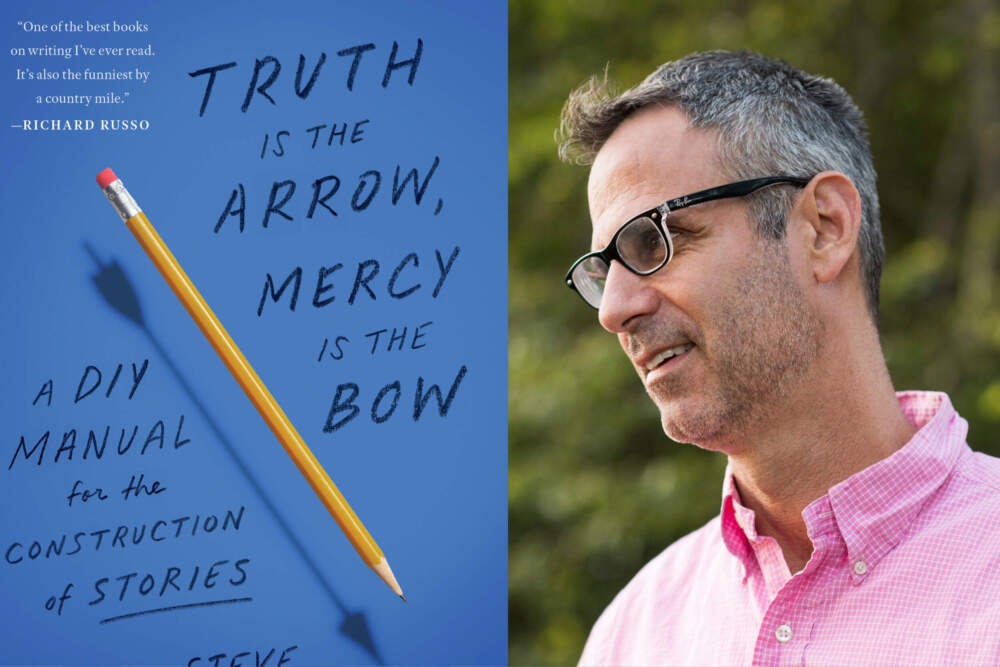

At first, we thought, “just what the world needs, another ‘how to’ book.” Then we read author Steve Almond’s “Truth is the Arrow Mercy is the Bow: A Manual for the Construction of Stories.”

It is an entertaining and informative book on writing that is also a great read. WPR’s “BETA” visited Almond to hear his thoughts on creating this superior writing guide.

To begin with, we wondered what Almond meant by the title of his book.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“For 30 years,” he told us, “I’ve been saying to students, ‘You’re only going to be able to be as truthful as you are merciful.’ That is, you have to be going in search of forgiving and understanding everybody. Because otherwise, you’re going to internally, unconsciously feel guilty about seizing control by telling the story.”

It took Almond 30 years of writing failure and success to find the words he thought could finally aid aspiring scribes in finding their way as writers. Almond’s conclusion is that rejection is the way forward.

“Rejection and failure are baked into the process. It’s not the enemy; it’s what you learn from. If you can outlast your doubt, you realize, oh, all those failed novels I wrote over 30 years were helping me understand the mistakes I was making and correct them,” he said. “It took me a long time because I’m a slow learner, but if I can sort of gather up the benefits of some of those mistakes I’ve made and present them to writers earlier in their careers, maybe they won’t take as long as I did.”

Decision fatigue

In his book, Almond says that writing is decision-making — nothing more and nothing less. You must decide what word to use, where to place the comma, how to shape the paragraph. We wondered if all that decision fatigue might be the hardest thing about writing.

“Yeah, that’s it.” He admits. “That’s an interesting phrase: decision fatigue. It’s a very understanding way of describing when people feel blocked or burnt out. I have this piece, ‘Writer’s Block’ — a love story — where I’m trying to tell people that we’re blocked all the time. “Let’s stop treating it like it’s the Black Plague and hiding it away as some great source of shame. We are constantly blocked.”

“I can be hard at work on a novel, as I was for years, typing words, making decisions, and pushing the character through some kind of plot,” he added. “But I’m still blocked because I don’t know that character’s inner life, and I don’t truly love them yet. I’m not ready to see them into their danger and see them through it.”

Indeed, Almond spends an entire chapter on writer’s block. In it, he says writer’s block is a negative feedback loop.

“Because that’s really what the reader’s picking up on. It’s not the subject you’re writing about; it’s the quality of attention, which is a sublimation of the ego.”

Steve Almond

“You feel your decision-making is doomed, so you shut yourself down. In other words, you can’t even get to the keyboard because you’ve already failed before you get there, which makes you feel like more of a failure because you couldn’t get to the keyboard,” Almond said. “And so one of the solutions I suggest to writers from my own experience is just to set the bar low because I’ve been telling myself a dumb, destructive story. You have to write a great big novel, or you’re not a writer.”

“That made me ask the question, what should I be writing? Instead of a much more helpful question, what can I write?” he said. “What will get me to the keyboard? What excites me? What gets my attention away from my doubt, unhappiness, and insecurity and into the world? Because that’s really what the reader’s picking up on. It’s not the subject you’re writing about; it’s the quality of attention, which is a sublimation of the ego.”

Almond took his own advice and wrote a book about something that excited him — and the floodgates opened.

“For me,” he said, “that was stumbling into a chocolate factory because I’m a lifelong candy freak and starting to connect to that feeling of, oh my God, they’re beautiful marshmallow bunnies marching down this conveyor belt being enrobed in chocolate and vats of caramel bubbling.”

“That was what brought me alive,” Almond added. “And even though I felt silly for writing a piece of pop culture ephemera at the time — whatever, you know, my snotty literary identity would say about that. What was happening was that I was reconnecting my curiosity and humility and having a ravenous desire to experience the world.”