In 2002, Vince Biskupic was a Republican candidate for attorney general, the top prosecutor job in Wisconsin, running on his nearly eight years as Outagamie County’s district attorney.

On his now-defunct campaign website, Biskupic listed several people he had successfully prosecuted. Among them: Ken Hudson for the murder of Shanna Van Dyn Hoven; Mark Price and Richard Pease for the murder of Michael Fitzgibbon; James Thompson and Jonathan Liebzeit for the murder of Alex Schaffer; “serial rapist” Joseph Frey; and Kelly Coon for the murder of 2-year-old Amy Breyer.

His Democratic challenger was Peg Lautenschlager, former U.S. attorney for the Western District of Wisconsin. Scot Ross, who was the communications and research director for Lautenschlager’s campaign, recalls that Biskupic ran as a “law and order” candidate.

But shortly before the election, something would happen to undermine that tough-on-crime image.

The Lautenschlager campaign had received a seven-page single-spaced memo from an apparent whistleblower who detailed troubling allegations against Biskupic — including deals that gave “the impression that justice is for sale in Outagamie County.”

The memo included this line: “Far too often, defendants with money are treated differently than defendants who are poor and indigent.”

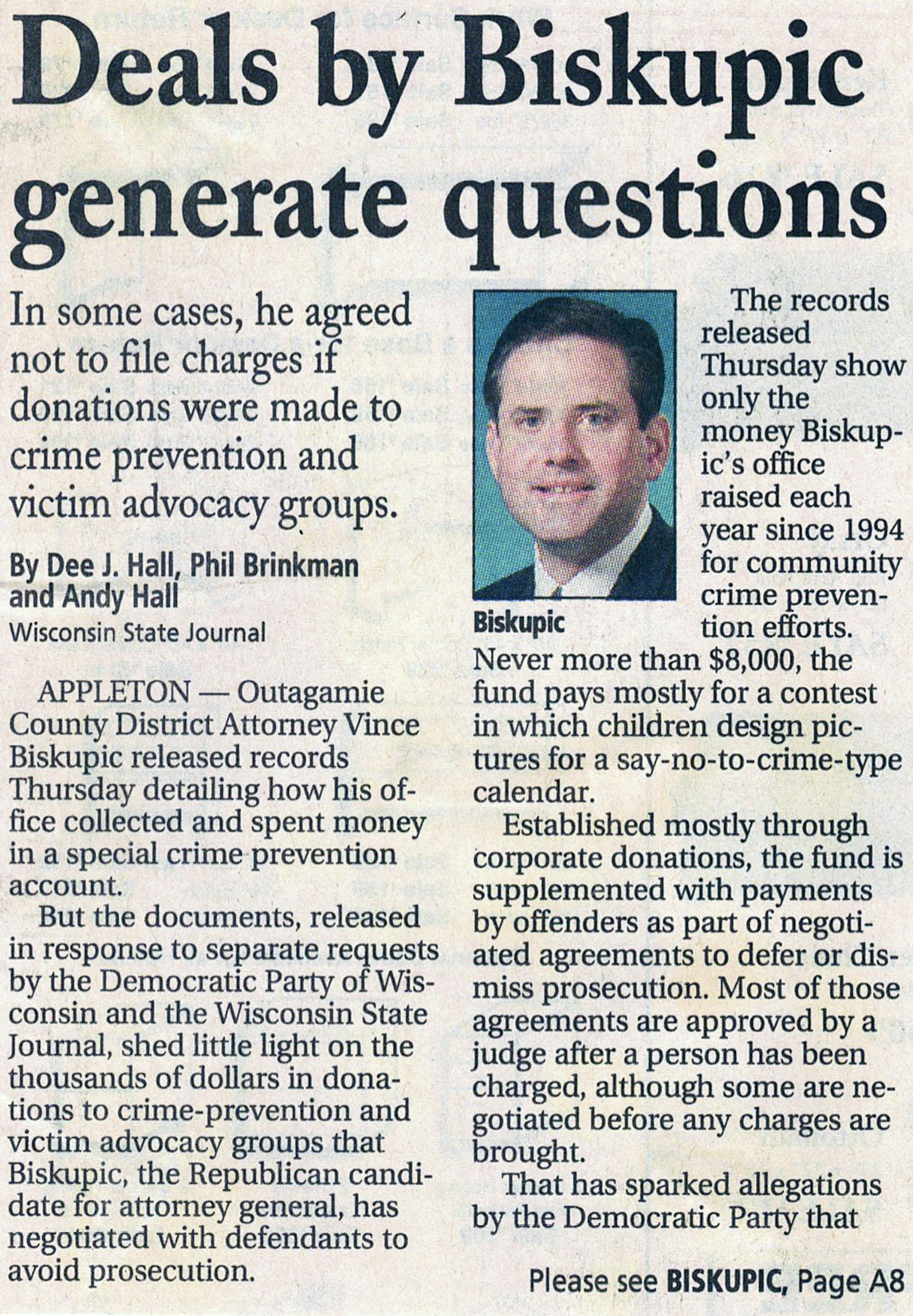

The Democratic Party of Wisconsin filed an open records request with Biskupic’s office seeking records of the alleged deals, which allowed some suspects to avoid charges by paying money. The “donations” went to a “crime prevention fund” in Biskupic’s office or directly to survivors groups and law enforcement associations. Biskupic refused to release the records, so the Democrats sued. And the Wisconsin State Journal filed a similar request for records.

In 1997, five years before Biskupic ran for state attorney general, a panel appointed by the Wisconsin Supreme Court urged judges to reject plea deals that included these kinds of payments. And in 2000, a new law went into effect, making it illegal for prosecutors to dismiss or amend charges in exchange for donations to crime prevention organizations.

But Biskupic’s deals had a twist: : He threatened to charge people but agreed to withhold charges in exchange for “donations.”

The deals also lacked transparency. These “deferred prosecution agreements” looked like official Outagamie County Circuit Court documents, but they were not filed with the court.

Judge: Release the records

The judge who heard the open-records lawsuit filed by the Democrats, Waupaca County Circuit Judge Philip Kirk, was very familiar with such deals, having served on that Supreme Court-appointed panel.

“He (Kirk) started by saying, ‘I don’t know if you know this or not, but I was on a panel that discussed whether or not these crime prevention funds were appropriate or not appropriate — and I think that they are not,’” Ross recounts.

In an interview, Kirk said allowing such deals had the potential to turn into a “goat rodeo.” Allowing people to buy their way out of trouble would create a chaotic and unequal system, he said, an “unmitigated disaster for the state court system.”

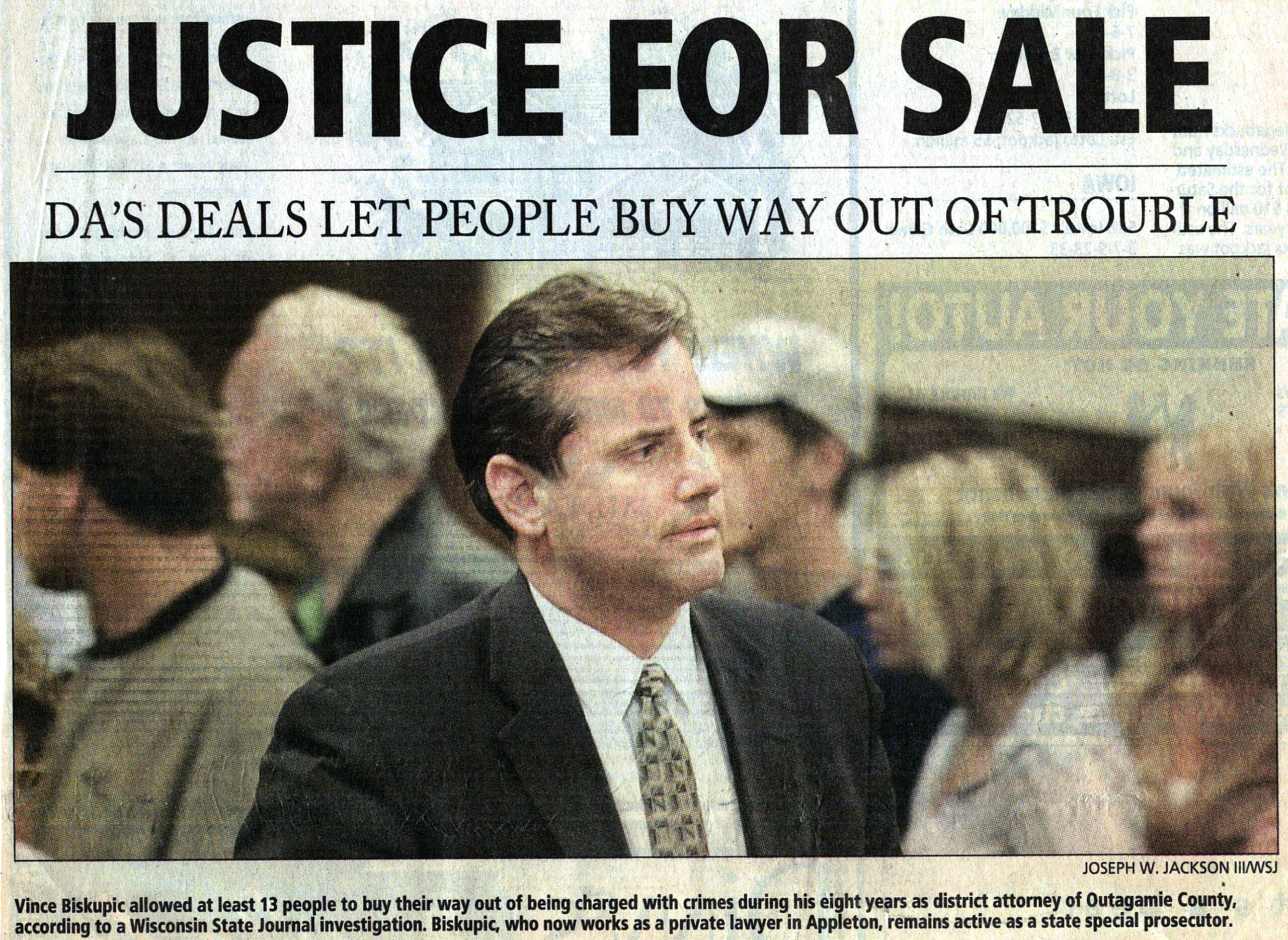

Biskupic agreed to turn over the heavily redacted records to the State Journal, and Kirk ordered him to give the documents to the Democrats as well. The release generated a flurry of negative news coverage including a front page story in the State Journal on Nov. 1 — four days before the 2002 election.

Pace University law professor Bennett Gershman explains why such deals would be so controversial.

“It’s one person who’s wealthy can buy his freedom and somebody who’s poor can’t,” says Gershman, a former New York state prosecutor specializing in official corruption. “It’s just mind-boggling that, that a prosecutor would have something like that, that kind of operation going.”

Whistleblower unveiled

The unnamed whistleblower who wrote the memo exposing the deals was one of Biskupic’s employees, Assistant District Attorney Mike Balskus. In 2002, he wanted to remain anonymous, but he signed a sworn affidavit for the Wisconsin State Journal that his memo was, to his knowledge, true and correct.

“I knew that if Vince Biskupic became the attorney general, that there’d be a lot of problems because I didn’t trust him,” Balskus says. “And I thought he was, I don’t know if you’d say corrupt, because I think he did things for his political gain.”

Balskus was concerned that the legal system — which requires attorneys and judges to report certain types of malfeasance — was not rooting out bad behavior.

“People are silent,” he says. “That’s one of the big problems I see with our criminal justice system.”

Balskus’ memo included at least one deal that Biskupic had not disclosed in his records release — a 2000 agreement with John Mortensen, the president of Jones Sign Co. A car wash had hired Mortensen’s company to make a sign, but after it was installed, the two companies argued over the cost. Mortensen had the sign removed — cutting some wires in the process.

Mortensen said he was puzzled by Biskupic’s threat to prosecute him, as the dispute with the car wash had been resolved two years earlier. And there was another curious aspect to the case: Biskupic’s investigator, Steve Malchow, was a friend of the car wash owner.

Biskupic wanted $10,000 to make criminal charges go away, Mortensen told the Wisconsin State Journal. He agreed to pay $8,000. He told the newspaper he felt “shaken down” by the encounter.

Four days after the records’ release and initial news stories, Lautenschlager won the 2002 election, and Biskupic went into private practice. That next summer, in 2003, the State Journal published a followup series on Biskupic’s deals called Justice for Sale — a line taken from Balskus’ whistleblower memo.

The Wisconsin Ethics Board investigated Biskupic, but found he had not personally profited from the fund. And largely because of that, and because the board only had the power to enforce the state’s Ethics Code, it ultimately did not find that Biskupic violated the law.

But the board condemned the practice, urging “prompt and deliberate action” to close the loophole in the law and sent a letter to district attorneys across Wisconsin, warning them against having crime prevention funds to which people facing potential criminal charges paid money.

Five years after the Justice for Sale stories, then-Sen. Dave Hansen, D-Green Bay, argued in favor of the bill he authored to prohibit such deals.

“This legislation will help restore the integrity of our judicial system by making it clear that justice is not for sale and that people accused of crimes whether they are rich, whether they are poor, or middle class will be treated fairly,” Hansen said in a speech on the Senate floor, never mentioning Biskupic’s name.

The bill passed and was signed into law.

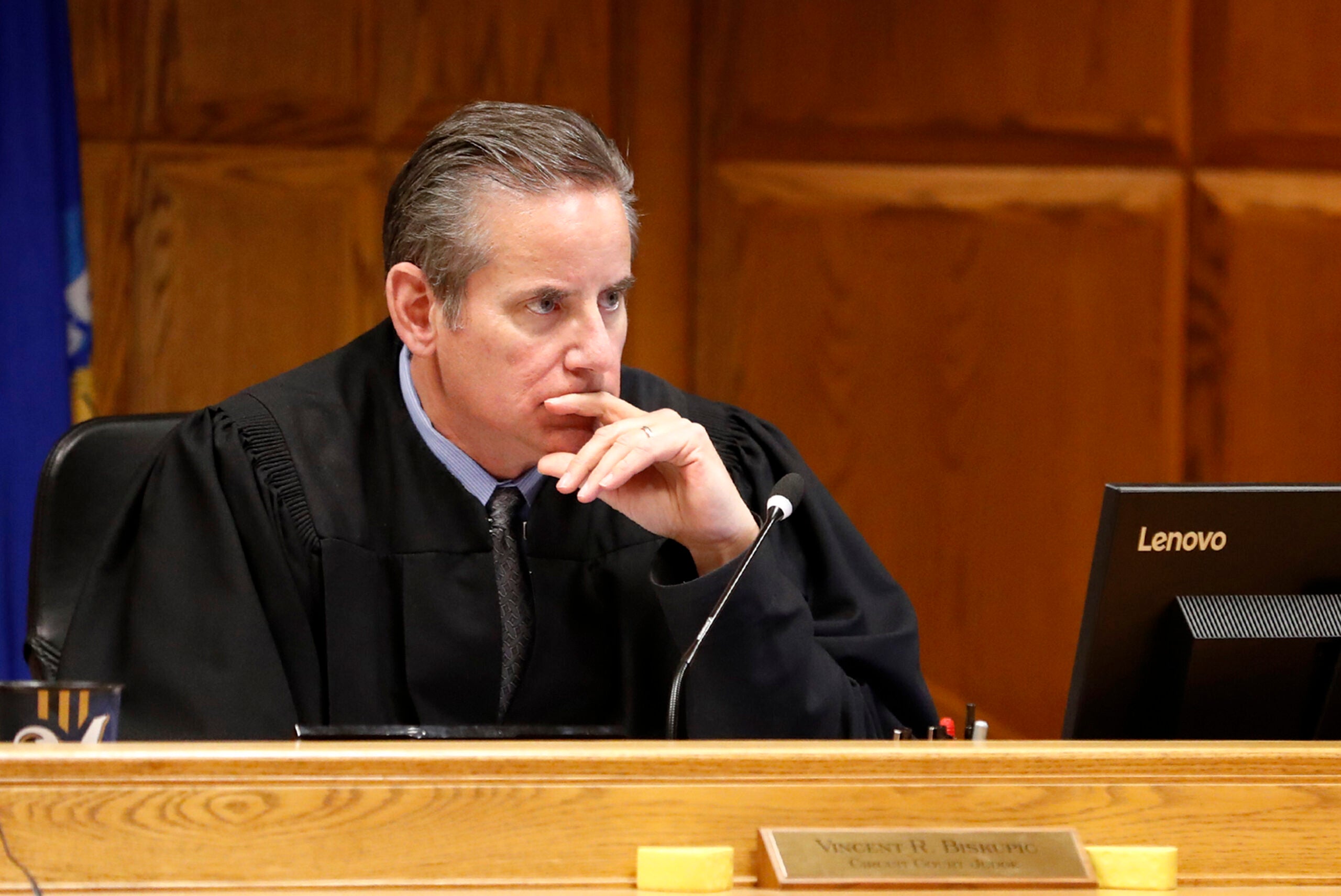

Years later, in 2014, then-Gov. Scott Walker appointed Biskupic — the brother of his campaign attorney, Steve Biskupic — to fill a vacancy on the Outagamie County Circuit Court. A year after that, Biskupic was elected to a full six-year term. He was re-elected in 2021 and remains on the bench.

Biskupic’s ‘gray area’ deals

As a judge, Biskupic also has stretched boundaries, Wisconsin Watch and WPR found. For several years, Biskupic held “review hearings” to monitor defendants’ behavior or to prompt them to pay fines or restitution. The effect was to keep defendants under his control for months or even years after their sentences would have ended.

About two dozen legal experts consulted by Wisconsin Watch and WPR had a wide range of views about Biskupic’s use of review hearings. Some said the practice is legal, some called it a “gray area” and some said it has no basis in state law. Others had never heard of it before.

An analysis of Wisconsin’s electronic court database found 52 cases involving such review hearings; Biskupic was among a very few judges employing this technique — and by far the largest user.

Defense attorneys said they believed Biskupic was trying to help defendants. Former public defender Brandt Swardenski describes it as a way to “chastise them when they screw up and praise them when they do well.”

Some of Swardenski’s clients agreed to undergo review hearings to avoid jail, which Swardenski acknowledges was “a gray area of the law.” He warned defendants who took the deals they might be “subjecting yourselves to further consequences down the line.”

That’s exactly what happened to Beau Jammes.

Jammes had been on probation with the Wisconsin Department of Corrections but was revoked for an alleged violation, which normally would have landed him in jail. Biskupic offered a different path — one with no clear ending.

He let Jammes out of jail and ordered him to get a full-time job, attend counseling or addiction meetings, stay sober, take his medications and work towards a GED. Every few months, Jammes had to return to court to share his progress.

In theory, if Jammes did what Biskupic told him, he might be able to avoid more jail time. At first, Jammes says, he was happy about it. And so was his attorney, Gary Schmidt.

“I thought maybe the judge was just going to run it for a couple of months to make sure that Beau stayed out of trouble for awhile, and then that would end it,” Schmidt recalls, “but he kept extending it and extending it. …There was always something more that the judge wanted.”

Had Jammes just served his jail time at the start, he could’ve been out in about a year. Instead, it turned into a 19-month-long legal purgatory.

Towards the end of this period of uncertainty, Jammes was convicted of disorderly conduct, and the judge in that case sent Jammes to jail. Biskupic then reinstated his original sentence. And although he ordered the sentence to run concurrent with the one Jammes was already serving, it extended the time Jammes spent behind bars.

Biskupic did not answer detailed questions about the practice. Biskupic’s attorney defended the judge’s actions in an email, insisting that earlier court rulings permit them.

In a statement, Biskupic said he considers all sentencing options, and also implied he doesn’t do this anymore. He said the cases mostly were resolved between 2015 and 2018. That’s the same year Jammes filed a federal lawsuit against Biskupic, unsuccessfully challenging his authority to create such a “de facto probation.”

Commenting on that whole practice, Swardenski says, “It was, yeah, I think, pushing the bounds of the statute to say the least.”

Prosecutor’s conduct called ‘alarming’

Gershman, the Pace University law professor, literally wrote the book on prosecutorial misconduct. It’s titled, “Prosecutorial Misconduct.”

“I focus on prosecutors specifically because the prosecutor has the power of life and death,” Gershman says. “The prosecutor has the power to put innocent people in jail for the rest of their lives. The prosecutor has more power than anybody else in America when you think about it. And many, many prosecutors use their prodigious powers responsibly professionally, ethically. Some don’t.”

At the request of Wisconsin Watch and WPR, Gershman reviewed a nine-page summary of issues in seven felony cases prosecuted by Biskupic, most of which were examined in Open and Shut.

“What I saw was alarming,” Gershman says. “What I saw was conduct that was not isolated, inadvertent, marginal — conduct that one could say was simply mistakes in the heat of battle.”

Gershman says Biskupic did the same things over and over again — including withholding evidence.

This is the kind of conduct you might see in 20 prosecutors,” he says. “And I’m looking at one prosecutor. … And the conduct in each of these cases is very, very serious.

As Gershman and other legal scholars have pointed out, prosecutors in this country face very few consequences for their actions. The system has never publicly accused Biskupic — let alone found him responsible — for committing even a single act of misconduct.

And that upsets Gershman.

“It’s a disgrace that the courts and the disciplinary bodies in your state of Wisconsin took no action against this prosecutor, there were no consequences visited upon this prosecutor,” he says.

Gershman was asked why the public should care if a prosecutor does not play fair — especially in cases where the defendant clearly appears to be guilty.

“My guess is that many people in the public won’t care — you know, the end justifies the means, whatever it takes to put these people away, to prevent these people from committing any more crimes is what we want to see,” he says.

“I think,” Gershman says, ‘that’s why it’s so difficult for the criminal justice system to root out bad prosecutors.”

To hear the related podcast, go to Open and Shut (wpr.org/openandshut) or wherever you get your podcasts. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR and other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates. This story is a collaboration between Wisconsin Watch and WPR as part of the NEW News Lab, a consortium of six news outlets covering northeastern Wisconsin.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.