of the worst punishments she could imagine: She lost her right to vote.

“For me, that really was my punishment — not being able to vote,” West-Schroder recently told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “I didn’t mind checking in with my probation agent, paying the fees, I was fine with all of that. But it really did hurt me that I had to sit out the governor’s election.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The Associated Press estimates that a little under 5 million people are eligible to vote in Wisconsin, and the Wisconsin Elections Commission reports that about 3.5 million people are registered to vote in the state as of Oct. 1.

But people who are convicted of felonies lose their right to vote, at least for a while. The Sentencing Project, which advocates for criminal justice reform, estimates that 65,000 people in Wisconsin have lost the right to vote due to felony convictions.

“Wisconsin Today” spoke with three people who lost — and then regained — the right to vote about how it affected them and what reforms they would like to see.

Kelly Mahoney works for EXPO of Wisconsin, which stands for Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing. The group strives to end mass incarceration and restore formerly incarcerated people to full participation in community life.

Mahoney grew up in a union family where voting was extremely important. Losing the right was painful.

“I would go with my parents to the voting booth,” she said. “It was extremely important, and it meant a lot to me. So for me not to be able to do that with my daughter was very difficult for me. Not being able to vote on referendums for her school was also very difficult for me.”

“You feel less of a citizen,” she added. “Part of being a citizen is your right to vote, and so the message that I was receiving was that I was less than.”

Nycki Wallsch is a peer support mentor with WE ADAPT in Eau Claire. She said she never had interest in voting until after she lost the right. But when she started working with advocacy groups, she saw the importance.

“A woman that’s been abused — we think that our voice doesn’t matter,” she said.

“I started to see the power that the vote has,” she later said. “I started to see how hard other people were fighting to get their rights back.”

In Wisconsin, people can have their voting rights restored once they have completed their sentences, including terms of extended supervision, parole or probation.

The state Department of Corrections sends people a letter once they have completed their sentence — “getting off paper” — but the process can be unclear. Mahoney said she worked with a woman who had fully completed her sentence and went to vote, only to have an election clerk threaten the woman with another felony charge if she tried to vote.

People are also forbidden from circulating nominating petitions while they’re “on paper.” But they can do other things to get involved, West-Schroder said, including canvassing for candidates and driving people to the polls.

“There’s still a lot of ways to get involved, even though you can’t physically fill out a ballot,” said West-Schroder, who works for Saint Vincent De Paul’s re-entry program in Milwaukee.

Voting rights for people convicted of felonies vary widely by state. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that in 10 states, people indefinitely lose their right to vote for some crimes, unless they are pardoned or take some action to restore them.

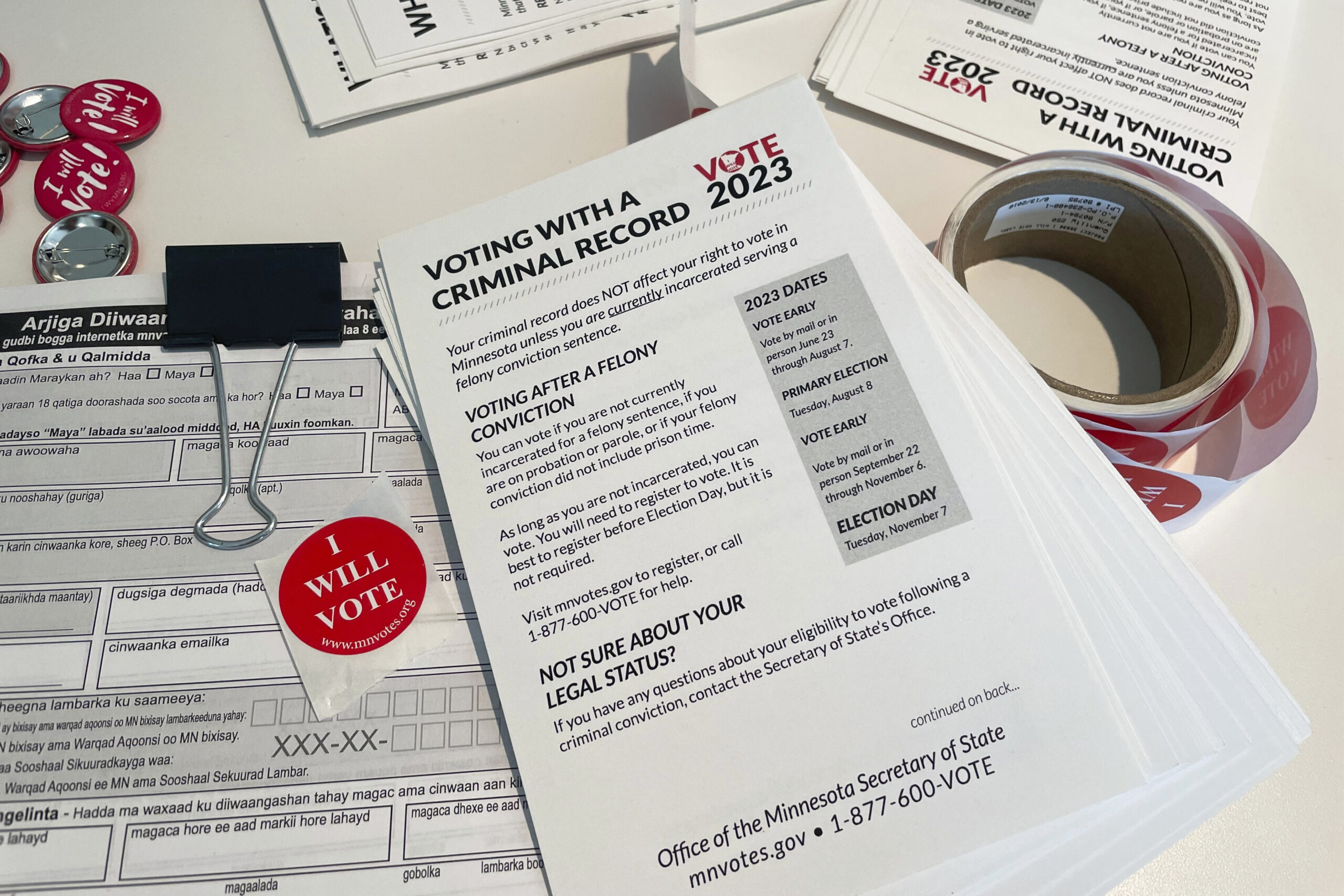

But in Washington, D.C., Maine and Vermont, people never lose their voting rights, even while they are incarcerated. In Minnesota, people can vote once they are released from prison, regardless of whether they’re under supervision.

West-Schroder had her voting rights restored in 2020, just in time for the previous presidential election. She would like to see Wisconsin allow people with felonies to vote while they’re incarcerated or on extended supervision.

“I’m a person of color, and I know that especially in our communities, we’re conditioned to believe that our vote doesn’t matter — the reason is because people want us to believe that,” she said. “And by saying, ‘No, you can’t vote because you are currently on probation or parole or because you are in prison,’ those are just ways of suppressing the vote and keeping communities of color from stepping up and people running for office and really creating generational voting, which is really what my goal in life is, at least within my own family.”