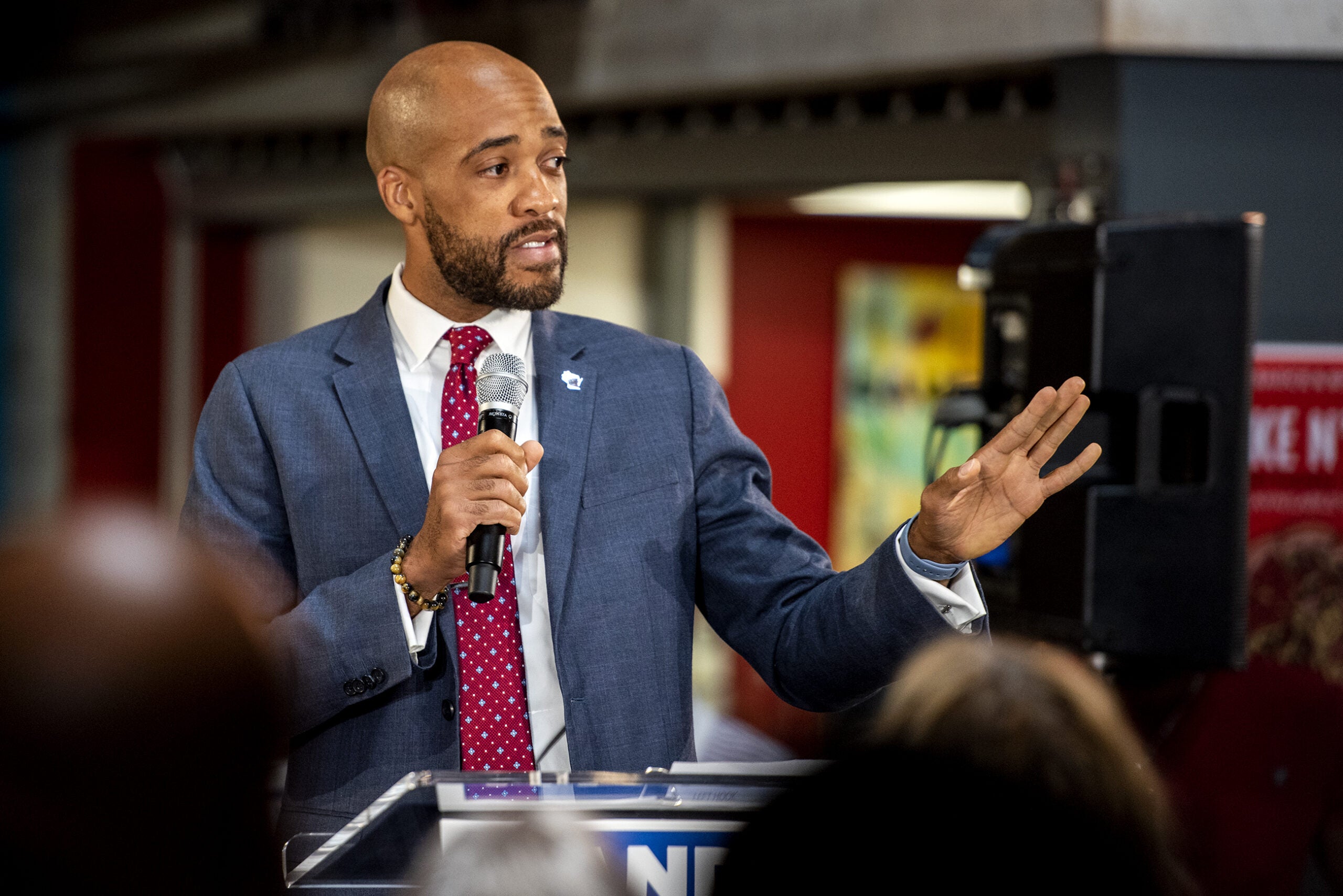

For more than a year, Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Mandela Barnes emphasized his middle-class roots to run a progressive campaign he hoped would carry him through the Democratic primary. Last month, as one Democrat after another left the primary to endorse him, it suddenly paid off.

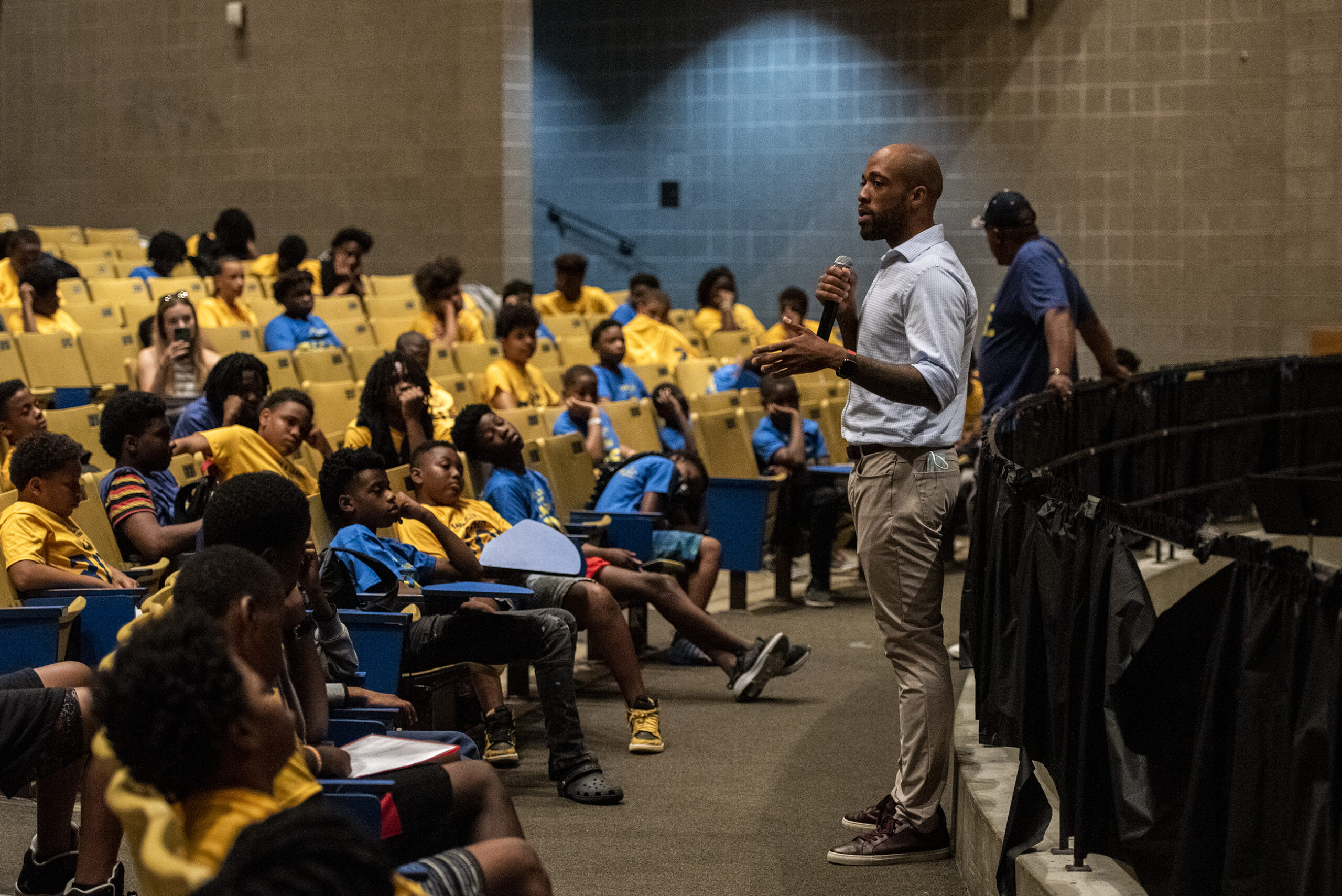

Barnes describes his journey from Milwaukee kid to State Assembly to being Wisconsin’s first Black lieutenant governor and now Democratic front-runner in one of the nation’s most hotly contested Senate races as “a very Wisconsin story.”

“I come from a working class household,” said Barnes in an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio. “My mother was a public school teacher for 30 years. My dad worked on an assembly line third shift for 30 years.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Over the past year, Barnes has consistently used his childhood to add personal flair to policies supported by Democrats in the race.

He points to his father’s career building catalytic converters in Oak Creek after the Clean Air Act of 1970 was passed as an example of how a congressionally-mandated transition to renewable energy could spur solar panel and wind turbine manufacturing in Wisconsin.

Three weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Barnes shared the story of the time his mother got an abortion.

“Her health was at risk,” said Barnes. “She had to make the decision to end that pregnancy. But it was her decision to make. And that’s a decision that any woman across this country should be able to make without interference from politicians.”

Personal stories aren’t unexpected in politics, but Barnes has put repeated emphasis on his working-class roots as he fought a primary battle that — until recently — included millionaires like State Treasurer Sarah Godlewski, who has loaned her campaign nearly $3.6 million and Milwaukee Bucks Executive Alex Lasry, who poured $12.3 million into his Senate run.

Now, Barnes will be running against another millionaire, Republican U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson.

Barnes has also emphasized his progressive views, which have served him well in the primary but are already being scrutinized by Republicans ahead of the general election.

“We have long known that Barnes is well-liked among the Democratic Party base,” said University of Wisconsin-La Crosse political scientist Anthony Chergosky. “But can he connect with the swing voters who decide close elections here in Wisconsin?”

‘An Unlikely Candidate’

In 2004, Barnes said he got the itch for politics while watching then-Illinois Sen. Barack Obama give the keynote speech at the Democratic National Convention in Boston. Obama delivered the speech roughly four years before he would become the nation’s first Black president.

“He talked about being an unlikely candidate,” said Barnes, who would be Wisconsin’s first Black U.S. Senator if he were to win in November. “He talked about a person that probably, under most circumstances, wouldn’t have been able to get on that stage. But he also made it very clear that his story was only possible in the United States of America.”

After leaving college in 2008, Barnes was an organizer with Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope, or MICAH, and a member of groups including the ACLU and NAACP. He also served on the staff of former Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett.

United Auto Workers Local 72 Vice President John Drew said he met Barnes in 2011 at Wisconsin’s Capitol amid a sea of people protesting former Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s push to restrict public employee union bargaining rights.

“I distinctly remember Mandela coming up to me and looking me in the eye, sticking his hand out and saying, ‘I’m Mandela Barnes, and I’m an organizer,’” said Drew. “And it took me a little while to put the pieces together, but then I realized that Mandela’s dad was Jesse Barnes, who was one of our active UAW members and retirees. And it all kind of fit.”

Drew said he’s known Barnes ever since and has watched him grow as a political leader. On policy, Drew noted there weren’t a lot of significant differences between Barnes and other Democrats in the race.

“It’s just, you know, there’s a lot of millionaires in the Senate, OK?” said Drew. “There’s not too many Mandela Barneses in the Senate.”

Barnes has shown an ambitious streak since he entered politics. He won his first campaign in 2012, defeating state Rep. Jason Fields, D-Milwaukee, in a primary challenge. Barnes won the race by running to the left of Fields, including by attacking him for not signing the recall petition against Walker.

“Had I been in the Legislature, I would have certainly signed a recall petition,” Barnes told WisconsinEye in 2012. “Yes, it is an issue.”

Barnes mounted another primary challenge in 2016 but lost by a wide margin to Democratic State Sen. Lena Taylor of Milwaukee.

It didn’t deter him. Barnes was back at it in 2018, winning a primary for lieutenant governor and joining the top of the ticket beside Tony Evers, then the Democratic nominee for governor. The duo went on to defeat Walker and former Lt. Gov. Rebecca Kleefisch, calling it a new day for state politics.

“We are bringing education back to the state of Wisconsin, we are bringing science back to the state of Wisconsin, and we are going to bring equality back to the state of Wisconsin,” said a triumphant Barnes on election night. “It does not matter what zip code you come from or your family’s income. Our mission is to make sure that Wisconsin is a state that once again provides opportunity to everyone.”

State Rep. Francesca Hong, D-Madison, said she met Barnes at a Planned Parenthood event in 2020, the year she won her first election to the state Assembly.

Hong said they connected on issues like climate change and her office relied on Democratic Governor Tony Evers’ Task Force on Climate Change, which Barnes chaired, when setting its own climate policy. Hong said the Lt. Gov. also advised her on organizing efforts outside of her ultra-blue Madison district.

“You feel like you have an ally and sharing your platform and connecting with folks who don’t always have an entryway to politics,” said Hong. “Him being really open to that helped me as a freshman legislator feel like, ‘Okay, I can keep pushing.’”

With the primary largely behind him, a challenging road ahead

Just last month, polling from Marquette University Law School pointed to a close primary race between Lasry and Barnes, with Godlewski and Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson farther behind.

But over the course of five days in late July, all of Barnes’ closest competitors dropped out of the race and endorsed his campaign.

“To have every single major candidate drop out just weeks before Election Day, when these candidates have put in hard work, they’ve spent money — some of it their own money — to give way to the front-runner and now presumptive nominee, Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes … it really is unprecedented,” said Cook Political Report Senate and Governors editor Jessica Taylor.

If Barnes is looking for a progressive’s guide to winning one of the nation’s most purple states, Taylor said, he should look to Democratic U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, who won reelection in 2018 by boosting turnout in Milwaukee and Madison while not getting clobbered in rural Wisconsin. Baldwin won her race by 11 percentage points.

“And so that’s where I could think that he could do some work and maybe a populist message could appeal there,” Taylor said.

Throughout the primary race, Barnes racked up a long list of big-name endorsements from left-leaning progressives in Congress. Last September, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, went all in for the lieutenant governor, calling him a “tireless advocate for people all across Wisconsin.” Then came nods from Congressman Jim Clyburn, D-South Carolina, Congresswomen Alexia Ocasio-Cortez, D-New York, and Gwen Moore, D-Wisconsin, with the last and biggest endorsement coming from U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, the self-described democratic socialist from Vermont.

The endorsements added weight to Barnes’ progressive bona fides and helped launch him past fellow Democrats. But already, Johnson and national conservative groups are using them as part of a larger strategy to paint Barnes as an out-of-touch, radical liberal.

“Barnes has been the one that Republicans most wanted to run against,” said Taylor.

Almost immediately after the Democratic field had cleared, the conservative Senate Leadership Fund issued a statement filled with screenshots of his tweets dating back to 2017 mentioning “the ills of capitalism,” his support of Medicare for all and the Green New Deal. It also included a picture of Barnes holding a shirt calling for U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement, known as ICE, to be abolished — a position from which Barnes has since distanced himself.

The Senate Leadership Fund statement contained a warning for Democrats about choosing Barnes to go up against Johnson in November.

“They’ll come to regret it,” said the statement.

Barnes will likely continue leaning on his middle-class roots as he faces off against Johnson, who was worth between $16.6 million and $78.4 million last year according to a filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Barnes’ net worth was somewhere between $5,005 and $75,000 according to his SEC filing. His annual salary as lieutenant governor is $80,684.

“Most people in the state, most people in this country are not millionaires,” said Barnes. “They go to work, they face struggles, whether it’s paying the bills, wondering, you know, how things are going to be the next week or the next month.”

While Barnes may not have the personal wealth of Johnson, he’s been a proficient fundraiser. Barnes received more than $7 million between July 1, 2021 and July 20, 2022 according to filings with the FEC. Of that, more than $171,000 came directly from political action committees. The FEC list of Barnes’ PAC contributions includes groups like ActBlue and MoveOn.org, which gather donations from Democratic donors.

After Nelson, Lasry and Godlewski dropped out of the race, the Barnes campaign said it raised $1.1 million in just a week.

Along with passing a new Voting Rights Act and ending the Senate’s filibuster rules requiring 60 votes to pass legislation, Barnes said getting corporate and special interest money out of politics is a key tenet of his “Plan for Democracy.”

When asked about the juxtaposition of his messaging and his PAC contributions, Barnes specifies that the campaign has “not taken a dime of corporate PAC money.”

Ron Johnson has no such qualms, and he’s been a fundraising juggernaut throughout his re-election campaign. Johnson brought in more than $12 million in donations between January 1, 2021 and June 20, 2022, including corporate PAC funds.

Throughout his campaigns for the state Legislature and lieutenant governor, Barnes has never seen a barrage of negative attack ads like the ones that are coming his way in the general election, said Chergosky at the UW-La Crosse.

“The key question is how Mandela Barnes may or may not be able to withstand millions and millions of dollars of negative ads targeting him because that’s what’s coming,” said Chergosky.

But Barnes said those attacks are expected, and he’s ready for them.

“They will try to lob every sort of false attack against whoever comes out of this primary,” said Barnes. “But the way you beat that is with a strong message and with enthusiasm. This campaign has generated enthusiasm I could not have imagined.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.