While dozens of other states have line-item vetoes, Wisconsin stands alone when it comes to the power it gives its governors through what’s known as the partial veto. Now, it’s up to the Wisconsin Supreme Court to decide whether it stays that way.

The state’s partial veto dates back to 1930, when concerns about state lawmakers adding multiple appropriation and policy items into what are known as omnibus bills came to a head. The Wisconsin Constitution was amended to give more power to governors to reject those items, one by one.

“Appropriation bills may be approved in whole or in part by the governor, and the part approved shall become law,” the new amendment read.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

According to a study by the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, proponents believed governors needed a check on the new budgeting process. But opponents worried giving governors more veto authority extended the already broad powers of the executive branch.

When he was campaigning for governor, Phillip La Follette said the proposal to expand veto powers “smack[ed] of dictatorship.” The amendment was approved by around 62 percent of voters in 1930, and after he was elected, La Follette became the first governor to use it.

Nine times, the Wisconsin Supreme Court has heard challenges to the partial veto. The case now pending before the Wisconsin Supreme Court will make it an even 10.

Evers used partial veto to extend school funding increase for 400 years

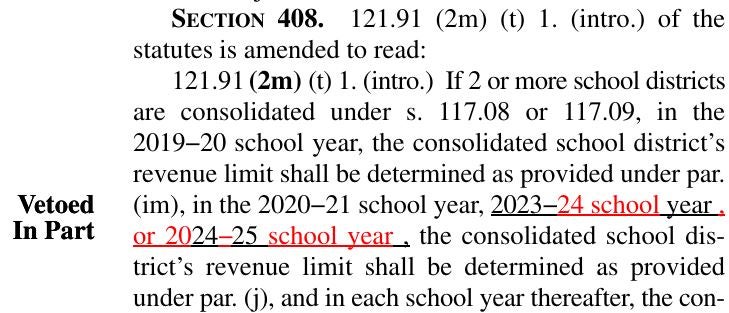

The latest challenge focuses on Gov. Tony Evers’ partial veto in the last state budget, which extended a school funding increase through the year 2425. It’s the latest of many attempts to restrict a veto power that a federal judge once described as “quirky.”

Evers’ partial veto last summer caught the Republican-controlled Legislature by surprise. By crossing out a 20 and a dash before he signed the state’s two-year budget, Evers authorized school districts to collect additional property taxes to fund a $325 per-pupil increase for more than 400 years. The Legislature intended the increase to expire in two years.

Republican lawmakers were outraged. The GOP-controlled Wisconsin Senate voted to override Evers’ veto, but the Assembly never followed suit.

The challenge the Wisconsin Supreme Court agreed to hear Monday, which was brought by taxpayers represented by the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce Litigation Center, alleges Evers’ veto violates the state’s constitution. The first legal briefs are due by July 16.

Democratic and Republican governors have used partial vetoes extensively

Evers’ latest veto received national attention, but he was hardly the first Wisconsin governor to push the limits of the unique power.

Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker struck individual digits from dates written in the 2017 state budget to change a one-year moratorium on school referendums aimed at raising taxes for energy efficiency projects into a 1,000-year moratorium. The Supreme Court’s former conservative majority threw out a challenge to Walker’s veto because it was filed too late.

Former Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle used his partial veto to combine parts of unrelated sentences in the 2005 budget to move more than $400 million from the state’s transportation fund into the general fund. That led to a constitutional amendment in 2008 at preventing future governors from using what became known as the “Frankenstein Veto.”

With his first state budget in 1987, former Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson partially struck phrases, digits, letters and word fragments, using what was known as the “Vanna White” veto, to create new sentences and fiscal figures. The Supreme Court upheld Thompson’s partial veto, but in 1990, voters approved a constitutional amendment specifying that governors cannot create new words by striking individual letters.

University of Wisconsin Law School State Democracy Research Initiative Attorney Bryna Godar told WPR governors have gotten creative with how they’ve used partial vetoes, “but we now have this very long standing practice that is really codified in state law.”

Godar said even the constitutional amendments aimed at restricting a governor’s partial veto powers were — in some way — a stamp of approval from the Legislature.

“They didn’t completely do away with this,” Godar said. “If people really wanted that, you could argue that they could have amended the constitution to completely do away with this type of partial veto.”

Godar said it’s possible that current lawmakers don’t want to restrict partial veto powers too much in case the current political power structure of the Legislature and Governor’s office switch in the future.

Until 2020, Supreme Court generally allowed partial vetoes to stand

For as long as Wisconsin has had a partial veto, there have been lawsuits about how governors have used it.

The first came in 1935 and challenged the governor’s partial veto of an emergency relief bill, which approved funds but struck provisions related to how the Legislature wanted the money to be spent. The court upheld the partial veto so long as the remaining language equates to “a complete, entire, and workable law.”

Future courts upheld partial vetoes in 1940, 1976, 1978, 1988, and 1995.

Things changed in 2020 when three of four partial vetoes by Evers in the 2019 state budget were struck down by the Supreme Court’s former conservative majority. But instead of a single majority opinion, the court issued what’s known as a fractured ruling. There were four opinions issued by justices that provided different tests for whether a partial veto can be constitutional.

“Those vetoes in that case were pretty in line with what governors from either party have done in prior decades,” Godar said. “They weren’t a significant departure from how this has been used in the past, but the court struck down three of them.”

But not having a “unified majority opinion” in the 2020 case, Godar said the court didn’t offer clear reasoning on how governors can use the partial veto in the future. But that could change in the latest case challenging Evers’ veto.

“I am really curious to see how the court rules in this case,” Godar said. “Because I think they will tell us a lot about what type of partial veto we will have going forward, and if it will continue to be this pretty broad, granular veto, or if it will be more based on subject matter.”

Looking at the big picture, Godar said the question is whether the legislative and executive branches are “striking the right balance” of power.

“And so, it is ultimately up to the Legislature and the people if they want to restrict it more significantly, which they could do in the future,” Godar said.

Meanwhile, Republican lawmakers are pushing for another constitutional amendment in reaction to Evers’ latest veto. Earlier this year, the Legislature passed a proposed amendment aimed at keeping future governors from using the partial veto pen to “create or increase or authorize the creation or increase of any tax or fee.”

Before the new language can be added to the constitution, the measure must pass the full Legislature during the next legislative session and be approved by voters in a statewide referendum.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.