In the spring of 1999, Dale Chu was getting ready to graduate from high school in Appleton, Wisconsin. His parents had lost their home, so he was crashing on friends’ couches.

DALE CHU: And I was homeless. You know, I literally didn’t have an address. I didn’t have a place to call home.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Chu had been in and out of trouble for years: truancy, driving without a license, disorderly conduct. And that spring, he learned that he was going to be a father.

DALE CHU: That’s where, I guess for me, my life really started spiraling out of control.

In October, Chu was picked up for selling cocaine.

DALE CHU: And I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I’m, I mean, I screwed up big time.’ You know, like huge. I mean, I’m facing a felony here.

Whenever he got in trouble, Chu would take the plea deal.

DALE CHU: Why would I ever go to trial and face more time instead of taking the deal? I’m guilty. I did it. You know, I drove without a license. I got caught with this, or got caught with that. I did this; I did that. It’s like, ‘Yeah, give me the lowest amount of sentence you’re going to give me because I was bad.’

But before he got the chance to take a plea on those drug charges, things got worse.

In early December 1999, Chu was working at a gas station. And one day, two cops showed up. They read Chu his rights, and they let him call his boss.

DALE CHU: Hey, I’m getting arrested. They have the doors locked. The pumps off. And they’re letting me stay here until someone comes to relieve me.

The police handcuffed Chu.

DALE CHU: And every time someone pulled up to use the pump, they would push the microphone button, and I’d have to say I’m sorry, you know, we’re not open right now. (chuckle)

The whole thing seemed like a bad joke.

Chu was charged with arson. A judge set his bond at $10,000.

DALE CHU: Are you kidding? This isn’t even, this isn’t even — I didn’t do this.

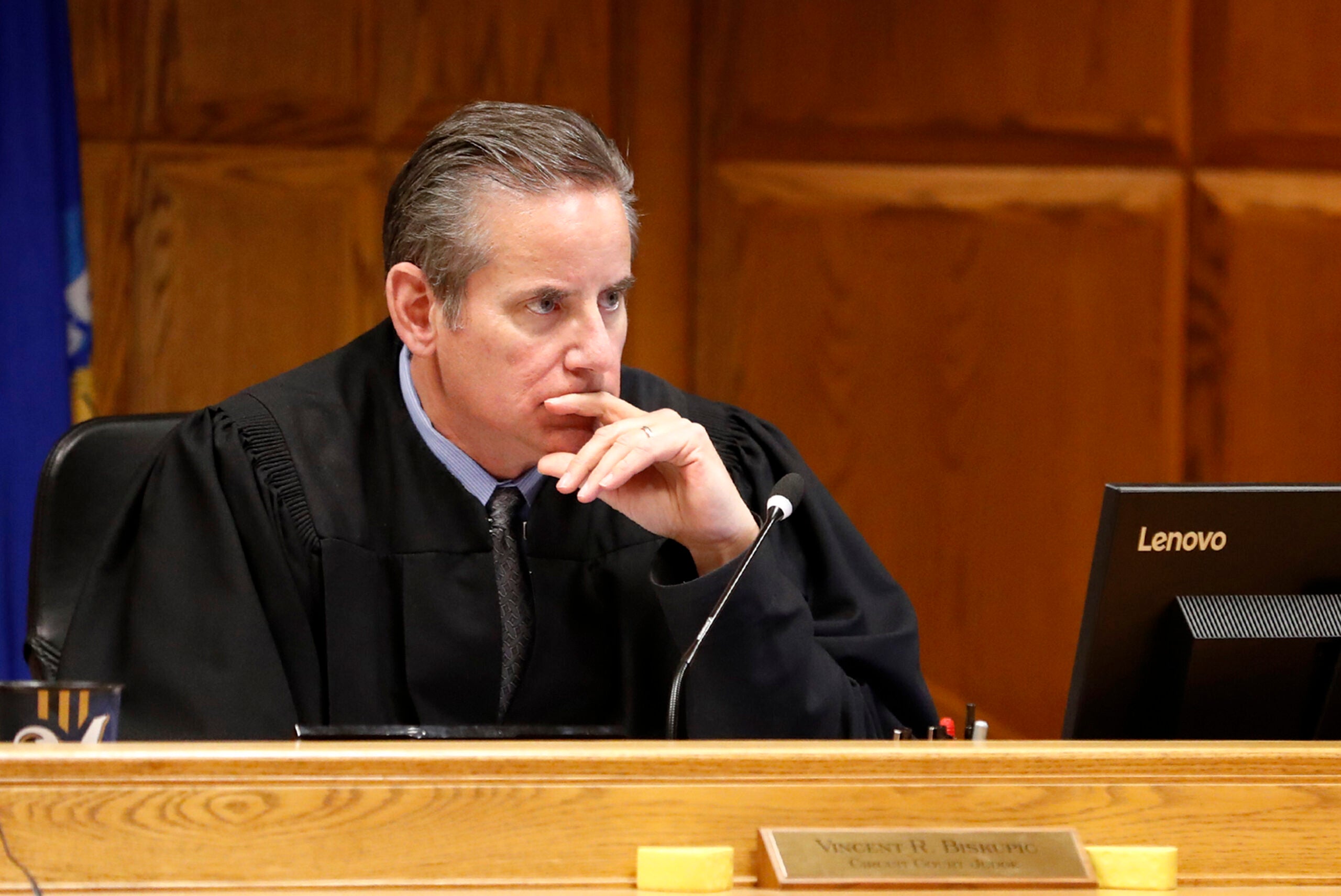

We tend to think that what happens next is in the hands of the jury. But in a lot of ways, it’s in the hands of the prosecutor. In this case, that was Outagamie County district attorney Vince Biskupic.

Comedian John Oliver did a whole segment on the power of the prosecutor for his show, “Last Week Tonight,” in 2018.

JOHN OLIVER: You sort of know deep down how important they are because of a little phrase that crops up constantly in local news crime stories:

REPORTER: Ultimately, it will be prosecutors who decide whether charges will be filed.

REPORTER: Prosecutors will decide whether to file criminal charges.

REPORTER: Prosecutors will decide what happens next.

REPORTER, CHORUS: Prosecutors will decide. Prosecutors will decide. Prosecutors will decide. Prosecutors will decide.

Prosecutors will decide.

The case against Dale Chu wasn’t open and shut. But Biskupic decided he had enough evidence to move forward.

As Chu’s case headed towards trial, he just kept thinking, at any minute, this whole thing would go away.

But that’s not what happened.

CHU: Most people that are adults they’ll know their social security number by heart. I know my department of corrections number and it’s a number I’ll never forget ’cause that’s who I was: Chu 401973.

From Wisconsin Watch and Wisconsin Public Radio, I’m Phoebe Petrovic, and this is Open and Shut.

MIKE BALSKUS: It seemed like a pretty much, open shut case.

KATE O’BRIEN: I mean, this was open and shut.

JERRY BURKE: Nobody would have had to lie. It was an open and shut case.

DALE CHU: Hi Phoebe. This is Dale. How are ya?

PHOEBE PETROVIC: Good. How are you?

DALE CHU: Fantastic, I’m really glad that we got to meet.

Today Dale Chu is in his early 40s.

DALE CHU: I mean, I guess for me it’s always been a hope that I could bring light to this someday and maybe get it off my record.

Chu grew up in Appleton, a city in Northeast Wisconsin.

His parents emigrated from South Korea, and they opened up a dry cleaning business.

Appleton, in the ’90s, was very white. It still is.

DALE CHU: My brother and sister and I were like the only Korean family. Right? So we didn’t really fit in racially. We didn’t fit in with anybody.

By the mid 1990s, the Chus’ business had grown. They had a central store near downtown Appleton with dry cleaning equipment. And they had a handful of satellite locations for drop-off and pickup.

Chu and his two siblings helped out. But he says he wasn’t really close to his parents.

DALE CHU: You know, we didn’t even eat meals together as a family. My dad was always working. I would, I’d see him on Sundays, and I’d see him on the next Sunday. There were weeks that that’s how it went.

Chu and his dad didn’t have heart-to-heart talks or anything like that.

DALE CHU: You know the only thing I remember my dad ever telling me, one time, he was really mad at me (pause) because I had a friend (pause) um…

The friend’s name was Nick Wales. And Chu is hesitating here because Wales would later testify against him in the arson case. We’ll get to that.

But back then, Wales was looking for a job. And Chu helped him get one at the family dry cleaners.

DALE CHU: And all sudden, a pair of Tommy Hilfiger jeans went missing. And everybody swears up and down it’s Nick. And I’m like ‘there’s no way; he would never do that. You know, we’re friends. He wouldn’t steal from my family, make me look bad.’

But one day, Chu was talking to a police officer who told him, no, it was Nick. They had found the pants in his possession.

DALE CHU: And instead of being mad at Nick, I actually said, ‘Oh, well then I took them and I gave them to him.’ And my parents were like, ‘Why would you ever do that for somebody?’ And I remember my dad saying, ‘’ want you to remember something, son. You have black hair, brown eyes — you are different than everybody else.’

Chu’s father had been telling him this since he was little. Black hair. Brown eyes. You’re different. Work harder. Be better.

DALE CHU: It never sunk in. And I never, never cared that I looked different, never cared that my race was different. My friends were my friends because we were friends.

One night, Chu was in his car with two of those friends — both teenage girls.

DALE CHU: We get pulled over. I don’t know why I got pulled over because I didn’t get a ticket. But pretty much the police officer looks and sees me, sees them two girls. And the first question he asks, ‘are you two girls here by your own free will?’ When he first asked the question it didn’t bother me. I thought it was just routine, until the girls started yelling at him.

That’s when Chu realized the question was not routine.

DALE CHU: And I asked him, ‘why am I getting pulled over anyway?’ And he said something about suspicious activity, yada, yada, you know, and just let us go. But, that was my very first ever experience with a racial profiling from a police officer. And I was really mad. And I’m just thinking, wow, what a prick.

On January 4, 1998, the Chus’ main Appleton dry cleaning business was destroyed by fire. This was the fire district attorney Vince Biskupic accused Dale Chu of setting.

Here’s how Chu remembers that day.

Chu and his brother, cousin and some friends had spent the afternoon working at the main dry cleaning store: moving things from one room to another. They later said Chu’s dad was planning to repaint. When they finished, they returned home. But soon after, the boys returned in Chu’s little blue 1986 Chevy Spectrum. Ironically, this part of the story begins with a fire extinguisher.

DALE CHU: For fire prevention, you have to have a fire extinguisher. And one of the fire extinguishers my dad had was expired.

The expired extinguisher was at one of the satellite locations. Chu’s dad had asked him to replace it.

DALE CHU: So that’s what I was supposed to do that day, and I know I forgot to do it, and so here I’m hanging out with my buddies.

Chu and his friends returned to the main location to pick up a new fire extinguisher. They took it from a delivery van. They say they never went inside the building.

But their visit didn’t go unnoticed — thanks to a fancy car stereo Chu had installed.

DALE CHU: So you could hear me coming from five blocks away. Um, it was kind of the thing to do back then.

PHOEBE PETROVIC: Do you remember what music you would have been blasting?

DALE CHU: Yeah, it’d have been ’90s gangster rap.

Chu and his friends later returned to the main store to drop off the expired extinguisher — and saw the brick building surrounded by fire trucks.

He says, at first, he didn’t actually think much about it.

DALE CHU: I wouldn’t have seen that as our livelihood has just suddenly started on fire. That definitely wasn’t a thought (pause). Wow, yeah, I sucked as a person back then (laughs). I was not a good person. You know, even just trying to think about this, man, that’s a huge life event there, and to me it wasn’t and now that I’m reflecting on it, I kind of just brushed it off as, as nothing.

The family had insurance, but the fire was still devastating.

DALE CHU: My parents really couldn’t provide for their family anymore at this point. We had an eviction notice on our house. We had to pack up and get out of there. They lost their business. They lost everything.

His parents moved in with relatives. And this is when Chu started sleeping on friend’s couches, and his life started spiraling out of control.

But the fire was never on his mind — until he was arrested in December 1999 — nearly two years after the business burned.

DALE CHU: And when they had read me my rights and they said, ‘You know, here, we have a warrant for your arrest for the charge of arson, with intent to defraud the insurer.’ And I’m like, ‘Arson for what? Arson for where?’’

Investigators couldn’t track the source of the fire to something accidental — like faulty wiring — so they concluded it was arson.

DALE CHU: You don’t know how it starts then it goes down to arson?

This was a longstanding practice in fire investigations across the country. It’s kind of like saying, ‘We can’t figure out how this guy died. So it must be murder.’

But in 2011, the National Fire Protection Association fully rejected the practice, saying it was quote “not consistent with the scientific method.”

DALE CHU: How do you guys even charge me with this? How does that make any sense at all?

Outagamie County district attorney Vince Biskupic made that decision to charge Dale Chu with arson. Remember, as John Oliver said, “prosecutors will decide.”

But the public doesn’t actually have the right to know why prosecutors make the decisions they make.

A lot of what most of us understand about prosecutors comes from TV programs. Law and Order. Law and Order SVU. Law and Order Trial by Jury.

SOUND EFFECT: Law and Order dum dum

So here’s some basics.

ANGELA J. DAVIS: Prosecutors are the most powerful officials in our criminal justice system.

This is law professor Angela Davis.

ANGELA J. DAVIS: My name is Angela Jordan Davis.

Not to be mistaken with the other Angela Davis, the famous activist. Angela Jordan Davis spent years as a high ranking public defender and now teaches at American University.

Davis says two main powers set prosecutors apart: the power to bring charges and the power to broker plea bargains. These, she says, “control the system.”

ANGELA J. DAVIS: Police officers can only bring individuals to the courthouse door. It is the prosecutor who decides whether that individual will remain in the system, and what they’ll be charged with.

The standard for conviction is proof beyond a reasonable doubt. But the standard for bringing charges is much lower.

ANGELA J. DAVIS: So it allows prosecutors, if they want to, to charge individuals with a lot of offenses that they know they can’t ultimately prove at trial.

This gives them a lot of leverage. A prosecutor might bring multiple charges to ensure some sort of conviction. A person facing five counts and 50 years if convicted at trial might agree to plead guilty to one count and only 10 years.

ANGELA J. DAVIS: But you can see how even an innocent person would take that deal, because going to trial is risky business. You don’t know what a jury might do.

Some scholars call the harsher sentences people face at trial, compared to in plea bargaining, the “trial penalty.”

ANGELA J. DAVIS: And so we have a system of pleas. We have a system in which 95 to 98% of all criminal cases are resolved by way of a guilty plea.

The Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news outlet, said that this means: quote “The only trial those defendants receive takes place in the prosecutor’s office.”

Even just bringing charges — that ultimately get dismissed or acquitted — can upend someone’s life.

And then, of course, prosecutors have the power to decide not to charge. Biskupic could’ve declined to charge Chu. Experts say this power can contribute to class and racial inequities.

Prosecutors do all of this — charging, not charging — with little oversight. Davis agrees with those who describe the prosecutor’s office as a ‘black box.’

ANGELA J. DAVIS: They don’t have to report to a judge or anyone or explain to anyone why they’ve made the choices that they’ve made or tell anyone why they made the choices that they’ve made, or even reveal them, because these are not decisions made in open court. Right? And so that’s an incredible amount of power when you think about it.

45 states, including Wisconsin, elect their top local prosecutors, making the US the only country in the world to do that. And in theory, the ballot box should provide a check.

ANGELA J. DAVIS: But that system doesn’t work that well.

In Wisconsin, these district attorneys run as Democrats or Republicans — and many of us just vote on party lines. That’s one reason why prosecutors go unchecked.

Aside from Dale Chu, the defendants we’re going to talk about in this series are white. That’s partially reflective of the counties we’re looking at. The last census found Outagamie County was about 90% white.

But that’s not reflective of the larger criminal legal system. Across the United States, Black men are incarcerated in state prisons five times more than white men. And Wisconsin actually imprisons Black people at the highest rate of any state.

Racism and racial inequities are endemic to the criminal legal system. And it’s something to keep in mind throughout this series. Everything we’re talking about is, statistically, worse for people of color.

And race definitely came into play in Dale Chu’s case.

When Dale Chu was charged with arson, Vince Biskupic offered him a plea deal. Chu’s lawyer urged him to take it.

DALE CHU: And I’m just like, ah, no, I’m not taking a plea bargain. I didn’t do anything.

And so Chu’s trial began in September 2000.

Arson investigators didn’t agree on exactly how the fire started. So they presented multiple theories to the jury. And Biskupic pointed to Chu’s record, like dealing cocaine.

Neighbors — who probably heard that fancy car stereo — said they saw a man who “generally” fit Chu’s description going into the dry cleaners the night of January 4. And Biskupic presented damning testimony: two witnesses who said Chu confessed to them.

And there was more: Biskupic said that the dry cleaning business was in financial trouble. Just days before the fire, Dale Chu’s dad, So Man Chu, had taken out an additional $80,000 insurance policy. A police officer testified that So Man Chu had submitted an insurance claim of almost half a million dollars — but that the burned inventory in the store wasn’t worth nearly that much.

Biskupic also told the jury that because of Chu’s quote “Korean culture, he was very devoted and loyal to his father.” And he said Chu committed arson quote “because his father put him up to it.”

DALE CHU: Because he’s Korean, he has to do what his dad tells him to do. I’m like, there’s no way they’re going to buy that.

(pause)

DALE CHU: Never once, either — even when the jury was out for deliberation, I never thought they were going to come back with a guilty verdict.

But the jury did find him guilty. Chu was ordered to pay over 100,000 dollars in restitution to the insurance company. And he was going to prison… at 19 years old.

DALE CHU: I guess I don’t understand to this day how I’d lost that trial. The only thing I can think of is Vince portrayed me as a bad enough person that it didn’t matter if I was guilty or not. Best thing for our community and our society, in Appleton, Wisconsin, is that this guy’s off the streets. And he wouldn’t have been wrong.

Chu’s father was later charged with defrauding the insurance company. He pleaded no contest, which meant he didn’t admit or deny guilt, but he accepted that prosecutors had enough evidence to convict him.

PHOEBE PETROVIC: Just to be clear, ’cause I need to sort of ask you outright. Were you ever asked by your father to, you know, set the business ablaze in order to help with some sort of insurance scheme?

DALE CHU: Absolutely not. If they could only see how hard a time my parents had after losing the business. If they wanted to do it, they should have done it at a satellite store. Get rid of one of the little stores, then you don’t have to worry about it (laughs). But you can’t operate. The main store goes down. It’s the only one that has all the equipment to do the work. If that goes down, all your stores went down. It wouldn’t have even been worth it.

I told you that the case against Chu wasn’t open and shut. And I’ve already mentioned one of the flaws – investigators couldn’t find a specific cause for the fire, so they concluded it was arson.

But what about those two witnesses who said that Chu had confessed to them?

One of them was Nick Wales.

You remember Nick. He’s the one who was working at the dry cleaning business when Chu says that pair of Tommy Hilfiger jeans went missing. Chu and Wales had a falling out months later.

At trial, Wales testified that Chu confessed to him that he’d started the fire.

But here’s what the jury didn’t hear. Before trial, Wales changed his story multiple times.

First he signed an affidavit alleging that an investigator in Biskupic’s office offered to help “get rid” of some pending criminal charges if Wales would tell police what he knew about the fire. So Wales said that Chu confessed.

Later, that same investigator helped Wales even further — quashing a warrant for his arrest.

Wales claimed in his affidavit that the investigator told him to keep this all a secret, because it would quote “look bad for the case.” He also said the investigator told him to lie on the stand if questioned about any promised favors.

Back in 2005, my boss Dee Hall wrote a story about Dale Chu’s case. And she got in touch with the investigator. His name is Steve Malchow. Remember that name, because it’s going to come up again in this series.

Malchow told Dee he never asked Wales to lie about what he knew — but he did suggest that Wales not tell his attorney about the help he had received.

Before the case went to trial, Wales changed his story twice more.

The jury never heard that Malchow offered to help Wales with his pending criminal cases in exchange for his testimony.

And the judge didn’t allow the contradictory statements into evidence. Jurors in Chu’s case never heard the full Nick Wales saga. They just heard Biskupic call Wales a quote “credible witness.”

Ten days after Biskupic told the jury that Wales was credible, his office prosecuted Wales for lying in that original affidavit.

Before he was sentenced, Dale Chu says he ran into Nick Wales at the Outagamie County Jail.

DALE CHU: Nick was in the cell block next to me, and I had seen him. And I talked to him through the door. I’m just like, ‘You realize that you just sent me to prison for a long time.’ I said, ‘Why would you do something like that?’ He’s like, ‘Well, they gave me a deal.’ I said, ‘Well you said that, in trial — why don’t you say anything?’ ‘Well, I don’t want them to take the deal back.’

I tried to get in touch with Nick Wales, but I couldn’t reach a working phone or email. And the letters I sent to two addresses got kicked back.

I should mention that a second witness — a woman close to Chu — told jurors he confessed to her, too. But two other witnesses said that this woman was also facing legal trouble. And that police had threatened to put her in jail if she didn’t quote “bring something up against” Chu. I have not been able to verify this claim.

Over a year after his conviction, Dale Chu brought his case to the Wisconsin Court of Appeals, arguing, among other things, that Biskupic withheld evidence about the credibility of the two witnesses who claimed Chu confessed — and that the cause of the fire was never determined. The court ruled against him. So Chu’s sentence of seven years in prison stood.

Chu got out of prison in 2004. He’s since gotten married and had more kids. He was part owner of a popular restaurant in Appleton for a while. In the last year, he moved to Virginia and opened a food truck.

He says he’s really turned his life around.

But even though Chu has moved on, there’s one aspect of the case that still really bothers him.

DALE CHU: You could bring up my case to convict someone based on their ethnicity.

Remember, Biskupic told the jury that Chu’s Korean background was evidence of motive. He committed arson because his dad told him to, and Korean sons listen to their fathers.

The Court of Appeals said that was allowed. Saying, quote “although there is no place in a criminal prosecution for ‘gratuitous references to race,’ the State may properly refer to race when it is relevant to the defendant’s motive.”

And this became legal precedent in Wisconsin.

It’s even cited in a footnote in a document lawyers use when interpreting the state constitution.

ABBE SMITH: Well that’s a really interesting case, the whole context of it. Um I’m sorry I got a barking dog. Can I hang on for one second, put him away?

This is Abbe Smith.

PHOEBE PETROVIC Can I ask what your dog’s name is?

ABBE SMITH: (Laughs) He’s a two-year-old Welsh Terrier named Habeas. That’s what happens when you’re a criminal defense lawyer: you name your dog Habeas.

Smith is a law professor at Georgetown University, where she’s been a long-time advocate for the rights of defendants.

Defendants like Dale Chu.

ABBE SMITH: So what was the basis of those statements? Was there anybody who testified that in Korean-American culture, you know, there’s a powerful dynamic between father and son so that the fathers can get the sons to do almost anything?

The only person who testified to something like this was that second witness who told jurors Chu confessed. A white woman he sometimes called “Mom.” She told the jury how Chu had described Korean culture: quote – “To my understanding, if his father asked him to do something, he would do it.”

ABBE SMITH: That evidence seems like the phoniest sort of dog-whistle, you know, race-based evidence that I’ve ever heard of. It’s offensive. It just kind of plays on ethnic stereotypes.

To a layperson, racial stereotyping, disagreement on how exactly the fire started, relying on a witness who was later charged with perjury — it feels wrong. Prosecutors are supposed to seek justice — not only convictions.

ABBE SMITH: Too often prosecutors have a kind of occupational hazard, you know, see a crime, a provable crime, let’s bring charges.

Smith says this win at all costs approach to justice has created a huge problem.

ABBE SMITH: I hold prosecutors chiefly responsible for mass incarceration in this country.

Over two million people are behind bars in the US. Ours is the highest incarceration rate in the world.

ABBE SMITH: Whenever I say it, I feel like there ought to be a moment of silence. It’s an astonishing number of people to be in cages in the United States of America in the 21st century. Just astonishing.

Smith argues that prosecutors need to change their approach to lower-level charges, in particular.

ABBE SMITH: A disproportionate number of those who get caught up in repeat misdemeanor conduct have mental health problems, substance abuse problems, alcohol problems, they’re homeless. I mean, is it necessary to throw the book at people? That’s a permanent record. That’s a permanent mar.

About 80% of criminal convictions in the United States are misdemeanors.

The public is starting to pay more attention to mass incarceration and its effects on society.

But Smith says prosecutors are still quick to bring charges.

ABBE SMITH: My students are endlessly calling up prosecutors, emailing prosecutors, trying to get them to either drop a case or place a client in a diversionary program. And I can’t tell you how often the prosecutor’s rejoinder is, ‘Well, we can prove it. This is an easy case to prove.’ But that is not supposed to be the overriding question for charging a criminal offense. You know? Yeah. Sometimes you can, you can prove it. But do we want to? You know, isn’t there a, you know, a more graceful intervention that might actually make a longer term difference?

In the summer of 2019, I was hired to investigate one case Vince Biskupic prosecuted. A case where — it was alleged — a vast conspiracy involving prosecutors, investigators and multiple police agencies had framed a man for a murder he did not commit.

And I’m just going to tell you right now, that’s not what I found.

But I did find questionable behavior in that case. And that questionable behavior led me to other cases Biskupic prosecuted — and to questions about how prosecutors around the country use their power in unexpected — and sometimes troubling ways.

I want to be clear about something. I’ve tried multiple ways to reach Vince Biskupic and to ask him for comment on all of the cases we’re going to talk about in this series. We even sent him detailed questions via registered mail. He has never responded.

Prosecutors often make the news when they’ve committed some kind of headline-grabbing misconduct. Here’s some examples. Since 2010, prosecutors have been caught raiding a defendant’s cell and stealing legal documents protected by attorney-client privilege, sexting a sexual assault victim — and offering bonuses to prosecutors who hit conviction quotas.

But most of the behavior we’re going to talk about in this series isn’t that salacious. Instead, it’s the kind of thing that could happen in any criminal case. Things like withholding evidence or using questionable testimony.

I asked Abbe Smith why we, the public, should care about this type of behavior. Some people might consider it “workaday.”

ABBE SMITH: Isn’t it terrible that you can call it workaday misconduct? I don’t think there is such a thing as workaday misconduct. There are professional responsibilities, but there are also moral responsibilities when you’re talking about loss of liberty.

In our next episode, we’re going to talk about what it takes for a prosecutor to get into serious trouble: flashy, textbook bad behavior. Because it does happen.

For that, we have to look no further than one county south of Outagamie, where a controversial district attorney made his mark in the 1990s.

It wasn’t Vince Biskupic. It was Biskupic’s former boss, a prosecutor named Joe Paulus.

JERRY BURKE: If you said anything bad against Joe, what the hell is wrong with you? You’re an idiot.

EJ JELINSKI: The majority of the time he spent playing with people just for his own amusement. And he was cruel. He was quite cruel.

MIKE BALSKUS: Vince would follow Joe around like a puppy dog. Joe was his mentor.

To hear the related podcast, go to Open and Shut (wpr.org/openandshut) or wherever you get your podcasts. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR and other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates. This story is a collaboration between Wisconsin Watch and WPR as part of the NEW News Lab, a consortium of six news outlets covering northeastern Wisconsin.