A new bill that would change how the state distributes funds to local communities also comes with a two-line provision that would prohibit a town, city or county from holding an advisory referendum.

Advisory referendums are nonbinding questions for voters. They gauge public opinion on issues. Activists from across the political spectrum have used them to demonstrate that there is popular support for — or opposition to — anything from abortion rights to local transportation measures.

But while both sides of the aisle have used them, these types of votes are on the chopping block in the GOP-authored shared revenue proposal, unveiled earlier this week. Left-wing activists say this will cost them a key tool for promoting their agendas and engendering bipartisan support for certain projects, like changing the state’s legislative maps.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Speaking to reporters at a luncheon on Friday, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, said that the voting booth is not the place for interest groups to weigh in on local politics.

“That’s not the point. That’s what elections are about,” he said. “We should have had advisory referenda only for things that are directly related to what is being done that municipality.”

Gov. Tony Evers has said he will not sign the bill as written, saying it does not support communities enough and comes with too many strings attached. The bill went through a committee hearing on Thursday, and is expected to go up for a vote this week.

“It’s flouting the will of the people and trying to silence our voices,” said Carlene Bechin. She recently retired as organizing director for the Fair Maps Coalition, a group that advocates for changes to Wisconsin’s legislative maps. She said one of that group’s central strategies was to get advisory referendums on county ballots.

“I’ve been so hopping mad about this. I mean, when I heard about (the provision), I just went through the roof,” she said. “It’s like, ‘You’ve got to be freaking kidding me.’ Only, that’s not what I said.”

Wisconsin is one of 24 states where voters cannot directly add binding initiatives to ballots, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Instead, activists say that these nonbinding votes are a launchpad from which to gather data and present public pressure to elected officials.

Matt Rothschild, of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, says they’re an important tool for voters to communicate with their elected representatives. In written testimony he submitted Thursday to a government committee, he called the provision “a blatant violation of the Wisconsin Constitution and a slap in the face to every citizen of this state.”

“You are telling all of us that you don’t even want to hear from us, and that we can’t even express ourselves in advisory referendums on public issues through our local governments,” he wrote.

Critics of these referendums say they can threaten representative democracy by allowing voters to determine the priorities they’d already elected people to set. They also argue these referendums are used to juice up turnout in low-key elections, rather than to meaningfully effect policy.

Advocates say advisory referendums help them educate voters, push for changes

Gary Storck has been an advocate for medical and recreational marijuana use for more than 50 years. He said referendums helped track how support among Wisconsinites for cannabis use has grown over the decades. They also can demonstrate when an issue has wide bipartisan support, he said. Cannabis-related referendums in recent years have passed overwhelmingly in red, blue and purple counties.

He also said organizing around referendums starts conversations among citizens.

“It’s created an opportunity for citizens to discuss the issue with their friends and neighbors and co-workers and family because it was in the news,” he said of a series of county-level referendums that passed in 2018. “A lot of Wisconsinites found out that, yes, everybody they know supports this.”

Bechin, the legislative maps organizer, said referendums are a tool for educating voters and lawmakers alike.

“We have used referendum as educational tools to let people know about the gerrymander,” she said. “By using referendum, we can talk about just how gerrymandered our maps are, and also send a message to those same legislators that says, ‘Look, this is what this is what the voters want.’”

And while some of those referendums pertained to hot-button issues, they’re often centered around issues of highly localized concern, said Richard Loeza, a legislative analyst in the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Research Bureau. This spring, he said, during the high-profile judicial race, many voters were also asked to weigh in on whether all-terrain vehicles should be allowed on their local roads.

According to Rothschild, 32 counties and 21 municipalities have passed referendums related to those maps. But activists from across the political spectrum have used advisory referendums to advance their agendas.

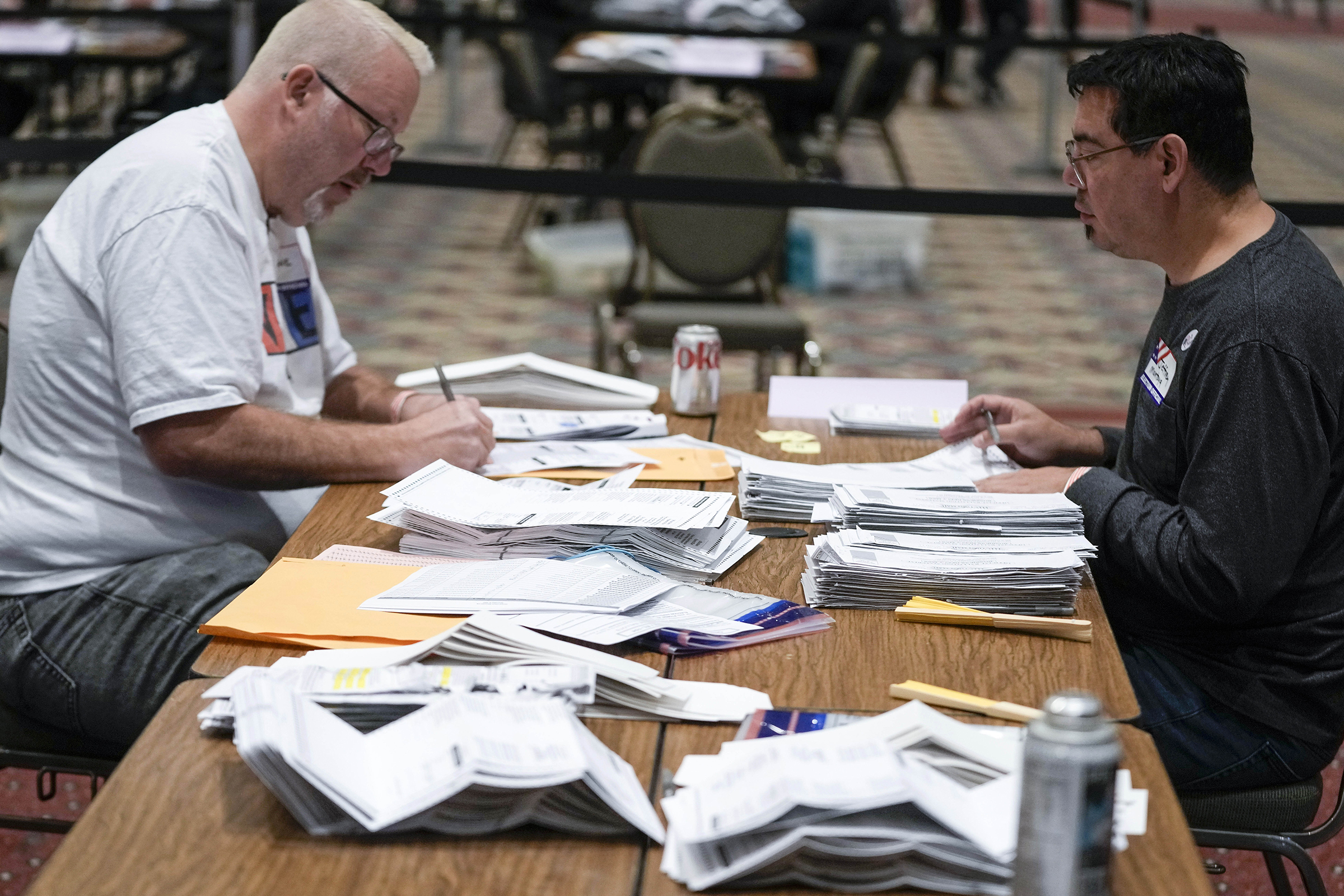

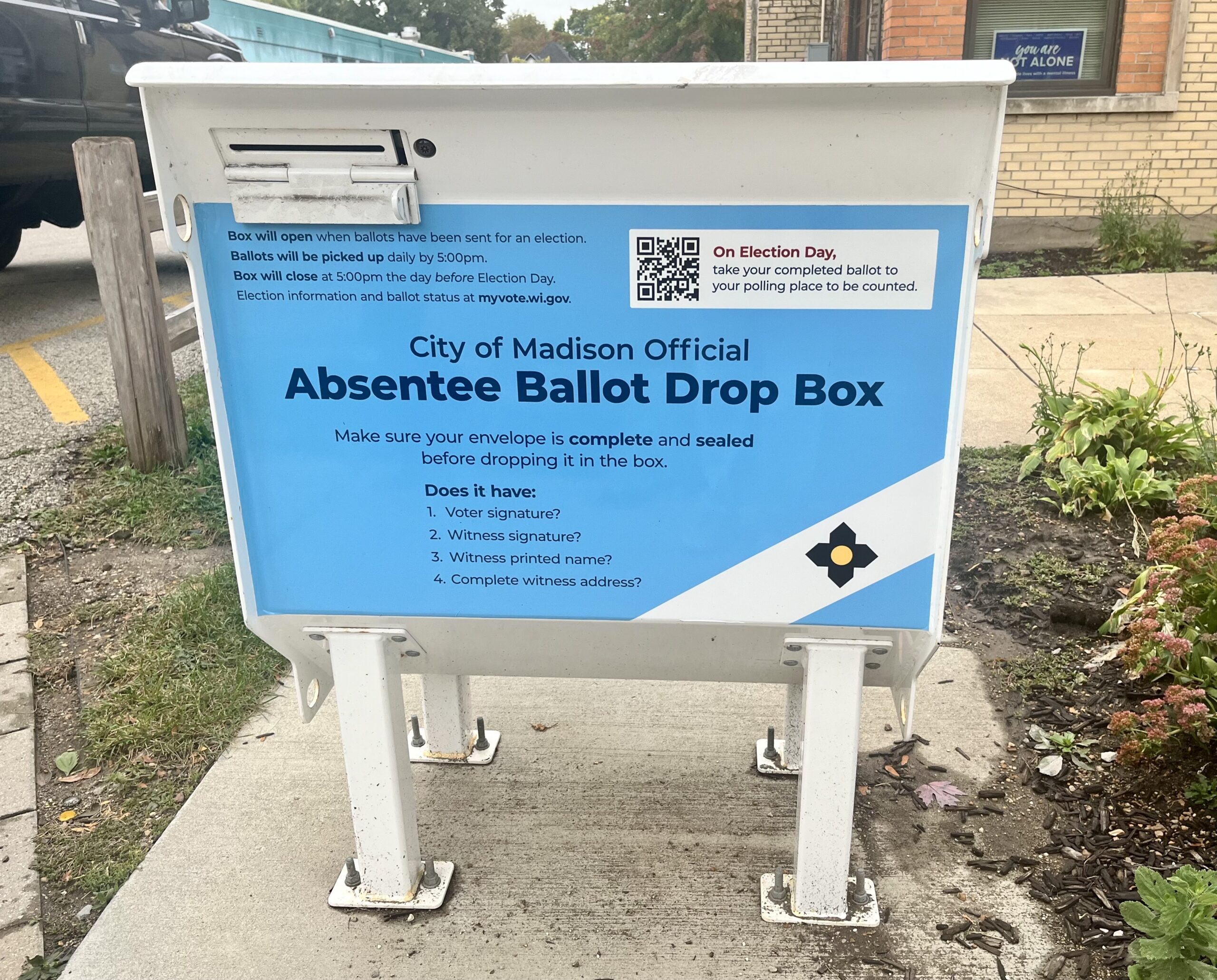

In 2010, Dane County voters weighed in against the possibility of a sales tax to fund a commuter rail line. More recently, some Republican counties asked voters to weigh in on outside grant funding for election activities, an aspect of the 2020 election that Wisconsin Republicans have widely criticized.

But when the provision against these referendums appeared in the GOP revenue-sharing proposal, it was Democrats who came out against it.

At Thursday’s committee hearing, Milwaukee County Supervisor Peter Burgelis said his county has held “a number of (referendums): one on sex, one on drugs and another one on guns.”

He said they help leaders hear how public opinion changes over time. If that process went away, data collection would become more onerous. Moving to an alternative like online polling would also be less reflective of a diverse community like Milwaukee, he argued.

“There’s a very clear distinction of the racial makeup of people who respond to an online survey, as compared to other methods can gauge their opinion,” he said. “And the diversity of people who can interact online with their county government is far different than the racial makeup of the county residents and voters.”

Rep. Clinton Anderson, D-Beloit, compared local advisory referendums to one put on the April ballot by Republicans regarding job seeking requirements for people receiving public benefits.

“Do you think it’s a little weird that you’re pushing a ban on advisory referenda at the local level, but, yet, the Legislature pushed a statewide advisory referendum in the April election?” he asked.

“I don’t see any problem with that,” Rep. Tony Kurtz, R-Wonewoc, replied.

In 2019, when Racine County officials declined to put a referendum about legislative maps on their ballot, county supervisor Tom Roanhouse said it “circumvents and undermines democracy.”

Vos told reporters he supports local advisory referendums for issues of local concern, but not state issues that local lawmakers have no control over. Getting rid of them altogether was a compromise, he added.

“We just said, it’s easier to have none of them, so don’t get into slicing and dicing what they are,” he said.

Some critics also argue local advisory referendums are used more as a tool for driving up turnout in an election than to promote actual policy change.

Barry Burden, a political scientist and elections researcher at UW-Madison, said their effect on voter turnout is “probably highly variable from one election to another.” But in some cases, he added, even a small boost from a ballot initiative could sway the outcome.

“It is possible that a referendum on a hot-button issue could juice turnout somewhat in an election that is otherwise not especially engaging,” he told Wisconsin Public Radio in an email. “An important condition is that potential voters are made aware that the issue is on the ballot and it is compelling enough to encourage their participation.”

For advocates like Storck, who has used local referendums to push for statewide change, the potential loss of this tool feels personal.

“It’s kind of a hopeless feeling for me that, really, without these referendums available to demonstrate that the public is behind it, that there’s very little citizens can do,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.