Everyone knows you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but there’s a chance you could learn something by counting the pages in a state budget.

It’s not that the length of a budget says anything about whether it’s good or bad. Short budgets can spend lots of money. Long budgets can be frugal. A single sentence or dollar figure can go a long way toward setting public policy.

But fewer pages means fewer words. And fewer words means fewer chances for a Wisconsin governor like Tony Evers to reshape the budget once the Legislature sends it to his desk.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“In the case of this budget, it seems to me that if you have a short bill, then to a certain extent you’re giving the governor fewer opportunities for line-item vetoes,” said Mordecai Lee, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee professor, a former state senator and a longtime observer of Wisconsin’s budget process.

“I think we’re seeing a real behind-the-scenes strategy here by the legislative leaders knowing that they’re going to face the opportunity for a governor to reshape a budget,” Lee said. “They’re giving him as few opportunities as possible to be able to do that.”

The Wisconsin budget bill Republican lawmakers passed this week is shortest in decades, and it’s not even close.

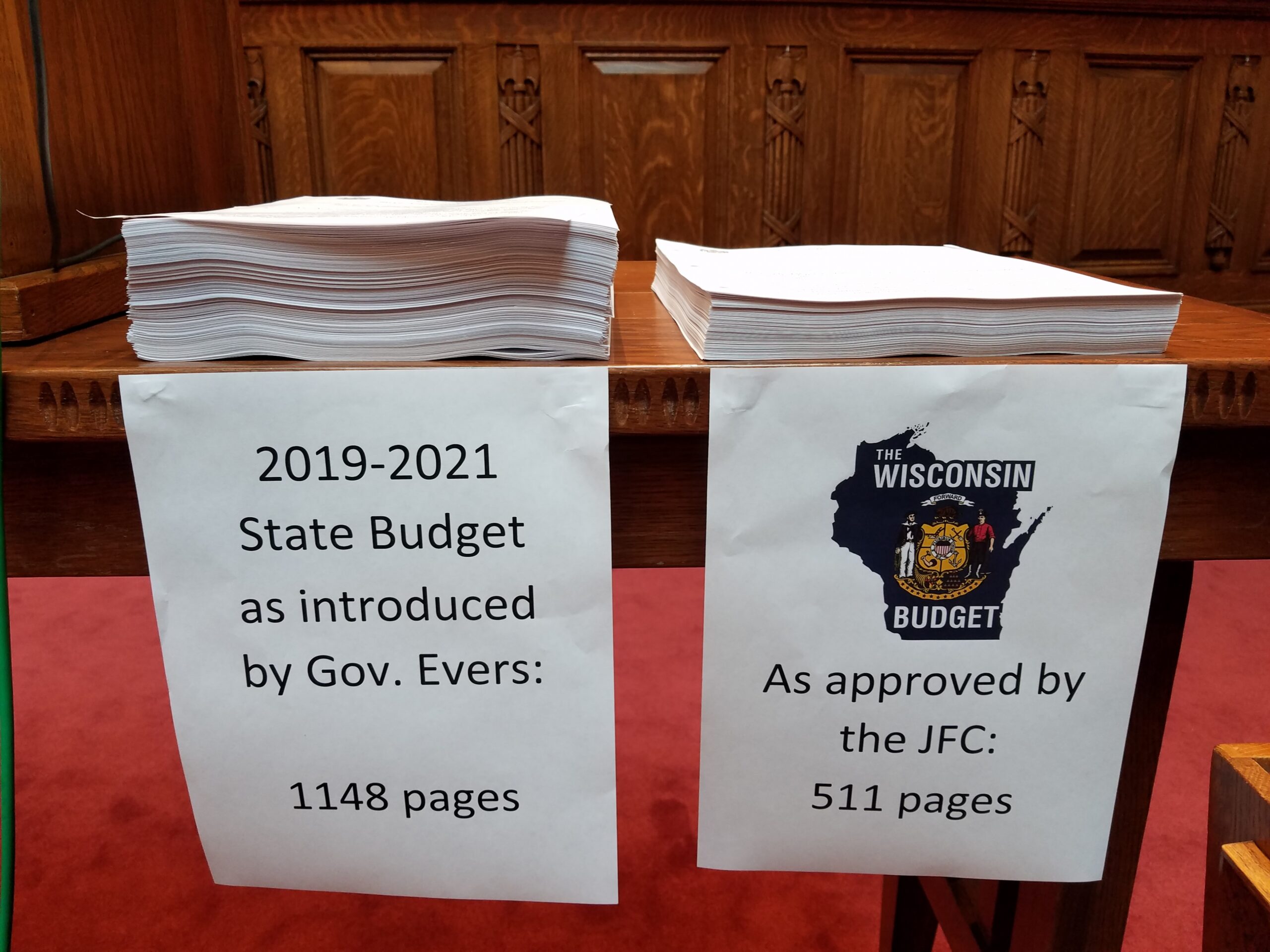

When it passed the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee, the bill was 511 pages. The budget bill introduced by Evers in February was 1,148 pages.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester called attention to the difference during a press conference before the budget vote. Next to Vos were paper copies of the governor’s budget bill the Republican alternative.

“When Gov. Evers introduced his request in February, the document was a massive liberal wishlist, more than 1,100 pages filled with policy to appease Democrats and their special interest allies,” Vos said. “For those of you who are keeping count, we cut the number from the original document by more than half.”

That’s not to say Republicans are averse to longer budgets. They’ve written several.

In fact, every budget bill passed out of the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee over the past two decades has been more than 1,000 pages.

That includes the four budgets GOP lawmakers passed when Republican Scott Walker was governor. Those budget bills averaged about 1,400 pages, or about 250 pages longer than the budget Evers introduced.

“The length of a law, the length of a bill is really irrelevant to if it’s good or bad or important or unimportant,” said Lee.

But Lee said it could matter when it comes to Evers’ ability to use his partial veto power.

“That reduces the opportunities for a governor to line-item veto some changes he doesn’t like because it’s not presented,” Lee said. “It’s not in the bill.”

While Republicans have reduced the power of the Wisconsin governor’s office in other ways, Evers’ veto power gives him broad authority to reshape appropriations bills like the budget.

In a report issued earlier this year, the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau called the Wisconsin governor’s partial veto power “unique across all states.”

“Most state constitutions grant the governor ‘item veto’ power over appropriation bills, allowing the governor to strike or reduce appropriations,” read the report. “But the partial veto power allows the governor to strike words, numbers, and punctuation in both appropriation and non-appropriation text, thus giving the governor a role in the lawmaking process in a far more substantial way than simply having veto power over an entire bill.”

Republicans are well-aware of those powers. Vos said Tuesday that they tried to make the budget as “veto-proof” as possible.

For example, they made several, subtle tweaks to the language of the budget with the governor’s veto powers in mind.

One amendment changed the phrase “not to exceed” to “up to” on a handful of occasions. Another amendment changed the phrase “may not” to “cannot.”

Democratic lawmakers called attention to the changes, with Rep. Mark Spreitzer, D-Beloit calling the amendments “petty obstructionism.”

“(Republicans) discovered that maybe they just left a tiny little bit of wiggle room for the governor to use his constitutional powers to improve this budget,” Spreitzer said. “And wouldn’t you know it they want to take away any power they can for the governor to improve this budget.”

Assembly Majority Leader Jim Steineke, R-Kaukauna, disputed that characterization.

“This amendment simply seeks to clarify the Legislature’s position to ensure that the governor cannot use his veto authority to subvert the will of the body,” Steineke said. “Period.”

Lee said it’s important to note that while Evers’ budget power is still broad, there are limits to what he can do to a budget.

“We have to remember that a line-item veto can only reduce a number,” Lee said. ” You can’t increase a number.”

So, for example, when it comes to education funding, Republicans passed a $500 million increase for K-12 schools. That’s about $900 million less than Evers wanted, but he can’t use his veto pen to put the money back.

Lee said Evers could veto the entire budget if he wants to restart negotiations and push for a better compromise, but such a move would be unprecedented in Wisconsin.

The Legislative Reference Bureau says no Wisconsin governor has ever vetoed an entire budget outright since the state moved to a biennial executive budget in 1931.

Evers’ office didn’t respond to a question about whether the length of the budget would restrict his partial veto options, and whether that concerned him.

The governor has consistently kept his options open when it comes to vetoes, saying he needs to consider the budget in its totality before making final decisions.

Evers tweeted Thursday that he had called on the Legislature to send him the budget bill, a procedural step that begins a countdown for the governor. Once the bill is sent to his desk, Evers has six days, not counting Sundays, to act on it.

If he uses his partial veto powers, 500 pages will give him plenty of room to make changes — just not as much room as his predecessors.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.