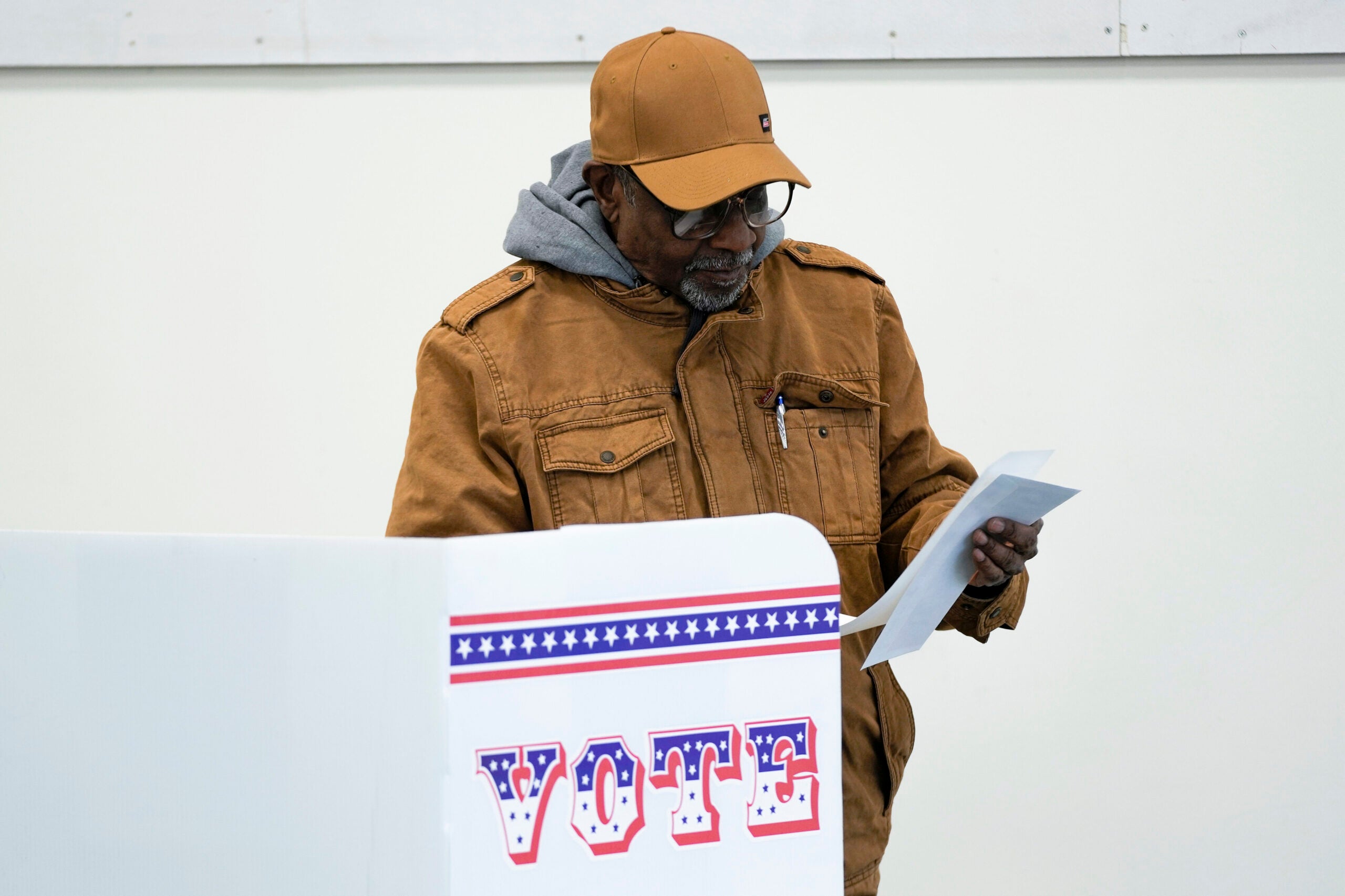

As jurisdictions around the country enact new approaches to casting ballots, two opposing proposals in the Wisconsin state Legislature take aim at one idea: ranked choice voting.

That’s a process by which voters rank candidates in order of preference. As lower vote-getters are eliminated, their votes are redistributed to the next-preferred candidates, in what amounts to a series of run-offs until one final candidate emerges.

Supporters of this process say it allows political minorities to still get a say, discouraging hyperpolarization. Opponents say it’s confusing and slows the gears of democracy.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

That opposition fuels a proposed constitutional amendment to ban the practice in Wisconsin. The GOP-led initiative would mean no Wisconsin election could utilize the process, and more broadly bars voters from voting for candidates of multiple political parties in partisan primaries.

While there’s no push for ranked choice voting as it exists in Maine or New York City, a bipartisan bill would bring one element of that process to Wisconsin. Deemed Final Five voting, the proposal would allow the top five vote-getters of any party in a Congressional primary to continue to the general election. During the general election, Wisconsin voters would go through the ranking process with those five candidates.

The idea, said Sarah Eskrich, the executive director of Democracy Found, which advocates for Final Five voting in Wisconsin, is to ensure greater accountability among elected officials.

She argues that a polarized electorate leaves many lawmakers accountable only to the most extreme elements of their base, and therefore not incentivized to moderate their positions, appeal to broad groups, or work on policies that would impact the most people.

“Congress can’t get anything done, and there’s no accountability for that from the electorate, because so many of our elections are decided in the primaries,” she said.

Under Final Five, a general election wouldn’t necessarily have one Democrat and one Republican. Instead, voters would choose among five candidates who could represent a range of policies among one or several parties. Eskrich argues that can promote real competition even in safe seats, forcing candidates to modulate their positions, rather than adopting the most extreme positions that appeal to highly motivated primary voters.

“In certain solidly red seats, or solidly blue seats, you might see multiple Republicans or multiple Democrats making it into the general election,” she said. “So that is what shifts the electoral competition from the primary to the general election, because all of a sudden, the votes of the general electorate – even in traditionally safe seats – start to matter, because they have real choices.”

The Republican co-sponsors of the anti-ranked choice voting amendment say that bringing a new way of voting to the state undermines already fragile trust in elections.

“Final five and ranked choice voting have proven disastrous for elections nationwide, causing prolonged result announcements when trust in election outcomes is already fragile,” Rep. Ty Bodden, R-Hilbert, said in a statement.

Opposing solutions to improving voter confidence

A mix of Republican and Democratic lawmakers back the Final Five proposal. It’s different from traditional ranked choice voting because it limits the number of candidates and only uses the ranking process in the general election, said Eskrich.

In theory, this provides more choices to voters even in safely red or safely blue districts, she said, so that political minorities don’t feel that their votes don’t matter.

The Wisconsin proposal would only apply to U.S. Congressional races, so it would not address how Wisconsinites vote for their statewide representation in the Assembly or Senate. It could help move the gears of Congress more effectively, Eskrich said, because representatives would be accountable to more people.

“When gridlock is more politically profitable than actually solving problems, it’s a pretty disappointing place to be,” she said. “And you see that in our public approval ratings for Congress. People are not satisfied.”

Congress’ approval rating is about 13 percent, according to Gallup polling.

But that won’t be solved by changes to voting practices, said Jason Snead, executive director of the Honest Elections Project, which advocates against ranked choice-style processes. Rather, he argued, introducing a new way of casting a ballot – different from how Americans are trained to vote from the time they are 18 – introduces confusion and sows mistrust.

Voters “want clear rules that are followed and adhered to from the beginning of an election to the end. They want a quick and accurate election results. And they want to clearly understand the way that the system operated,” he said. “I think that’s incredibly corrosive for public trust and public confidence in our election system. So at a time when people were saying they want clear outcomes, ranked choice voting is just turning elections into a black box.”

Snead argued that ranked choice voting has led to confusion and logjams in other jurisdictions that have adopted similar processes. A county in Northern Virginia stopped using the system for their general election this fall, after using it in the spring primary. The outcome of New York City’s 2021 mayoral race, the city’s first attempt at using ranked-choice, took weeks to determine.

“You’re going to ultimately corrode confidence in elections, and that’s going to dissuade people from voting,” he said.

Changing voting processes is also costly, he said. Ballots would be printed differently, and voter education and outreach projects would be necessary to ensure that people know how to cast their ballots.

The Final Five proposal received a hearing in early December. It’s unclear whether it will move forward for a vote in the Legislature.

The constitutional amendment has been referred to the senate elections committee. As a proposed change to the state constitution, it would need to be approved by two consecutive sessions of the Legislature, and then receive voter approval. That means it could not go into effect for the upcoming election cycle.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.