Over the first three months after the coronavirus pandemic struck Wisconsin in March, only two days passed during which no Wisconsinites were announced to have died from the new disease wreaking havoc around the globe in 2020. One was May 17 and the other was June 8.

Wisconsin’s daily COVID-19 statistics stood out for another reason on that latter date. Not only were there no new deaths to report, but the Wisconsin Department of Health Services instead lowered the statewide death total by one.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The revision resulted from a fairly run-of-the-mill issue: A duplicate record caused a temporary miscount of deaths in Milwaukee County. Even so, this correction illustrates one of the many difficulties health officials in Wisconsin and elsewhere face as they track and report information about the lethal impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a complex public health crisis unfolding in a politically polarized age and socially fractured moment.

Official health data about COVID-19 has the power to inform public policy and attitudes toward the disease and the risks it presents. Chief among its impacts that particularly trouble healthcare professionals, policymakers and plenty of everyday people is its tendency to kill a disquieting number of those who are infected.

Wisconsin’s COVID-19 deaths data

The first two known COVID-19 deaths in Wisconsin were announced on March 19, 2020: A man in his 50s from Fond du Lac County and a man in his 90s from Ozaukee County. In the nearly three months between that date and June 11, the state Department of Health Services reported a total of 682 state residents are confirmed to have died from COVID-19.

Daily COVID-19 deaths in Wisconsin hovered above and below about 10 per day between early April through early June. The date with the highest number of deaths confirmed during this period was May 27, which saw 23 reported.

The disease has affected communities around the state to varying degrees, reflected in both the number of cases and deaths. In terms of mortality, 40 counties in the state had recorded at least one death due to the disease as of June 11.

Milwaukee County, the state’s most populous, has recorded far and away the most confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths in Wisconsin, accounting for nearly half of each. These numbers are not simply a reflection of Milwaukee’s size: The county also leads the state in deaths per capita by a considerable degree.

While these figures help identify where Wisconsinites are dying from COVID-19, they don’t necessarily assist with understanding the risk of death for individuals or in communities. Ongoing efforts by scientists and public health officials to analyze and supplement these data are aimed at providing a clearer understanding of this risk, and how it varies across populations. These efforts must begin with identifying as many COVID-19 infections and deaths as possible, an exceptionally difficult task for a new disease with such diverse symptoms and outcomes.

Identifying infections

Five months after authorities in Wuhan, China reported the first death from COVID-19 on Jan. 11, more than 400,000 people worldwide are confirmed to have died from the disease. That figure amounts to more than 5% of the roughly 7.2 million confirmed infections around the globe. Within Wisconsin, about 3% of the more than 21,000 people diagnosed with COVID-19 in Wisconsin between Feb. 5 and June 11 have died.

These statistics are known as case fatality rates. While based on real data reported by labs, doctors and medical examiners, these rates tell an incomplete story about COVID-19’s deadly burden on communities. The disease’s true fatality rate, what epidemiologists refer to as its infection fatality rate, is almost certainly substantially lower.

A large part of this difference lies in an inability of health authorities to identify every person who becomes infected with COVID-19, a disease with a spectrum of symptoms that range from life-threatening to very mild or even unnoticeable. Compounding this problem during the pandemic’s early days was a severe limitation on the availability of testing for COVID-19, meaning the cases that were detected tended to be more severe.

“That at first made any kind of case fatality rate, like [the one] in Wisconsin for instance, highly skewed toward those who were likely to die,” said Amanda Simanek, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Public Health.

Since mid-April, when Wisconsin relaxed criteria for COVID-19 testing beyond seriously ill patients, expanded capacity has likely captured a growing portion of COVID-19 infections in the state, including many people with milder symptoms. Over that same time, the state’s case fatality rate has steadily fallen from above 5% in mid-April to just over 3% on June 11. Simanek said she would expect to see the case fatality rate drop further if testing continues to expand.

This dynamic — broader testing revealing a lower fatality rate — is apparent at the local level as well.

For instance, of the 64 patients who had been hospitalized for COVID-19 at Bellin Hospital in Green Bay by early June, six had died, according to Dr. Paul Casey, an emergency room physician at Bellin who led the development of its COVID-19 treatment strategy. This would make for a case fatality rate of nearly 10%, a high figure that reflects the peril the disease presents among patients who are hospitalized.

However, by early June, Bellin Health System had screened some 10,000 people for COVID-19, including many without symptoms as part of a targeted testing operation following outbreaks at multiple meatpacking plants in the area. In all, Bellin’s testing identified 2,718 individuals with infections, according to Casey.

That number made the case fatality rate among the patients the health system tested a much lower 0.2%. (Meanwhile, state data showed Brown County’s overall case fatality rate was significantly higher, at 2%, as of June 11).

“I think we’re homing in on the actual death rate,” Casey said of Bellin’s figures, noting that a significant number of cases the system has detected were asymptomatic individuals associated with the meatpacking outbreaks.

“To determine an accurate death rate, you have to have an accurate number of patients who actually have the disease,” he said. “And the fact that so many patients are asymptomatic or don’t get tested means that the denominator is far higher than what we probably thought early on.”

Figuring out the denominator, in this case the true infection rate of a disease, is a fundamental aspect of epidemiology.

Estimating more infections

Exactly how high the true denominator of COVID-19 infections is remains a key question for epidemiologists studying the disease. A growing number of scientific studies are attempting to offer potential answers for this question, at least at local and regional levels.

These studies have depended on tests that detect the presence of blood proteins called antibodies that are central to the immune system’s response to all sorts of pathogens like the virus that causes COVID-19, known as SARS-CoV-2. Unlike the virus itself, which is what COVID-19 tests detect in symptomatic patients, antibodies stick around after an infection and for many pathogens provide some level of immunity against future infection. Whether this is the case with COVID-19 is yet another unresolved question surrounding the disease.

Either way, the presence of antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 could indicate an individual was previously infected. Studies based on widespread antibody testing, such as ones in New York and California, have estimated infection rates in some localities from anywhere between a few percent to as high as 20%.

However, a flood of COVID-19 antibody tests have hit the market in the United States, and only a handful have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and produce a relatively low number of false-positive results, according to Simanek. And even the better tests used in many scientific studies to-date are likely to over-detect antibodies in most populations at this point in the pandemic, she said.

“In a population where the prevalence [of infection] is fairly low, you’re going to have a lot of false positives,” she said.

Even the best tests produce false positives sometimes. In a population with relatively few people with infections and the antibodies associated with them, there are many more opportunities for antibody tests to produce false positives than in a population where infection rates are relatively high. As a result, health officials in Wisconsin who are tracking antibody test results around the state have said they are being cautious about interpreting the data they’re collecting, which as of early June had not been made publicly available.

And there are even more uncertainties to account for as scientists seek to pinpoint the risk of death from COVID-19.

Determining deaths

The number of COVID-19 infections in a community or region provides only one half of the information needed to figure out the disease’s true death rate. The other half of the equation are the deaths themselves.

In theory, this number should be easier to track than infections, and official death figures are likely to be more accurate than case counts. After all, deaths are unambiguous, and creating records of when, where and how people die is a standard function of civil society.

Indeed, Wisconsin’s official COVID-19 death statistics are largely composed of clear-cut instances in which a patient diagnosed with the disease dies in a hospital or other healthcare setting such as a nursing home. In these cases, a doctor often confirms the death as caused by acute respiratory failure or another fatal outcome triggered by COVID-19 infection. This process is known as “coding” the death, and doctors use guidelines developed by the World Health Organization to determine whether and how to code a death as caused by COVID-19.

Deaths in a hospital or other treatment setting are usually easily attributable to COVID-19, even when testing fails to confirm the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, according to Dr. Paul Casey, the ER doctor at Green Bay’s Bellin Hospital.

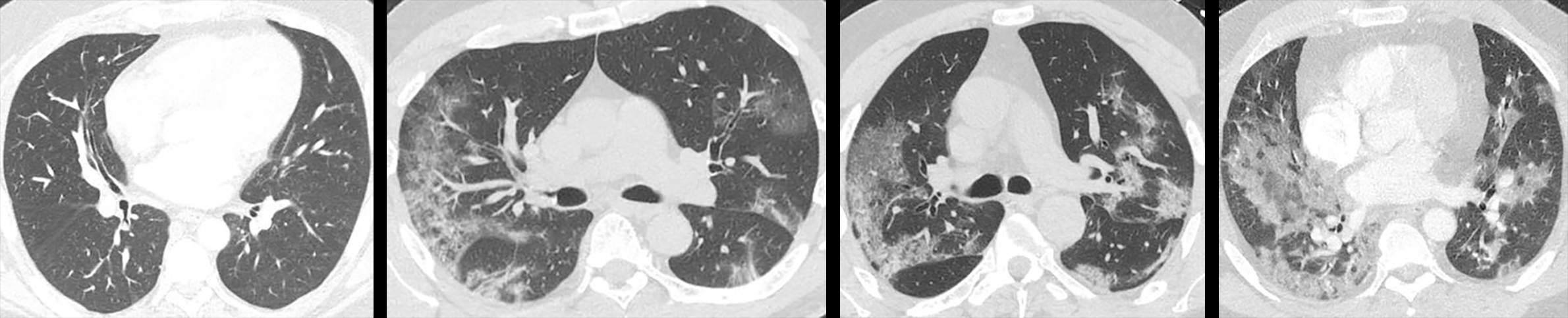

That’s because there are clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in patients with serious disease that Casey described as unique. The most characteristic of these symptoms are revealed via a CT scan of the lungs, he said. They’re called “ground-glass opacities” and appear as round, mottled white areas within the lungs.

“I’ve been practicing medicine for 30 years, and I have never seen anything that looks like COVID pneumonia on a CT scan,” Casey said. One of the six patients who have died from COVID-19 at Bellin was diagnosed with the disease via CT imaging, he said, noting that the patient tested negative three times before dying.

“Sometimes, for whatever reason, the nasopharyngeal swab can be negative,” Casey said. “But if everything fits, we have the discretion as a clinician to say ‘This patient had COVID pneumonia.’”

Casey added that conspiratorial claims that doctors are being pressured to attribute non-COVID-19 deaths to COVID-19 in an effort to gain funding or inflate the death toll are “absolute B.S.”

“You can see from these [WHO] guidelines it’s very clear that even if somebody tests positive but dies from another cause, you don’t list COVID as the cause of death,” he said.

While patients with clear clinical symptoms who die in healthcare settings represent the majority of deaths attributed to COVID-19 in Wisconsin, that’s not the case for all people who succumb to the disease in the state. When someone dies at home or another non-healthcare setting and is known to have had symptoms aligning with COVID-19 or a known exposure to the disease, the local medical examiner is usually called in to determine whether the death was due to COVID-19.

It is common in these cases for a medical examiner to order a post-mortem COVID-19 test. That’s according to the medical examiner offices in Milwaukee, Racine and Dane counties. In early June, these counties had the first, second and sixth highest COVID-19 death tolls in the state, respectively.

The Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s Office was ordering a post-mortem COVID-19 test in a home death investigation roughly once per day through most of April and May, according to Karen Domagalski, its operations manager. She said COVID-19 investigations had slowed somewhat in the county in early June and that a majority of post-mortem tests over the whole period had come back negative.

Just to the south, Racine County Medical Examiner Michael Payne said his office had only investigated a handful of home deaths possibly caused by COVID-19, and noted post-mortem testing revealed infections in only a few.

Meanwhile, Barry Irmen, director of operations for the Dane County Medical Examiner, said the office was “exceptionally busy” in early June, but added that most of its death investigations were not related to COVID-19. He estimated the office was ordering a post-mortem COVID-19 test about once daily throughout the spring.

All three said their offices would only declare a death as caused by COVID-19 if a post-mortem test came back positive.

“If we have a negative post-mortem test, COVID should not appear on the death certificate,” said Irmen.

Payne went further and said he declared one death as not related toCOVID-19 even after test results came back positive. The case involved an individual who died under hospice care and had a known exposure to COVID-19, Payne said, triggering a post-mortem test. Despite the positive result, Payne said the individual’s physician was adamant they had died from end-stage lung cancer.

“I’m not an M.D., so I defer to those folks,” he said.

The search for missing deaths

Even thorough investigations are liable to miss some COVID-19 deaths since they rely on the use of post-mortem tests that are not perfect. To fill in the gaps, epidemiologists are analyzing overall death rates to discern any noticeable spike in deaths that may be either directly or indirectly attributable to COVID-19.

These analyses aimed at “excess deaths” have shown that in many regions of the U.S., official COVID-19 statistics are likely undercounting the disease’s mortality impact to a significant degree.

Jennifer Dowd is an associate professor of demography and population health at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Dowd has collaborated with colleagues in Wisconsin on some COVID-19-related work, including Amanda Simanek at UW-Milwaukee and Malia Jones, co-director of the health geography research program at the University of Wisconsin’s Applied Population Lab. (Jones is a WisContext contributor.)

Dowd said looking at excess death rates can help scientists and policymakers grasp a fuller picture of the pandemic’s total effect on deaths, including those that may not be the result of a COVID-19 infection but may be attributable to other factors.

“We do believe there’s a portion of people [who have died] who either the hospitals were overwhelmed and didn’t treat them, or were people who didn’t seek out care because they were worried about going to the hospitals,” Dowd said. “It’s going to be very hard to separate those out from people who had an underlying health condition but also had COVID that wasn’t detected and died at home.”

That’s why, pending more specific data, Dowd said analyses should focus on any bump in total deaths.

To that end, provisional mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics show a bump in total deaths in Wisconsin during the spring of 2020 compared every year between 2016 and 2019.

Some of this rise in deaths can likely be accounted for by those deaths in 2020 already attributed to COVID-19. However, the total number of deaths recorded in April in particular suggests some COVID-29 deaths may have been missed by health authorities, or there were more deaths indirectly related to the pandemic, or some combination of each.

Indeed, anecdotal evidence abounds that the deaths of some Wisconsinites who have likely perished from COVID-19 aren’t being captured in official statistics, as an April 30 investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel concluded.

The report detailed how a breakdown in communication in Ozaukee County meant a probable COVID-19 death there wasn’t communicated to the local health department, where it would have been forwarded to the state. It quoted the local health officer, Kirsten Johnson, as stating her belief that hospitals and other facilities were failing to report some COVID-19 deaths — even those with positive test results.

On the other hand, a data analysis by the New York Times used CDC mortality data from past years to model the number of deaths that could be expected in Wisconsin and every state over the first three months of the pandemic. As of June 10, this model showed that Wisconsin experienced only about 100 more deaths than would have been expected so far in 2020.

At a more local level, as of May 21, some 1,309 Milwaukee residents had died from natural causes outside of a healthcare setting, according to city of Milwaukee Health Department Commissioner Jeanette Kowalik. That’s compared to 912 deaths from natural causes over the same period in 2019. The 2020 figure included 246 deaths directly attributed to COVID-19, according to Kowalik.

Those confirmed COVID-19 deaths accounted for only a little more than half of the increase in natural deaths in Milwaukee over 2019.

Dowd urged caution in interpreting excess mortality data, especially at an early point in the pandemic while data continues to stream in and has yet to be verified. She also said lockdowns, such as Wisconsin’s nearly two-month-long stay-at-home order, may have temporarily reduced some other types of deaths, such as those that result from automobile collisions.

“It will be hard to tease this stuff out,” she said.

Determinants of death

Discussions about the overall risk of dying from COVID-19 are incomplete without acknowledging one bit of extremely clear evidence, said Amanda Simanek, the UW-Milwaukee epidemiologist: The risk of serious complications and death increases substantially with age, as well as with some pre-existing health conditions.

“It’s obvious that age is a huge determinant of death [from COVID-19]”, Simanek said.

This fact is borne out by Wisconsin’s official COVID-19 statistics. While people over 60 make up only 20% of the state’s confirmed and probable cases, this age group accounts for 87% of deaths attributed to the disease in the state as of June 11.

Growing scientific evidence is also showing that chronic diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disease also increase the risk of severe complications and death due to COVID-19.

Simanek, whose research includes the effects of health disparities, said it cannot be ignored that racial and ethnic minorities are succumbing to COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates, a dynamic that is likely influenced by higher rates of chronic illnesses and other health disparities.

In the end, Simanek said it would be some time before the disease’s full impact on mortality is clear. In the meantime, trying to assess datapoints like the case fatality rate would remain a “moving target,” she added, especially as testing continues to expand and treatments for the disease improve.

“The best way we can estimate the fatality rate is when this is over,” she said.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.