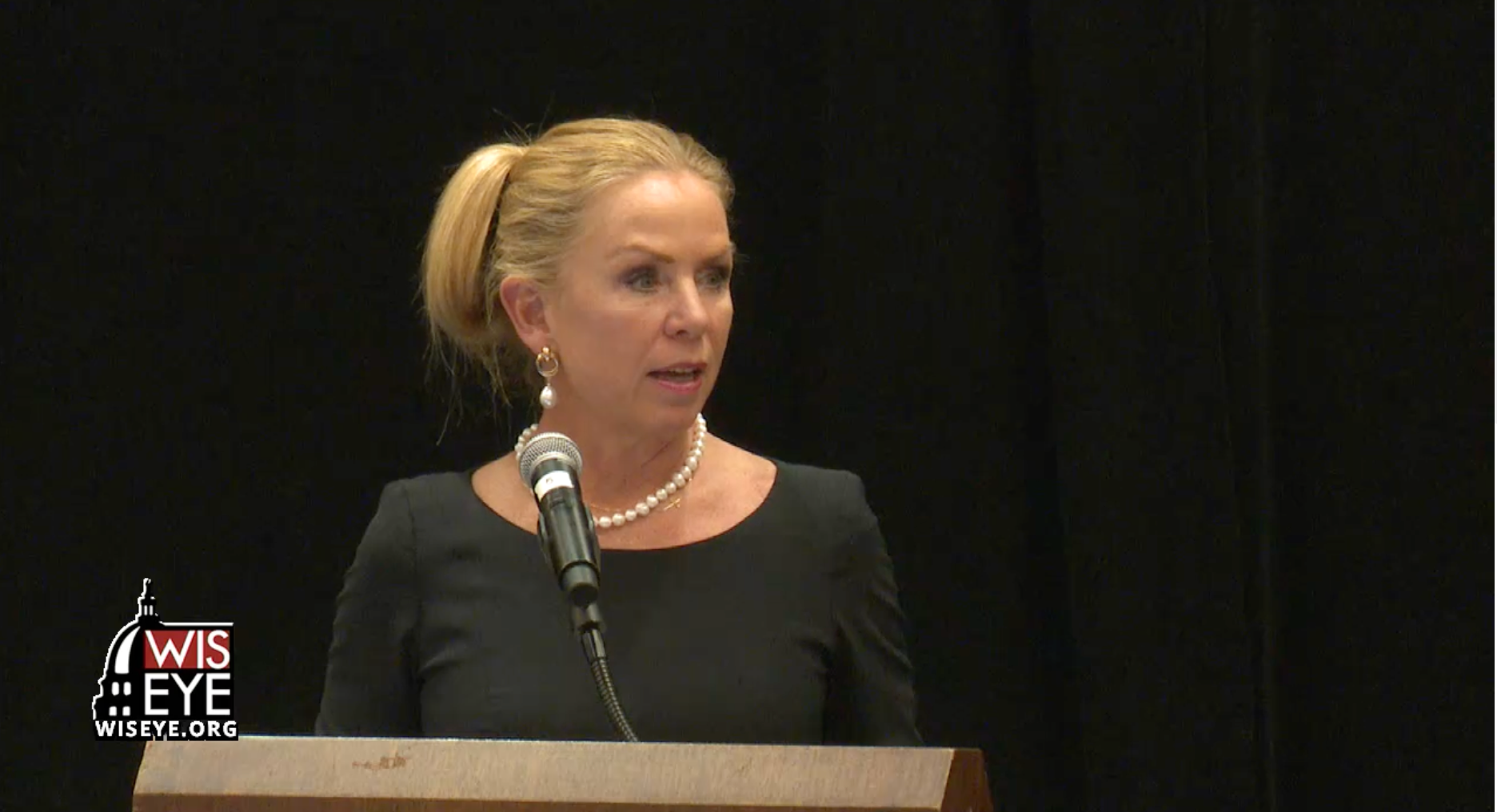

Cassy Rivers remembers nearly everything that happened Aug. 16, 2017.

That day she was driving to a hospital in Oconomowoc to see her husband when she got turned around.

She pulled into the driveway of a home and asked a couple where the hospital was. Instead they asked if they could take her there, and she agreed.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

While in the hospital room about an hour later she was arrested by a Waukesha County deputy for her third OWI.

Her blood alcohol content was 0.34 percent. Wisconsin’s legal limit is 0.08 percent.

“I can tell you I remember most of the night, that just shows you the tolerance I had, and that just didn’t happen overnight. That was years of heavy drinking,” Rivers said.

More than a year-and-a-half later, Rivers calls that third offense a blessing and a turning point because it brought her to the Waukesha County OWI Treatment Court, a treatment program she said has helped her piece her life back together.

OWI treatment courts are known as problem-solving courts. They work with individuals charged with drugged or drunken driving by combining drug and alcohol treatment and the criminal justice system to give participants the tools to change their lives.

Rivers began drinking heavily about nine years ago after receiving some bad news.

Before that day it was “very rare,” Rivers said, that she’d drink. But that day the drink calmed her down “within 30 seconds,” and that memory stuck.

“Any time there was some kind of stress or bad news, it was like my go-to,” she said.

For the coming years, Rivers drank on a nearly daily basis. It got to the point where if she didn’t drink, she’d tremble.

She didn’t party.

She didn’t go out with friends or family to a neighborhood bar.

She would sneak alcohol, typically liquor.

Her first OWI was in 2013, her second in 2014.

During those nine years of heavy drinking, Rivers would leave her job of 20 years because of the absences that were adding up, her husband would file for divorce, and she’d miss the high school and college graduations of her twin daughters.

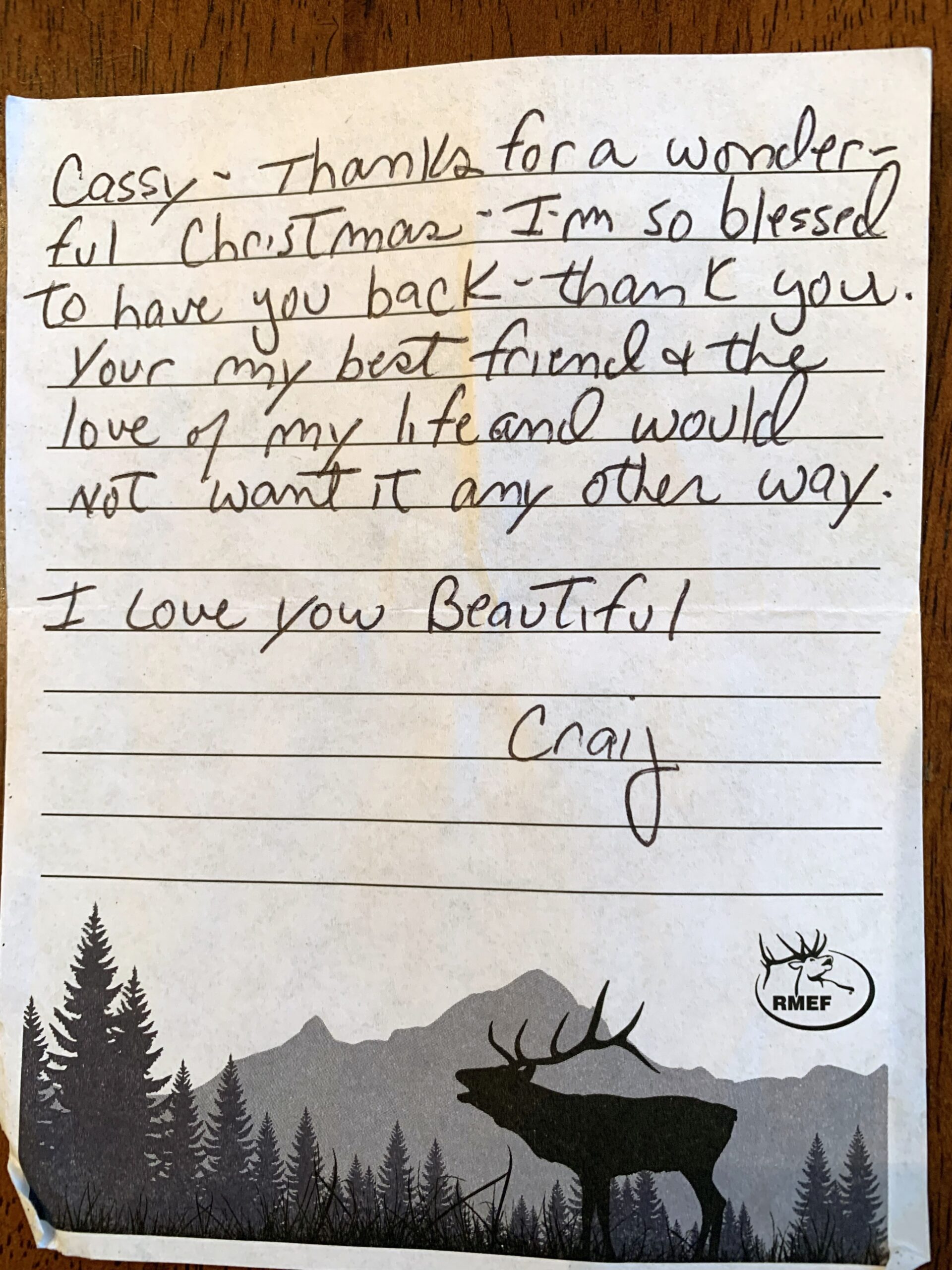

In 2016, Rivers received a text from one of her daughters sent on behalf of both “basically disowning” her, she said. It was addressed to “Cassy” not “Mom.”

Before her third OWI, Rivers listened to pleas from family and friends to stop drinking.

She’d been hospitalized nine times to detox, had done outpatient and inpatient treatment, including two 30-day programs and one 50-day program. There were “brief times” of sobriety, she said, but nothing lasting.

Rivers is what treatment court professionals would call high-risk, high-need. Someone who is dependent on a substance and likely to fail in less intensive treatment programs.

‘This Is How We Should Be Treating People’

The goal of OWI court is to reduce recidivism rates, reduce participants’ substance use and provide rehabilitation to participants.

A team that includes representatives from across a county — a prosecutor, defense attorney, judge, law enforcement, social service caseworkers, treatment providers and probation and corrections officers — works together to hold participants accountable for their own sobriety and transformation as well as society’s safety.

The incentive? Getting clean and reduced time behind bars.

The program is not a get-out-of-jail free card. It’s intensive.

The team of trained professionals works closely with the participants struggling with addiction.

Among the requirements for participants are mandatory court appearances, recovery meetings, counseling and random alcohol and drug testing.

The community-based treatment court model has been around since the late 1980s, and was born out of the growing number of drug cases, according to a study posted on the U.S. Courts website.

Wisconsin’s first OWI court opened to participants in 2006 in Waukesha County.

Waukesha County stakeholders began seeing a rise in drunken driving offenses and wanted to see if the program could help bring that number down while reducing the incarcerated population, said Rebecca Luczaj, Waukesha County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council coordinator.

People who have been convicted of nonviolent third- and fourth-offense drunken driving are eligible for the county’s program.

Participants typically complete the program in 12 to 14 months, Luczaj said, though it can take longer depending on the participant’s progress or if they face a sanction, such as a night in jail or community service, for a violation like drinking or missing a drug test.

The county’s program is post-conviction, meaning a participant can only begin after a judge has sentenced them and they’ve served their required jail time. A participant with a third or fourth offense is required to spend 30 or 60 days in jail, respectively — far less than what they would serve if they didn’t participate.

There are 31 treatment courts serving OWI offenders in Wisconsin, according to the state Department of Justice website. And there are more than 700 treatment courts serving OWI offenders across the United States, said Jim Eberspacher, division director of the National Center for DWI Courts (NCDC).

Individual courts can decide the population they want to serve and how the court is structured so long as they follow national guidelines — including the 10 Guiding Principles of DWI Court from the NCDC and best practice standards from the National Association of Drug Court Professionals — and state guidelines — including the Wisconsin Treatment Court Standards.

The flexibility given to the courts allows local stakeholders to tailor programs to their community, and it’s effective, according to the DOJ.

Treatment court advocates and experts say services offered in jails and prison don’t effectively treat addiction.

“The crux behind the crime was their addiction and that’s what we’re trying to address. It’s a disease.”

Tammy Simmons, treatment court coordinator for the La Crosse County OWI court

Most people arrested for drunken driving don’t repeat the offense, but 25 percent do become repeat drunken driving offenders; and almost half repeat OWI offenders have a diagnosable substance use disorder, according to a National Drug Court Institute (NDCI) June 2016 report.

“The crux behind the crime was their addiction and that’s what we’re trying to address. It’s a disease,” said Tammy Simmons, treatment court coordinator for the La Crosse County OWI court, which was the second to open in the state and serves first offense and higher.

Eberspacher, of the NCDC, said a “cookie cutter” approach in the justice system is ineffective. Incarceration may make some people feel better, but it’s not changing a behavior, he argued.

People who complete treatment court are 19 times less likely to commit another crime, according to the NCDC.

According to the June 2016 NDCI report, OWI courts have “significantly better outcomes … compared to standard or intensive probation or adjudication as usual. On average, DUI courts were determined to reduce DUI recidivism and general criminal recidivism by an average of approximately 12 percent. The best DUI courts reduced recidivism by 50 percent to 60 percent.”

In 2013, the National Transportation Safety Board endorsed OWI courts as a “proven” way to rehabilitate repeat drunken drivers, reduce recidivism and reduce the number of vehicle accidents.

“When I got involved for the first time and saw people actually change and get well and get into long-term recovery and not come back into the system again, I was sold on it, I was like ‘I’m done with traditional probation,’” said Eberspacher, who began his career as a probation officer in Minnesota. “This is the way, this is how we should be treating people.”

Advocates also say these courts save taxpayer dollars by keeping people out of jail and contributing to society.

A cost-benefit evaluation of OWI courts in Minnesota showed that on average, treatment courts create up to $3.19 in return for every $1 invested.

Wisconsin treatment courts can be funded by state, federal and county money.

The state began providing funds for the courts through the state Treatment Alternatives and Diversion (TAD) Program established in 2005 and administered by the DOJ and other state agencies.

The TAD program has expanded from seven counties using $700,000 in grants to 50 counties and two tribes using $6.5 million in grants, according to the DOJ.

In 2017, the DOJ launched a system that collects data for treatment courts and diversion programs throughout Wisconsin in order to gather more detailed data on participants, monitor programs’ progress and track outcomes. That information will be used to create an updated evaluation on treatment courts at the end of 2019.

In Waukesha County, the court started out as grant-funded and serving only third-offense offenders. In 2010, a federal grant allowed the county to expand to fourth-offense offenders. Since the grant ended in 2014, the program has been entirely tax levy funded.

The cost to run the program in 2018 was about $152,000. In 2018, it cost $1,998 per OWI court participant, Luczaj said.

The daily cost to keep someone in the county jail was $100.73 in 2013, Luczaj said, citing a 2014 Waukesha County Jail audit.

According to the DOJ, TAD programs have saved millions of dollars in prison and jail costs and “graduates were significantly less likely to be convicted of a new offense within one year, two years and three years after completing a TAD program (and) 81 percent of TAD graduates did not have any new convictions after three years.”

Your Biggest Cheerleaders

The structure, duration and accountability of treatment court is exactly what Cassy Rivers needed.

After serving a 30-day jail sentence, the 47-year-old began the intensive program in February 2018 and completed it in February 2019.

It wasn’t easy for Rivers.

The random testing, weekly meetings and court appearances every other week were demanding. She had to do community service and find a job. And staying sober was challenging. The first month of the program Rivers drank.

Rivers spent the night in jail and had to wear a bracelet that continuously monitors a person’s blood alcohol level.

“I’ll never forget Kristy, the director of the OWI court, she came to me and said, ‘You know, this isn’t meant to punish you, it’s meant to help you,’ And that was the turning point where I totally surrendered and I thought ‘That’s ATC in one sentence,’” Rivers recalled of the program, formerly known as Alcohol Treatment Court.

The atmosphere in treatment court hearings is likely one of the first things an observer would note as different from traditional court proceedings.

The judge, while not your friend, jokes with you. The judge, while caring about your recovery and sensitive to the challenges, will give you a sanction for drinking or being late.

It’s tough love, and it’s intentional.

During a Waukesha County OWI court hearing in April, the staff found out a participant allegedly drank and drove — an automatic ejection from the program. The participant was sent to jail for a week until a hearing where he was discharged from the program.

The mood in the room was serious. It was a reminder to participants sitting in the courtroom gallery of what they’re risking if they fail or drop out of the program: the remainder of their jail or prison time.

But the team that works with OWI court participants also openly celebrates accomplishments made by the recovering addicts: a new job, a visit with children, 19 days of sobriety, a repaired relationship.

John Collins is in the Waukesha County OWI court and said he truly believes his treatment court team members are his biggest cheerleaders.

He began the program in October after pleading guilty to his fourth OWI in September.

Collins, 38, didn’t want to admit he has alcoholism until he got his fourth OWI.

His first three OWIs came when he was in his 20s, a time, he said, when he was more concerned about himself than others.

For Collins, his biggest challenge is complacency.

He stayed sober for several years after his third OWI but stopped going to his Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and fell back into the wrong crowd and bad habits.

There is a history of alcoholism in Collins’ family, and he ignored some of the pleas from his family and friends to change his ways. After his fourth offense, his mother didn’t talk to him for almost six months.

When he was sitting in jail before starting treatment court, he said he thought long and hard about his mistakes and not just about what he wanted in a future, but that he wanted a future period. He wanted to live.

“In the recovery community we say that if you continue to use, the ultimate result is going to be jails, institutions or death; and I was living that realization,” Collins said. “So that’s where I kind of had my moment of clarity, that’s where I felt I had finally hit the bottom and realized that I need to do this, I need to make changes, and I need to do it now.”

Participants and graduates credit their life changes to their sobriety and the program.

During Rivers’ time in the program she became employed, and that was celebrated during a treatment court hearing by the judge, the same judge that convicted her.

“This team, they didn’t just care if I was drinking, they cared about what I was doing,” Rivers said. “They cared about my life.”

“In the recovery community we say that if you continue to use, the ultimate result is going to be jails, institutions or death; and I was living that realization.”

John Collins, Waukesha County OWI court participant

‘This Program Changes Lives’

From the time Waukesha County’s OWI court began through March of this year, it had 599 participants, and 441 of those have graduated. It has a 78 percent success rate, something Rebecca Luczaj, the coordinator, said the county and treatment court staff are proud of.

Since the Waukesha County OWI court began, eight people have been charged with a subsequent OWI while enrolled in the program.

Collins said if he hadn’t chosen treatment court, he’d be incarcerated, sitting on a lot of anger, resentment and fears, and likely returning to society with baggage that would lead him right back to drinking.

Instead, OWI court has taught him how to address difficult situations and handle stress in a healthy way.

“I’ve watched people graduate here through the ATC program and when they get up there, and they talk, and they have their wife or their significant other or their children in the back and they well up and they start crying, those emotions are real; I mean, they’re very real. This program, it changes lives,” Collins said.

When Rivers “totally surrendered” to OWI court and began being honest she started to see change, she said.

Since Rivers began the program, she has repaired her marriage with her husband, found employment, is 13 months sober, and, maybe most important to Rivers, has reunited with one of her daughters, and hopes to repair her relationship with the other.

Rivers’ transformation is a success for Kristy Gusse, program director for Wisconsin Community Services which handles case management for treatment courts. For Gusse, success in OWI court isn’t formulaic, it’s different for every participant.

It could be repairing a relationship destroyed because of alcohol, obtaining a GED or graduating from the program.

On the day of Rivers’ graduation in February, her husband was there, and her OWI court team and peers celebrated her graduation certificate – a piece of paper signed by team members that is a physical reminder of what Rivers has been through.

“When I received the certificate, the graduation certificate, I felt like I was getting an Academy Award,” Rivers said. “I mean that’s how much of what I thought was impossible, I had, I finally had — not the certificate — I had sobriety.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.