The Rev. Joseph Fisher was in the middle of his Palm Sunday sermon when the police came.

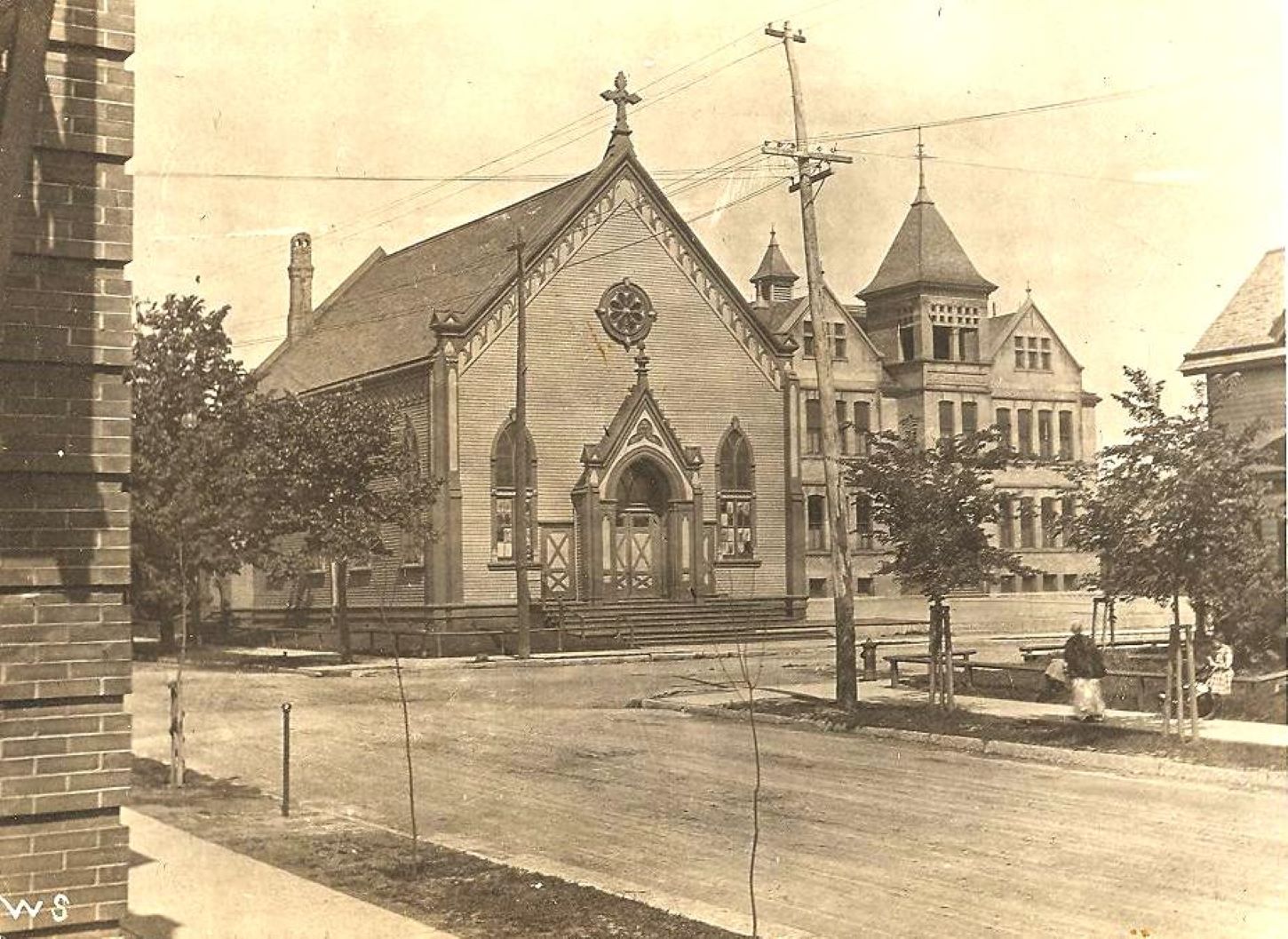

The pastor at Pilgrim Lutheran Church is used to preaching to hundreds of congregants at his West Bend church, which has about 700 members. Since Gov. Tony Evers’ stay-home order went into effect in March, they’ve strictly limited in-person attendance to no more than 18 people in two separate rooms, all sitting more than six feet apart.

That didn’t stop a neighbor from calling the police to report the gathering. West Bend officers on Sunday told Pilgrim Lutheran pastors that they were in violation of the governor’s order and made the members and Fisher’s associate pastor leave.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The moment was caught on the church’s YouTube video of the service, which is the way most of its congregation has been participating in services. Around 30 minutes into the video, Fisher stops to respond to a member who tells him the members are being made to go home. “Everyone?” he asks.

The moment is an example of the still-unsteady relationship some faith communities have with government efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19. As Christians prepare for Easter weekend and Jews observe Passover, it’s also an example of how, even amid unprecedented adaptations by religious communities, there remain points of friction in a time of quarantine.

On Thursday, the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty in a letter to Evers asked the governor for “immediate clarification” about whether the state’s order also bans outdoor, drive-up religious services. Evers, whose “safer-at-home” order explicitly designates “religious entities” as essential businesses, in a Thursday press release said drive-in services were permitted under the order — as were gatherings of 10 people or fewer in a room.

Fisher called the shutdown of his church’s Palm Sunday service a good-faith “misunderstanding,” and said West Bend police later apologized to him and acknowledged that Pilgrim Lutheran services were being conducted lawfully. Fisher stressed that the church is taking precautions such as sanitizing hymnals and refraining from serving communion at the church’s altar.

“I think it’s a situation where we weren’t doing anything wrong, the police didn’t do anything wrong and the neighbor didn’t do anything wrong, and yet it made a story,” Fisher said in an interview with WPR, referring to the online reaction to the event.

Still, many churches and other faith communities have opted to cancel in-person services entirely, relying on the same online meeting tools employed by private businesses to keep connected during a time of social isolation.

In March, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee announced that its in-person Easter and Holy Week services would be canceled. Pastors throughout the state have done the same, using video services, podcasts, Facebook broadcasts and other adaptations to remain connected to their communities. In Baldwin, Peace Lutheran Church launched a drive-in worship service of the sort that, per Evers’ Thursday statement, is allowed.

But even though many churches have changed their practices, the back-and-forth between the conservative think tank and the governor is one piece of evidence that there has been some conflict between some religious and political leaders and the public health advice that all residents keep their distance from social interactions.

On Friday, Assembly Republicans called on Evers to suspend social distancing requirements for religious communities in order to allow Easter and Passover services to go forward. Evers declined that request, expressing sympathy for faith communities, but calling the restrictions necessary “in order to protect the health and safety of all Wisconsinites.”

A similar dynamic has been apparent in local health departments, as well.

In Marathon County, the health department’s public information officer issued a statement saying “government and faith communities throughout Wisconsin need to work together to stop the spread of COVID.”

“We can sympathize with the religious entities that the services are different,” read the statement from public information officer Judy Burrows, but “social distancing and avoiding direct contact with others is the only effective means of reducing the spread of COVID.”

In Douglas County, health officer Kathy Ronchi also expressed sympathy for faith communities but recommended against in-person gatherings.

“This is a challenging time for all and we have to make big sacrifices for a little while to protect the health of our community,” Ronchi said. “We look forward to the day we can again allow in-person gatherings to take place. In the meantime, we ask that you stay connected with one another through phone calls, video chats, text messages and other ways.”

For some faith communities, especially minority faiths, those online options come with their own risks. Nationally, some synagogues have experienced “zoombombing” attacks by racist and anti-Semitic groups during their online services. And not all members of all communities have access to online services. Fisher noted that about 100 of Pilgrim Lutheran’s members have no internet at home.

Fisher stressed that he doesn’t view Evers’ safer-at-home order as a restriction on the free expression of religion. Nor he is interested in flouting the law — as, for example, a megachurch pastor in Tampa, Florida recently did.

“We’re trying to make sure that we don’t hurt anybody,” Fisher said. “But we’re also trying to care for our members.”

This weekend, they’ll hold Easter services at 6 a.m. and 8 a.m. Sunday, he said, and the first 18 people who show up can attend in person, in two separate rooms.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.