Segdrick Farley had a toothache, but he didn’t have $7.50.

It was early 2020. He was a few months away from completing 21 years spent in various Wisconsin prisons. He was in pain — a lot of pain. He said for about a week, he was putting in request after request to receive medical attention for his tooth.

“If you’ve had one, it’s really painful,” he said of the toothache. “I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

He didn’t have the $7.50 to cover the copay for a prison medical visit, and he said his requests to be seen had been denied. Perhaps prison officials didn’t consider this toothache an emergency, but it sure felt like one. He said someone told him to try and act like he fell. Eventually, when a correctional officer walked by, Farley laid on the ground, pretending he couldn’t move.

“I had to take that drastic step to get some medical care,” Farley said.

He was finally seen — about a week and a half after the aching started — but the pain lingered, as did the money he owed for the medical care.

Farley isn’t the only incarcerated person to become desperate for medical care and not have a surefire way to pay for it. The copay might not seem costly, but criminal justice reform advocates point to low prison wages and the costs associated with other matters, such as phone calls, that mean the dollars add up fast.

Farley comes from poverty.

He’s from Milwaukee, where he also spent the first eight or so months after his release from prison two years ago. He lives in Eau Claire now, where he’s still working to pay back what a judge decided he owes in court costs, restitution and other fees, as well as about $200 in medical debt from his incarceration.

“That perpetuates poverty because it follows you out here into the world,” he said.

Some states suspended all medical copays during the pandemic; but in Wisconsin, at the start of the pandemic, the state Department of Corrections suspended medical copays for incarcerated people who suffered from COVID-19 or other respiratory symptoms. That policy ended March 7. Other states have reverted to pre-pandemic policies, as well.

Ten states, most recently California and Illinois, don’t charge incarcerated people copays at all, and another, Virginia, has a pilot program for suspended copays, according to a February analysis from the nonpartisan Prison Policy Initiative, a group that advocates for ending mass incarceration.

That same analysis points to two “inevitable and dangerous consequences” of unaffordable copays: Untreated illnesses can spread further inside prisons and out in the community, and untreated medical problems can worsen over time and ultimately become more expensive to address — for people in prisons and the taxpayers who fund them.

READ MORE: Incarceration after COVID: How the pandemic could permanently change jails and prisons

Criminal justice reform advocates are asking if Wisconsin’s policy should go further. In interviews with Wisconsin Public Radio, a half dozen formerly incarcerated people applauded the suspension but said the DOC shouldn’t have medical copays at all, or at least the department should raise wages for incarcerated people or make copays more affordable.

At $7.50, Wisconsin has one of the highest prison medical copays in the country, according to state-by-state data the Prison Policy Initiative gathered in 2017, although there are some exceptions to get out of paying.

Those interviewed shared how much $7.50 is worth to incarcerated people whose jobs might pay nickels and dimes per hour. They gave a glimpse about what it’s like to choose between paying for medical care and getting some toiletries, calling home or filing documents for court appeals.

How much is $7.50?

Marianne Oleson knows $7.50 doesn’t sound like a lot of money. She is the Fox Cities organizer for EXPO Wisconsin, short for EX-Incarcerated People Organizing.

But prior to going to prison, she didn’t understand what $7.50 really meant to those who were incarcerated. In prison, she worked as a janitor and in the kitchens. She said the prison jobs she saw brought in, at best, between $0.19 and $0.33 per hour. Fortunately, she said her husband stood by her and helped her financially, so she could escape the excruciating financial decisions she saw fall upon some women around her. Choices like: Should I buy laundry soap or try and see a nurse because I think I hurt myself?

“That was a difficult, agonizing choice that I don’t think anyone in Wisconsin would want their mothers, daughters or sisters having to do,” she said. “That’s a scary thought, and I watched it happen over and over.”

Farley, who worked as a baker, cook, dishwasher and janitor, said 60 percent of his paycheck got taken out for various court costs, leaving him making $8.94 every two weeks or $9.94 if he was able to get in some extra hours.

“I’m getting paid barely peanuts to take care of myself,” he said.

Wisconsin law says prison wages, “provide uniform and fair compensation standards to encourage and reinforce positive inmate behavior.” The wages also let people buy items from the canteen, save money for after their release and develop work skills, according to state statute.

Prisons can rank their jobs based on how much skill or responsibility is involved and pay more or less depending on the ranking.

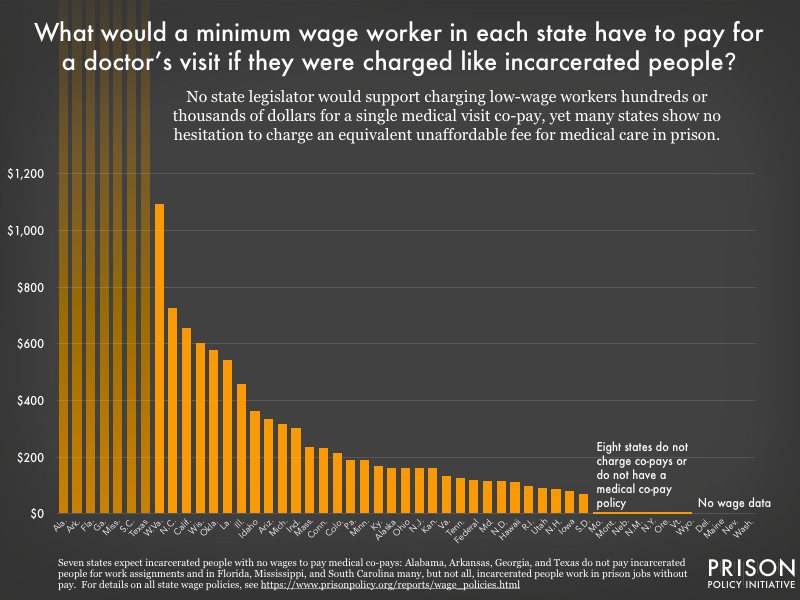

In 2017, the Prison Policy Initiative published a story that estimated how much a medical copay would cost a minimum-wage worker in each state if they were charged at the same rate incarcerated people are. In Wisconsin, it was about $600.

Dennis Franklin — the leader of EXPO Triage, a program helping those on probation and parole — said he was having to get by on $11 a month while he was in prison.

“It can put a person in a state of hopelessness because how do I afford just the basic cosmetics?” he said. “We’re not even talking about any pleasantries. We’re just talking about deodorant.”

And needing medical attention while incarcerated can be terrifying.

Franklin vividly remembers May 3, 2018, when he woke up at about 2:30 a.m. with severe chest pain and difficulty breathing. He said it took multiple attempts asking to be seen by a nurse or doctor until he finally made it to a hospital for tests that showed inflammation of the lining of his heart. He eventually got medication. But he said the whole process took far too long.

“Just thinking back on it, it angers me,” he said.

DOC spokesperson John Beard said in an email that prisons supply basic toiletries, such as some soap, shampoo, deodorant and toothpaste, to the prison population. He added that some people prefer name brands, with prices that can range from $0.11 for a 3-inch toothbrush to $8.85 for Axe brand shower gel and shampoo.

Solutions proposed

Ramiah Whiteside had asthma when he was younger. As an adult, he continued to have flare-ups that sometimes required immediate medical attention. Now, the associate director for EXPO thinks back on the moments he struggled to breathe during his 25 years of incarceration.

He also reflects about the people in prison who experience chest pains or asthma attacks in their cells. If they don’t have a cellmate, they could go several minutes before a guard or someone else notices and gets help. It’s not always possible to scream or bang on the door, especially during a time when “each breath is crucial,” he said.

“It’s one of the most terrifying experiences ever because if there is no one there to acknowledge or assist you and get you help, you think you’re going to die,” Whiteside said. “Each breath gets tighter and tighter.”

The DOC doesn’t charge copays for follow-up appointments that are “determined and scheduled by a health care provider.” Whiteside said that policy and the decision to suspend some copays during the pandemic were decisions worth applauding.

But he said moves like that suggest the department has room to make the policy changes it wants.

“At the end of the day, the priority is the person’s health,” he said. “So, putting them in debt with the copay unnecessarily doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

Beard, the DOC spokesperson, declined to make someone from the department available for an interview about their copay policy, the suspension decision and why they chose not to suspend copays for all medical needs.

Whiteside said the “bare minimum” DOC should do is to keep the waiver in place for so-called COVID-19 long haulers. He also said he wants to see a greater flexibility for incarcerated people who are deemed indigent to receive care without having to cover the $7.50 copay.

Melissa Ludin, the regional organizer for the Smart Justice Campaign through the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin, said if copays aren’t made lower, then prison wages should be raised.

But building political support for the rights of incarcerated people might be challenging. Appeals that consider the financial implications of these policies have sometimes attracted bipartisan support.

In fiscal year 2019, DOC reported health care expenditures of about $32 million for hospitalizations among its prison population and about $31 million for pharmaceutical costs, according to a 2020 report to the Joint Legislative Audit Committee. And if incarcerated people are skipping preventative care because they can’t cover copays, that could lead to more expensive treatment later.

The DOC is responsible for “costs incurred at hospitals or clinics unless an adult in custody is formally admitted … by the health care facility,” the report states, adding that the state can get some support under Medicaid through the federal Affordable Care Act.

Franklin said incarcerated people are in the care of the state, so it didn’t make sense to him that they would be charged for medical needs. But he does acknowledge arguments to the contrary. He said he can understand the point that having to pay for such services “sets you up on the path of being responsible.” It can help teach people about managing money and setting priorities.

He also considered the point that without any copays, incarcerated people could overwhelm the prison medical system, inundating staff with too many requests and generally “abusing the health care services unit.” But he said those claims are “overplayed and overstated.”

Fear

Farley was still in prison during the first month or so of the pandemic. His tooth still hurt, but he had bigger worries: Jails and prisons were particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 outbreaks. Through his work as a janitor, he got gloves, masks and whatever else he thought could keep him safe.

“I was scared,” he said.

Farley, who now runs a voting rights group called Brighter than Sunshine, made it out of prison without catching COVID-19. But he was entering a pandemic world after two decades behind bars. When he was released in early May 2020, he said it felt like he was entering a zombie movie.

That didn’t matter, though. He had his freedom.

“My worst day out here is better than my best day in there,” he said.

He was hoping his brother could be with him, even on those worst days. But Alvin L. Simmons, 36, died in March 2021 of a COVID-19-related illness while incarcerated.

When Simmons got sick, Farley was angry. He’s still angry. He asks himself: Did his brother get the treatment he needed? What more could anyone have done before his brother died in his cell?

He wants to make sure people who are incarcerated get the medical care they need and deserve. He wants to be a voice for those left unheard. He said often, people who break the law and make mistakes in their life pay for those mistakes in other ways.

“It turns into abuse of authority,” Farley said. “I remember being afraid, and I just imagine how afraid my brother was. He was afraid. He put on a front of strength. But I know my brother was afraid because I would have been afraid.”

He felt helpless to his brother, so he wants to help others. He appreciates the support system he still has. For those who do make it out of prison, he doesn’t want their lives derailed by medical debt.

“You don’t want to come home in poverty and debt and having to start over,” he said. “I’ve just been fortunate enough to have some great people around me. That’s been the difference. A lot of guys don’t have that.”

Update: This story was corrected on Nov. 16, 2023, to reflect that a state Department of Corrections spokesperson said a previous department spokesperson incorrectly told WPR the suspension of medical copay for COVID-19 and respiratory symptoms was still in place at the time of this story’s publication. The DOC lifted the suspension March 7, 2022.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.