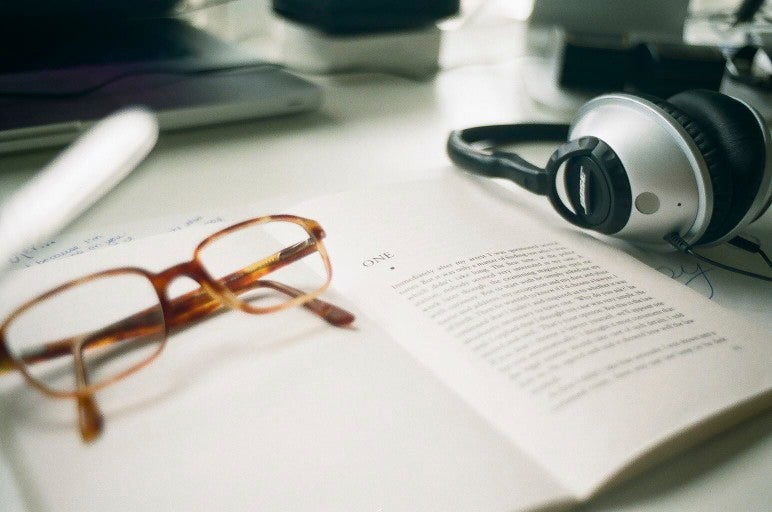

Whether you’re Team Read or Team Audiobook, there’s no reason to snub the other side, says Daniel Willingham, a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia.

That’s because reading a book isn’t any better than listening to it, he said, revisiting points he made in a New York Times piece, “Is Listening to a Book the Same Thing as Reading it?”

“I say don’t feel a little bit ashamed,” Willingham said. “Fly your audiobook flag proudly.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Reading and listening both result in comprehension, which the brain accomplishes by translating written or heard words into words in the mind — a process called decoding. Research has proven this, Willingham said, pointing to a study that saw participants score equally as well on comparable tests based on written and verbal materials.

“Once you’ve identified the words (whether by listening or reading), the same mental process comprehends the sentences and paragraphs they form,” Willingham wrote in the Times piece.

Brains interpret written and spoken information in the same way because humans haven’t had enough time to evolve a strategy to differentiate the two. Writing is younger than 6,000 years old, Willingham wrote.

So, in short, listening to audiobooks isn’t “cheating” as some die-hard readers might purport.

This indictment of cheating could be because audiobook readers take the work out of deciphering intonations, sarcasm and other language tools that convey meaning. While some might consider that lazy reading, Willingham suggests a different perspective.

“Other people feel like the person who’s reading this book can really be an artist in their own right, and they’re adding their interpretation to the author’s words, and I’m going to be the beneficiary of that,” he said.

Willingham, who calls himself “a booster of reading,” said the suggestion that audiobook users are cheating could also be because people who read have to designate time and forgo other activities to do it. There’s truth to that, Willingham said. Multitaskers might not be devoting full attention to the book in the same way someone who is reading it would.

“But I think hurling accusations amongst readers is not a civil war we really want to start,” he said. “I mean, reading is in enough trouble; people who enjoy reading shouldn’t be fighting with one another.”

Audiobooks have surged in popularity in recent years and the rise continues. According to the Association of American Publishers, the first three months of 2018 saw nearly $100 million in downloaded audio, an increase of about 32 percent from the same period a year prior.

And apart from allowing readers to multitask, audiobooks give others a chance to enjoy a narrative, for example some people who have dyslexia and find decoding difficult.

“But once the words are in the mind, they don’t have a problem with language,” he said. “So, allowing them access to audiobooks allows them to bypass the problem that they’ve got and get access to books the way (others) have access to books.”

If kids aren’t enjoying the decoding process, audiobooks might be a way into reading, Willingham said, noting that he often advises parents to play audiobooks in the car.

“In the car, children are sort of trapped, and they’re there,” he said. “They can’t escape, and so if you play an audiobook, they kind of have to listen and it’s a way of ensuring they’ll at least give it a try.”

Even with the rise of audiobooks, Willingham doesn’t envision printed books going away anytime soon.

“I think they have different advantages and that’s why I think we’re going to continue to use both of them,” he said.

It turns out that reading is a better method for absorbing complex information or for appreciating the prose of a well-sculpted story. Readers can keep their own pace and circle back with a flit of the eye to revisit material.

“Although one core process of comprehension serves both listening and reading, difficult texts demand additional mental strategies,” Willingham said. “Print makes those strategies easier to use.”

Reading might also have implications for how punctuation is processed and understood, but that hasn’t been researched yet, he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.