At the end of each year, all the Filipino moms at our family New Years’ Eve party would break out this tile game with all these Chinese symbols — mahjong. They’d play for hours, always screaming and laughing like Filipino moms do, sometimes playing until the wee hours of the morning. I didn’t get it until about a year ago, when all the moms taught the kids in my family. Now, I’m addicted.

In essence, mahjong is a matching game similar to rummy, but instead of cards you have these ornately carved block tiles. You could be forgiven for thinking the game has ancient ties to Chinese culture — that was a major part of how it was marketed to Americans in the early 20th century. But truthfully, the game is fairly modern.

According to historian Annelise Heinz, the game emerged in the late 19th century and was played mostly by Chinese men in courtesan houses and social clubs in cities like Shanghai and Beijing. But after World War I, more and more Americans started coming over to China to do business, including Standard Oil businessman Joseph Babcock.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

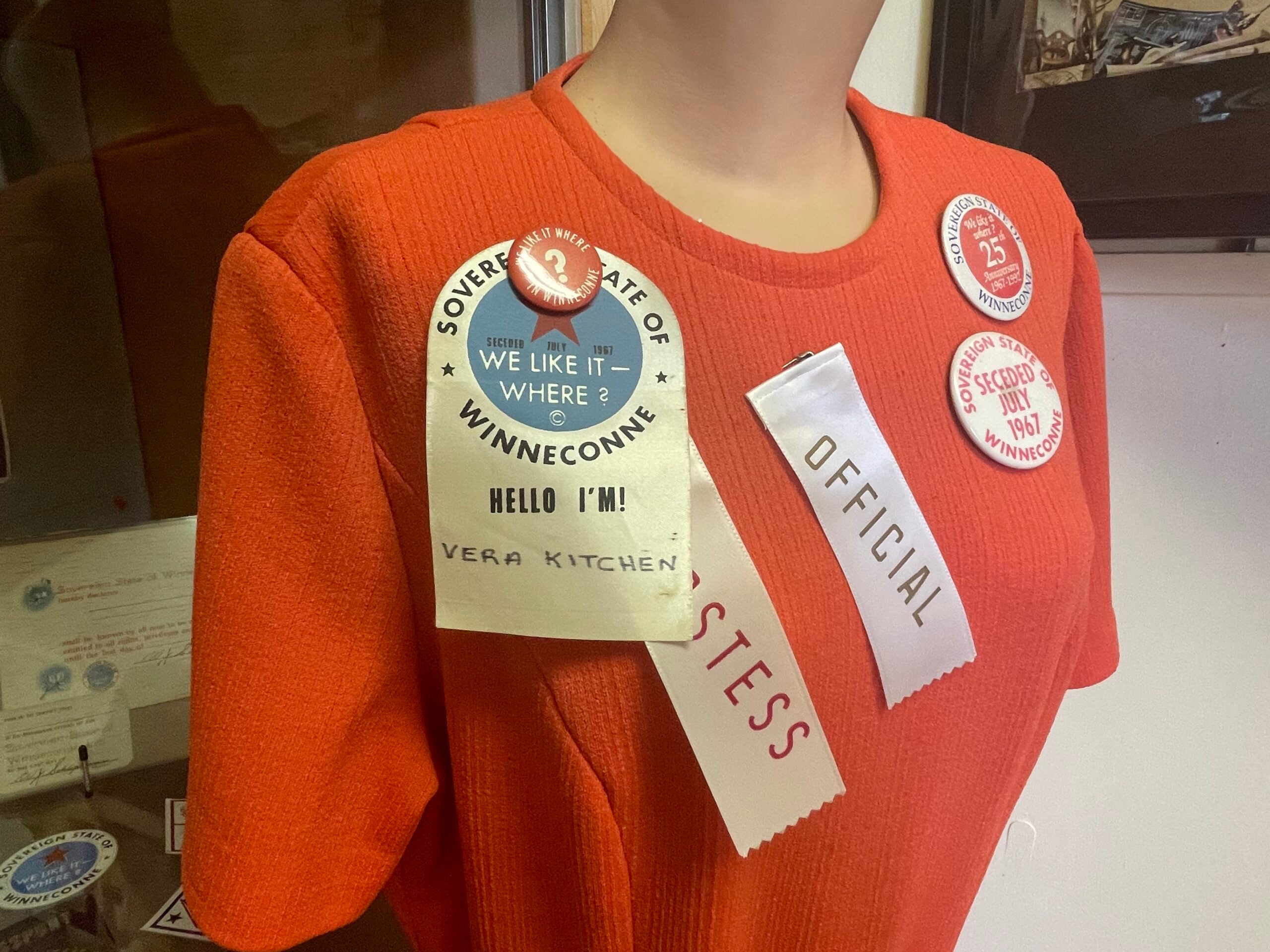

Babcock’s book of rules. Angelo Bautista/TTBOOK

Babcock founded the Mah-Jongg Sales Company and started importing thousands of dollars worth of mahjong sets. He wrote his own book of (simplified) rules. He even tried to patent the game as his own invention. Heinz says that in the United States, the game was marketed primarily to wealthy white women. And this made a lot of sense, because they could afford these very fashionable, handmade sets and had the leisure time to play.

By 1937, the game had fallen out of favor in the cultural zeitgeist, but it was taken up instead by a group of Jewish-American women that wanted to bring mahjong back. Heinz says that by the end of World War II, mahjong had become an integral part of Jewish social life — Jewish American families were moving to the suburbs in greater numbers thanks to the G.I. Bill and access to housing loans, which was isolating to many Jewish women. Regular mahjong games with neighbors and family became their new social network.

And all the while, mahjong retained its status as a Chinese game, a staple of gatherings of Chinese Americans all the way up through today, even breaking back into the cultural zeitgeist as a part of books like “The Joy Luck Club” and films like “Crazy Rich Asians,” as broken down by cultural critic Jeff Yang.

By the end of the 20th century, mahjong had acquired a whole litany of identities. But what’s unique about mahjong is that it’s not just one thing. It is a Chinese game, no doubt. It always will be. It’s also a Jewish game, an American game, a Filipino game, and so much more. Over a hundred years, in the hands of different players, it’s a game that has taken on so many different histories, including my own. And as long as we’re playing mahjong, that history is still being written.