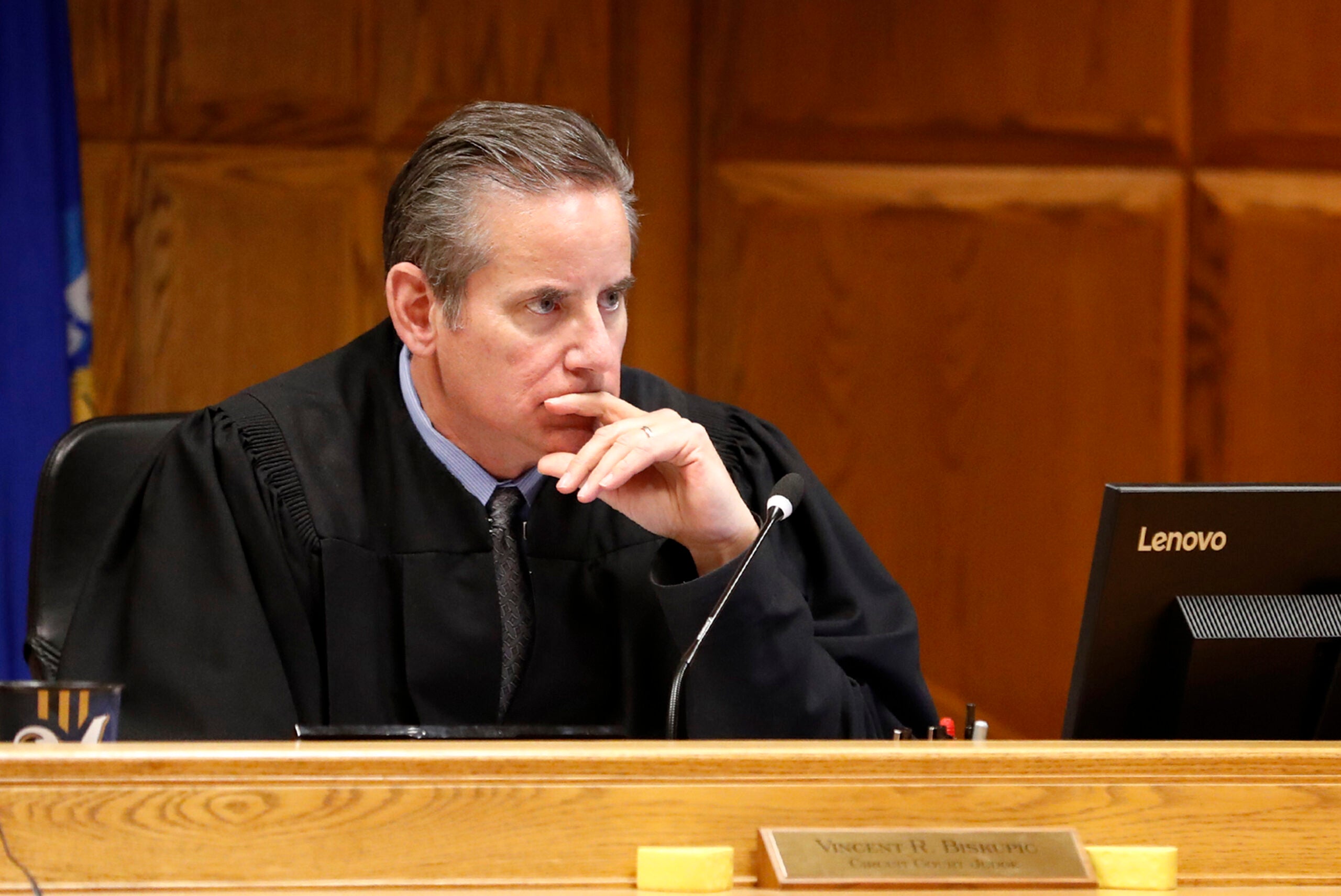

In 2002, Vince Biskupic had been the District Attorney in Outagamie County for about eight years. And he decided to set his sights higher. He started running for the top prosecutor job in Wisconsin: Attorney General.

A year earlier, he’d put away Ken Hudson for life for the murder of Shanna Van Dyn Hoven. And Biskupic’s campaign website touted his high profile convictions.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

PHOEBE PETROVIC: ‘Serial killer David Spanbauer. Killers Mark Price and Richard Pease. Child killer Kelly Coon. Killers James Thompson and Jonathan Liebzeit. And then serial rapist Joseph Frey.’

His campaign ads also talked about his convictions. Like this one, with Van Dyn Hoven’s mom.

VAN DYN HOVEN’S MOTHER: He had a tremendous amount of compassion for us. His prosecution was flawless.

RADIO AD VOICE OVER: Vince Biskupic, a prosecutor, not a politician, for Wisconsin Attorney General.

VAN DYN HOVEN’S MOTHER: Vince Biskupic wants to leave the world a better place than he found it.

His Democratic challenger was a former US attorney named Peg Lautenschlager.

SCOT ROSS: There was a definite distinction between the two of them.

Scot Ross served as the communications and research director for Lautenschlager’s campaign.

SCOT ROSS: Her opponent, you know, did the Republican line of, ‘We’re just going to throw everybody in prison, basically. You know, everybody’s a crook. We’re gonna throw them all in prison.’ He was the law and order candidate.

But on the eve of the election something would happen that would undermine that tough-on-crime image.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: That is one of the most outrageous things I think we can think of for a prosecutor to do. Uh, really, when I think about that, it’s, it’s just absolutely abhorrent.

From Wisconsin Watch and Wisconsin Public Radio, I’m Phoebe Petrovic. And this is the final episode of Open and Shut.

MIKE BALSKUS: It seemed like a pretty much, open shut case.

KATE O’BRIEN: I mean, this was open and shut.

JERRY BURKE: Nobody would have had to lie. It was an open and shut case.

Just a few months shy of the election, the Lautenschlager campaign received a tip detailing troubling behavior by Outagamie County District Attorney Vince Biskupic.

The Democratic Party of Wisconsin filed an open records request with Biskupic’s office. Here’s Scot Ross again.

SCOT ROSS: It went very quickly. Okay, here’s some information this might be going on. This is a government official. Let’s get the records and see if this is true or not.

Biskupic denied the request.

And so, the Democratic Party of Wisconsin took him to court.

At the time, my boss, Dee Hall, was a reporter at the Wisconsin State Journal. And she noticed the Democrats were suing to get records from Biskupic.

DEE HALL: And it occurred to me that a lot of stuff happens before an election, but rarely do the parties or the campaigns actually spend real money on an attorney to raise issues. And so I figured there’s something here.

So Dee says she got in touch with Scot Ross.

DEE HALL: Asked him, ‘What do you guys have?’ And that’s how it started.

Dee says she met Ross in person and got her hands on a memo — a memo that appeared to be written by a whistleblower working inside Biskupic’s office.

DEE HALL: A very lengthy, single-spaced document that laid out dozens and dozens of allegations.

There were a lot of allegations in the memo. Some were small. Some we’ve talked about elsewhere in this series. And others have yet to be confirmed.

But the section that led the Democratic Party of Wisconsin to file that lawsuit included this line: quote “Far too often, defendants with money are treated differently than defendants who are poor and indigent.”

In a nutshell, the memo alleged that Biskupic was offering deals — allowing some suspects to avoid legal trouble by paying money.

And this wasn’t restitution — money that goes to the victim of a crime. Some of the money went into a crime prevention fund, controlled by Vince Biskupic.

DEE HALL: But the notion was that this was really only offered or able to be taken advantage of by people who had money.

With money from his fund, Biskupic published a say-no-to-crime type calendar featuring artwork from local children. And he sometimes required suspects to pay money directly to survivors groups and law enforcement associations.

And while Biskupic wasn’t pocketing the money — like his former boss Joe Paulus had — he could have benefited indirectly from these funds.

DEE HALL: There isn’t a race in Wisconsin where a DA or an Attorney General doesn’t trot out some law enforcement person to swear that they’re, you know, tough on crime. So, you know, it, it just allowed him to maintain these positive relationships with victim groups, with the police, um, and then ultimately the community, too.

At first glance, this didn’t seem all that different from something other district attorneys in Wisconsin had done in the past.

In 1997, five years before Vince Biskupic ran for state attorney general, a panel appointed by the Wisconsin Supreme Court urged judges to reject plea deals that included these kinds of payments. And in 2000, a new law went into effect, making it illegal for prosecutors to dismiss or amend charges in exchange for donations to crime prevention organizations.

For reasons we’ll get into later, almost all of the deals Biskupic was being accused of making didn’t break this law. But that was only part of the issue.

There was also the lack of transparency.

DEE HALL: These were secret deals.

These cases were often being resolved in a way that bypassed judicial oversight. And according to the memo, Biskupic had denied open records requests about the fund.

The whistleblower warned that the payments gave quote “the impression that justice is for sale

in Outagamie County.”

Just days before the election, the Democratic Party of Wisconsin appeared in Outagamie County Circuit Court to challenge Biskupic’s denial of their open records request.

Scot Ross was in the courtroom that day, and this is what he remembers the judge telling Biskupic’s attorney.

SCOT ROSS: He started by saying, ‘I don’t know if you know this or not, but I was on a panel that discussed whether or not these crime prevention funds were appropriate or not appropriate, and I think that they are not.’

I actually interviewed that judge about this. He described the worry to me in two words: goat rodeo.

He went on to explain that the panel of judges felt that without some regulations, those crime prevention funds would lead to inequality that would create a quote “unmitigated disaster for the state court system.”

By the time of the hearing, Dee’s employer, the Wisconsin State Journal, had filed its own request for the records. And Biskupic’s lawyer told the court that the district attorney’s office would comply with that request. And so, the judge said, Biskupic needed to hand over the records to the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, as well.

SCOT ROSS: And basically the judge then said, ‘You’re going to turn over these records and you’re going to turn them over now.’

Dee and her colleagues at the Wisconsin State Journal were now on the clock. Remember, the election was just days away — and they had a lot of work to do.

DEE HALL: So we get records of the deals. They’re heavily redacted and a lot of times we can’t even tell who are the deals with or even sometimes what the allegations were that might’ve led the DA to threaten to charge them with something.

The reporters realized that in order to really cover this story, they needed to solve another mystery: the name of the whistleblower who wrote that seven-page memo.

DEE HALL: We found out that it was assistant district attorney Mike Balskus.

Mike Balskus. You remember that name. We’ve already told you a bit about him. He’s the prosecutor who, starting in 2003, would investigate misconduct allegations against former Winnebago county district attorney Joe Paulus.

At the time of the 2002 election, Balskus was an assistant district attorney in Outagamie County. He’d been there since before Biskupic got elected. He remained there throughout Biskupic’s tenure — and worked for him for eight years.

MIKE BALSKUS: I knew that if Vince Biskupic became the Attorney General, that there’d be a lot of problems because I didn’t trust him. And I thought he was — I don’t know if you’d say corrupt, because I think he did things for his political gain.

I first met Mike Balskus in 2019, almost two decades after he wrote that memo. And even after all those years, he still had boxes and boxes of documentation he collected on his former boss.

MIKE BALSKUS: Part of the problem when you’re doing something like this is it’s very easy for somebody to say, ‘Oh, you’ve got a bias against this person.’ So that’s why you have to document it.

And, just to put this all in context: while Vince Biskupic was running for state attorney general, Joe Paulus was running for reelection in Winnebago County. And all those rumors were swirling around about drunk driving cases that seemed “hinky.”

The accusations Balskus was making against his boss weren’t the same thing as what Paulus had done. But Balskus was still concerned.

MIKE BALSKUS: I would look at files. I would, all of a sudden it was like, ‘Oh, Hmm. Why is, you know, why is this happening? Why is that happening? Huh?’

With his boss running for state attorney general, he realized it was time for him to speak up.

MIKE BALSKUS: People are silent. That’s one of the big problems I see with our criminal justice system.

When Dee contacted Balskus in 2002, he wanted to remain anonymous. After all…

DEE HALL: Biskupic could have fired him at any moment, and so he was taking a great risk with his career. And at that moment we agreed to keep his name out of the stories.

At Dee’s request, Balskus signed a sworn affidavit that the information in his memo was, to his knowledge, true and correct.

DEE HALL: We used that as a basis to find out about some of the other deals that were not released as part of the records release. It made us know that, in fact, there were other deals out there that Biskupic still had not turned over.

Dee and two other reporters — including her husband and co-worker Andy Hall — got to work. Reporting on deals Biskupic had disclosed, and others that he still had not disclosed — despite the judge’s order to turn over all the records.

The day after the hearing, the Wisconsin State Journal had a story on the front page. The date: November 1 — four days before the election.

Dee’s story didn’t accuse Biskupic of doing something illegal. But she wanted to know: was Biskupic doing something unethical?

In her article, Dee told the story of John Mortensen, the president of a sign company — which is now the official sign company of the Green Bay Packers.

A car wash hired Mortensen to make a sign. But after it was installed, the two companies argued over the cost of the work. And Mortensen had the sign removed — cutting some wires in the process. He said the dispute with the car wash was resolved in 1998.

But, two years later…

DEE HALL: He was called into the District Attorney’s office and told that he would be charged with criminal damage to property and with grand theft, both of which are felonies, or he could donate some money to the DA’s office.

We don’t know why this was brought up two years after the dispute, but there’s something Dee uncovered that could have been a factor.

DEE HALL: The owner of the car wash was actually a friend of the investigator in the District Attorney’s office.

That investigator was Steve Malchow. His name has come up again and again in this series.

Biskupic reportedly told Mortensen that he could avoid criminal charges if he paid $10,000 to the crime prevention fund. And Mortensen…

DEE HALL: He ended up having to pay $8,000 to get out of basically trouble with the law. He told us he felt, quote unquote, shaken down by the encounter.

Dee interviewed Biskupic back then and he said, he probably hashed out these kinds of deals fewer than 10 times a year. Sometimes it was just an efficient way to resolve a case.

And again, Dee says having defendants pay a fine is not unheard of.

DEE HALL: Sometimes really the, the best resolution is somebody pays a couple of hundred bucks and then it, they just move on with their life. You know, somebody spray paints graffiti at a, at a cemetery, and they go clean it up and you make them pay $200. The difference with these is it wasn’t a couple hundred bucks. It was thousands of dollars in some cases.

Biskupic insisted he hadn’t done anything wrong. And he made a really fine distinction. Remember: that 2000 law had made it illegal for prosecutors to dismiss or amend charges in exchange for donations. Biskupic told Dee he hadn’t done that.

DEE HALL: Mr. Biskupic explained that he never charged these people. He just threatened to charge them.

By accepting payments from people who had not been charged with a crime, Biskupic had exploited a loophole in the law.

We’ve already talked about how a prosecutor’s discretion to negotiate plea bargains is really powerful. And we often don’t know how prosecutors make their decisions because those decisions happen behind closed doors.

But because of Mike Balskus’s whistleblower memo, we got a glimpse into the black box. And what we learned is that one way Vince Biskupic made deals was by allowing people to buy their way out of trouble.

During his campaign, Biskupic had emphasized he was a prosecutor, not a politician.

SCOT ROSS: It was an absolute contradiction, and, you know. It was like, ‘What, what is going on up there?’

That’s Scot Ross again.

SCOT ROSS: Why is he allowed to do this? What kind of, you know, Boss Hogg, Roscoe P, Coltrane operation is he allowing to have happen up there?

Just in case, like me, you’ve never watched the 80s TV show The Dukes of Hazzard, Ross is talking about the comically corrupt county commissioner Boss Hogg and his sidekick sheriff Roscoe P. Coltrane.

DUKES OF HAZZARD: If Sheriff Roscoe runs the county, Boss Hogg runs Roscoe.

SCOT ROSS: That was a way in which we used to characterize what was going on. And it needed, and it was something that needed to be exposed — not just because in the context of the Attorney General’s race, but it needed to be exposed because what was going on was wrong.

Four days after Dee’s story went out, Wisconsinites went to the polls.

DEE HALL: We can’t know whether it affected the race. There was no pre-election or post-election, uh, polling, but it was a very, very close race and the Democrat did win: Peggy Lautenschlager.

Biskupic had given up his seat as Outagamie County District Attorney to run for Attorney General. So after he lost the election, he went into private practice.

Dee and her reporting team at the Wisconsin State Journal kept digging into Biskupic’s crime prevention fund.

That next summer, they released a series called “Justice for Sale” — a line taken from Balskus’s whistleblower memo.

Dee and Andy Hall interviewed leaders of the Republican Party in Outagamie County, and they stood by Biskupic. One said that he wasn’t convinced there was a quote “ethical smudge.” Another said that people in Appleton quote “think the world of him and his family.”

Following Dee’s reporting, the Wisconsin Ethics Board investigated Biskupic.

The Board found that Biskupic had not personally profited from the fund. And largely because of that — and because the Board only had the power to enforce the State’s Ethics Code — they ultimately did not find that Biskupic violated the law.

So they didn’t issue a penalty, and decided not to take any further action. But the Board went out of its way to comment on something that wasn’t covered by the Ethics Code: the way that Biskupic was offering not to charge people with crimes if they paid up. The Board condemned the practice, and it urged quote “prompt and deliberate action” to change the loophole in the law.

And the Board sent a letter to all of the district attorneys in the state of Wisconsin reiterating that they should not control a crime prevention fund to which, quote, “potential criminal defendants pay money.”

DEE HALL: Mr. Biskupic, of course, painted this as an exoneration.

In a press release, Biskupic said, quote, “Salacious headlines can’t alter the truth. The facts are that these programs are essential and a legitimate part of the law enforcement process.” End quote.

The press release suggested Biskupic had been cleared. Dee reached out to the executive director of the Ethics Board who told her that characterization was inaccurate.

But the Ethics Board’s investigation doesn’t seem to have made a big impression on the people of the Fox Valley.

Remember former TV reporter Jerry Burke? The one who says he always thought a lot of Biskupic?

We asked him about all this when we visited his home in 2020.

DEE HALL: Do you recall that there was a scandal?

JERRY BURKE: Oh, you’re going to have to refresh my brain on this one.

To be fair, Burke was busy following a much bigger story at the time: the federal investigation into Joe Paulus for taking bribes.

So we explained it all to him: The secret deals. Justice for Sale.

JERRY BURKE: I never knew this. This is news to me. Honest to God.

DEE HALL: Yeah.

JERRY BURKE: Um, this I’m — this is the first I’ve ever heard of this. Interesting.

We’ll be right back, after a quick break.

—

Hey Open and Shut listeners. Investigative journalism like this costs time and money. Getting these stories right takes research over weeks, months and — in this case — years. That’s where you come in. Your support of in-depth and independent journalism makes everything we do possible. Support fact-checked journalism that has a direct impact on people’s lives by making a donation to Wisconsin Watch and Wisconsin Public Radio.

Learn more and donate to Wisconsin Watch and WPR at wisconsin watch dot org and WPR dot org. Thank you.

—

In the wake of the justice for sale stories, Wisconsin lawmakers tried — and failed — multiple times to close the loophole.

In January 2008, they tried again.

ARCHIVAL: Senate bill 244. Prosecution decisions…

Senate bill 244.

ARCHIVAL: Senator from the 30th is recognized.

ARCHIVAL: I wanted to speak to this…

The senator was Democrat Dave Hansen. His district included most of Green Bay. And if you didn’t have the legislative map memorized, his Green Bay Packers tie offered a clue.

ARCHIVAL: This legislation will help restore the integrity of our judicial system by making it clear that justice is not for sale and that people accused of crimes, whether they are rich, whether they are poor, or middle class, will be treated fairly. Thank you, Mr. President.

The bill passed and was signed into law. But even though lawmakers cited Dee’s reporting during the debate, Biskupic’s name did not come up. Not once.

When lawmakers closed the justice for sale loophole, Biskupic had been in private practice for about five years. And he’d remain largely outside of the public eye for a few more.

That is, until August of 2014 — when an Outagamie County judge retired and left a vacancy.

It had been over a decade since Dee and her colleagues exposed the Justice for Sale controversy.

By this time, Republican Scott Walker was the Governor of Wisconsin — with the power to appoint judges when there was a sudden vacancy. Biskupic’s brother, former US attorney Steven Biskupic, was serving as Walker’s campaign attorney.

In September, Vince Biskupic was appointed to the bench.

SCOT ROSS: I literally ran to the press office like, ‘Are you kidding me?’

That’s Scot Ross again. Back then, he was working at a liberal advocacy group.

SCOT ROSS: And I looked around the room and nobody in the press room had been there when this all happened in 2002, and I said, ‘Ahh, darn it.’

A year later, Judge Vince Biskupic was elected to a full six-year term. He was re-elected in 2021.

Bennett Gershman, a law professor at Pace University, isn’t surprised that someone with Biskupic’s history became a judge.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: It’s certainly endemic all over the country that prosecutors — even bad prosecutors — become judges. And I’m not going to comment on how they do their judging, but it may be that their judging is similar to their prosecuting.

As I neared the end of reporting this series, I found myself wondering, how — as Gershman put it — Biskupic did his judging.

So I contacted a bunch of defense attorneys who’d appeared before Biskupic. And of those that responded, a bunch said that he was thoughtful.

But a couple attorneys mentioned something else. And it was really interesting.

They said, ‘Well, he does this one thing, where instead of sending people to jail, he makes them come back for multiple hearings. And, it’s pretty weird, and I’m not sure if it’s legal.’

One of the people I talked to was former public defender Brandt Swardenski.

And he told me, he believes Biskupic had good intentions when he did this. Several other lawyers said they thought so too.

BRANDT SWARDENSKI: It’s always done with the vision of trying to help the individual in front of them. It doesn’t always work out perfect.

Wisconsin Watch and WPR uncovered 52 cases where Biskupic used review hearings to monitor defendant’s behavior or to push them to pay fines, fees or restitution.

BRANDT SWARDENSKI: So the idea was, ‘If I bring them back in and keep reviewing how they’re doing, I can both chastise them when they screw up and praise them when they do well. And hopefully that’ll lead to more success.’

We found that only a handful of judges in Wisconsin did something like this — and Biskupic did it the most by far.

When Swardenski was a public defender, he would tell his clients that by agreeing to Biskupic’s offer to avoid jail time upfront they were, quote, “stepping into a gray area of the law.”

BRANDT SWARDENSKI: ‘And so you’ve got to understand by getting this benefit, you’re subjecting yourselves to further consequences down the line.’

And that’s exactly what happened to Beau Jammes.

Jammes had previously been on probation with the Wisconsin Department of Corrections. But the DOC revoked him for an alleged violation. Typically, at this point, someone in Jammes’ situation would’ve just gotten locked up.

But Biskupic offered a different path — one with no clear ending.

After just a month in jail, Biskupic let Jammes out and ordered him to get a full-time job, attend counseling or addiction meetings, stay sober, take his medications, and work towards a GED. Every few months, Jammes had to return to court to share his progress. Here’s his attorney, Gary Schmidt.

GARY SCHMIDT: Well, it seemed like the judge was trying to use, uh, a carrot. He was dangling a carrot in front of Beau so that he could get better jobs and survive better in society.

In theory, if Jammes did what Biskupic told him to do, he might be able to avoid more jail time. At first, Jammes says, he was happy about it.

BEAU JAMMES: I got to save my apartment. I got to save my home. You know, I got to save what I’ve earned, what I’ve worked so hard for.

I asked Schmidt if he had any idea how long this would last.

GARY SCHMIDT: I did not. I thought maybe the judge was just going to run it for a couple of months to make sure that Beau stayed out of trouble for awhile, and then that would end it, but he kept extending it and extending it.

Schmidt says Biskupic kept moving the goalposts. He initially told Jammes to make progress on his GED. But later, he told him to get his GED.

GARY SCHMIDT: There was always something more that the judge wanted.

Had Beau Jammes just served his jail time, he could’ve been out of jail in about a year. But instead, he endured a 19-month-long legal purgatory.

GARY SCHMIDT: I think the judge wanted to keep Beau under his thumb. I don’t think the judge wanted to just let him walk away.

At the end, Jammes was arrested and convicted by a jury on a disorderly conduct charge. The judge in that case sentenced Jammes to jail. And as a result, Biskupic reinstated his original sentence. Biskupic ordered that the sentence would run concurrent with the one Jammes was already serving. But still, it extended the time Jammes would spend behind bars.

Biskupic did not answer detailed questions about the practice. In a statement, he said he considers all sentencing options, and he also implied he doesn’t do this anymore.

Biskupic’s attorney defended the judge’s actions in an email, insisting that earlier court rulings permit them.

But many of the legal experts and attorneys we talked to weren’t so sure. There wasn’t any statutory authority for this, and so, there weren’t many checks and balances on how Biskupic used this power. Here’s former public defender Brandt Swardenski again.

BRANDT SWARDENSKI: It was, yeah, I think pushing the bounds of the statute to say the least.

Pace University Law professor Bennett Gershman used to be a prosecutor in the New York State Anti-Corruption Office. There, he argued cases against public figures charged with corruption. And, as a scholar, he became a leading expert on prosecutorial misconduct.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: I focus on prosecutors specifically because the prosecutor has the power of life and death. The prosecutor has the power to put innocent people in jail for the rest of their lives. The prosecutor has more power than anybody else in America when you think about it. And many, many prosecutors use their prodigious powers responsibly, professionally, ethically. Some don’t.

I gave Gershman a nine-page summary of issues in seven felony cases Biskupic prosecuted. We talked about most of them in this series. Dale Chu, Mark Price, Jonathan Liebzeit, Ken Hudson, Greg Kortz, Joseph Frey.

And I asked him what he thought about our findings.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: What I saw was alarming. What I saw was conduct that was not isolated, inadvertent, marginal — conduct that one could say was simply mistakes in the heat of battle.

Gershman says Biskupic did the same things over and over again — like withholding evidence.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: This is the kind of conduct you might see in 20 prosecutors, and I’m looking at one prosecutor. And, and the conduct in each of these cases is very, very serious.

The summary I shared with Gershman also included an explanation of Biskupic’s crime prevention fund practice.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: But the justice for sale is absolutely horrendous. I mean, it’s one person who’s, who’s wealthy can buy his freedom and somebody who’s poor can’t. I mean, that’s terrible. I mean, it’s just mind boggling, that that a prosecutor would have something like that, that kind of operation going. It tells you something about the prosecutor, of course.

Gershman and other legal scholars have pointed out, prosecutors in this country face very few consequences for their actions.

And we want to be really clear here. To our knowledge, the system has never formally accused Biskupic — let alone found him responsible — for committing even a single act of misconduct.

BENNETT GERSHMAN: I say the courts and the disciplinary bodies should be ashamed of themselves. As I read every one of these cases, putting them all together, I think it’s a disgrace that the courts and the disciplinary bodies in your state of Wisconsin took no action against this prosecutor. There were no consequences visited upon this prosecutor. I think it’s a disgrace.

I asked Gershman one of the questions I’ve been thinking about, battling with, throughout this series.

PHOEBE PETROVIC: This prosecutor, Vince Biskupic, he was really popular in his district. It was a more conservative district. You know, he’s prosecuting people for egregious crimes. Like, why should those people care? People who liked him as a person, respected him as a prosecutor? Why should they care that he cut corners — particularly if he cut corners to convict someone who is factually guilty?

BENNETT GERSHMAN: You know, Phoebe, that’s a great question. I would say that matters to people who care about fair play, who don’t like to see cheating. And they want somebody who has the power — this tremendous power to hurt people and destroy people’s lives — to use that power responsibly.

And that’s what this is all about. If you care about fair play, you have to care about prosecutors misusing their power. Even if they think they’re doing it in service of the greater good. But on the other hand…

BENNETT GERSHMAN: My guess is that many people in the public won’t care. You know, the end justifies the means. Whatever it takes to put these people away, to prevent these people from committing any more crimes is what, uh, we want to see. I think that’s why it’s so difficult for the criminal justice system to root out bad prosecutors. They can win the approval of the public. And many, many prosecutors all over the country can do that.

I’ve been thinking a lot about what Bennett Gershman said. There’s a good chance that people won’t care about the questionable behavior we found in cases prosecuted by Joe Paulus and Vince Biskupic.

This isn’t new to me. I’ve had prominent people in the justice system tell me: ‘There’s no story here. That guy in that case you’re investigating — he’s guilty.’

And look, some of these cases are horrific — the worst you can imagine.

I know some survivors and family members of violent crimes take solace in knowing that the people convicted of hurting them are locked up and can’t do it again.

But prosecutions have to be done right. They just have to.

There’s just too much at stake. When we hear that prosecutors have relied on faulty evidence, or overcharged or locked an innocent person in a cell, it puts us in danger of losing trust in the justice system.

And this isn’t just about two prosecutors in the Fox Valley of Wisconsin. This is how it works all across the country.

Prosecutors hold so much power: the ability to take away life and liberty.

So I’d like to challenge you to pay more attention to what prosecutors do. You might not care… yet. But I really think you should.