School leaders and organized labor in Wisconsin say they’re cautiously optimistic following a lower court ruling Monday that would restore collective bargaining rights for many public employees.

But they say they’re not declaring victory over Act 10 yet and say they are expecting more litigation in the fight over former Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s landmark law which severely curtailed most public sector unions.

On Tuesday, the GOP-held state legislature filed a notice of appeal over Monday’s decision out of Dane County circuit court. The case is expected to eventually make its way to the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

There, liberal judges currently hold a 4-3 majority. But the court’s ideological makeup is in flux, as one liberal justice is set to retire and an election to replace her will take place in April.

And two other justices on the high court were involved in opposite sides of the law’s passage thirteen years ago, raising questions about who, ultimately, will decide the future of Act 10.

Speaking to reporters at an elementary school in Horicon on Tuesday morning, Gov. Tony Evers called the decision an “important step forward” for union workers, but said the matter was far from decided.

“I think it’s an important win, but I also recognize that the process is long,” he said.

Supporters of Act 10 have denounced the ruling, calling it judicial activism. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, has said that changes under Act 10 — such as changes to public employee insurance programs — saved taxpayers billions of dollars.

Act 10 ruling could be a win for educators, and cost school districts

Act 10 dealt a massive blow to many unionized workers in Wisconsin by significantly curtailing the rights of most public employee unions to collectively bargain.

Peggy Wirtz-Olsen, president of the Wisconsin Education Association Council, or WEAC, said the ruling was a win for teachers, but knows challenges are coming.

“Teachers like me are celebrating yesterday’s victory, but we certainly recognize that it’s one more step forward in what we know will be more legal legwork coming,” Wirtz-Olsen said.

WEAC and other labor unions representing public employees filed a lawsuit in November 2023 challenging the constitutionality of the law.

Wirtz-Olsen said the rules imposed by Act 10 left the state’s education workforce in crisis, with 40 percent of teachers leaving the profession in the first six years because of low wages and unequal pay.

“We know that the union is the place to fight for those educators in our schools,” Wirtz-Olsen said. “Their working conditions affect our students’ learning conditions.”

Since Act 10 was enacted in 2011, participation in public sector union membership has dropped significantly.

From 1984 to 2011, between 45 percent and 60 percent of public sector employees belonged to a union, according to a Wisconsin Policy Forum report.

But by 2020, just 22 percent of the state’s public employees were union members.

Since the law was passed, Wisconsin’s public sector unions have lost about 11,500 members per year, the report found.

Teachers unions have been more successful at recertifying than other public sector unions. Under the law, employees must vote to recertify annually to keep a union in place.

“(Teacher’s unions) decided to take an aggressive posture towards continuing to organize and continuing to function as a union,” said Richard Saks, a retired labor lawyer. “A lot of unions took the position that … it was futile to make an effort in under this law to organize the workplace into a union.”

If Monday’s Act 10 ruling holds, unions representing teachers could bargain for raises beyond the cap imposed by the law and negotiate for improved healthcare and pension benefits.

Over the last 13 years, declining enrollments and stagnant state aid payments have further tightened school district budgets.

Starting in 2016, school districts have increasingly turned to taxpayers, through referendums, to increase their revenue limits.

An April report from the conservative law firm Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty estimates that restoring collective bargaining for teacher salaries could cost districts and the state nearly $650 million annually.

The report also estimates that eliminating employee contributions to retirement and health care could cost school districts and the state $422 million and $560 million annually.

“Overturning Act 10 could have a devastating effect on Wisconsin taxpayers, as well as the budgets of local school districts,” said report author Will Flanders.

Dan Rossmiller, executive director of the Wisconsin Association of School Boards, said if Frost’s decision remains in place, it provides no additional resources to school districts, but requires school districts to bargain over wages, hours and conditions of employment.

If school districts begin to incur substantial cost increases because of the restoration of collective bargaining that are not offset by more state aid, the likely result will be fewer educators and fewer educational programs for students, Rossmiller said.

“Those educators a district cannot support given its finances would likely be laid off,” Rossmiller said.

Union leader sees opportunity in Act 10 court decision

Union leaders’ cautious optimism is a stark contrast from their stance 13 years ago, when the law was enacted. National media descended as protesters engulfed the state Capitol in Madison for weeks.

Peter Rickman was a student leader at those protests then. Now, he’s president of the Milwaukee Area Service and Hospitality Workers Organization. He said rebuilding public sector unions in the absence of Act 10 will be difficult.

“The fundamental challenge for Wisconsin labor, for public employee unions and beyond, is to rediscover the muscle memory that it takes to organize workers,” he said. “There’s not a lot of muscle memory. It’s been a generation of public sector trade unionism here that’s been decimated.”

But he argued the rebuilding process could present an opportunity for organized labor, too.

While Rickman represents workers in private industry jobs — whose rights were not affected by the Act 10 decision — he argued that restoring practices like collective bargaining for the public sector improves working conditions, which translates to improved services for average people.

“Here, we can actually capture little bit more power for working people and shape public institutions for the common good,” he said.

With state Supreme Court makeup in flux, Act 10’s future is uncertain

Act 10 was one issue raised during the high-profile and expensive race for an open seat on the state Supreme Court. That election ultimately flipped the ideological balance of the court to a liberal majority.

The question of overturning Act 10 came up on the campaign trail, because Justice Janet Protasiewicz — who ultimately won the open seat — had participated in the protests against the law. Protasiewicz has not said whether she will recuse herself if the case comes before the court.

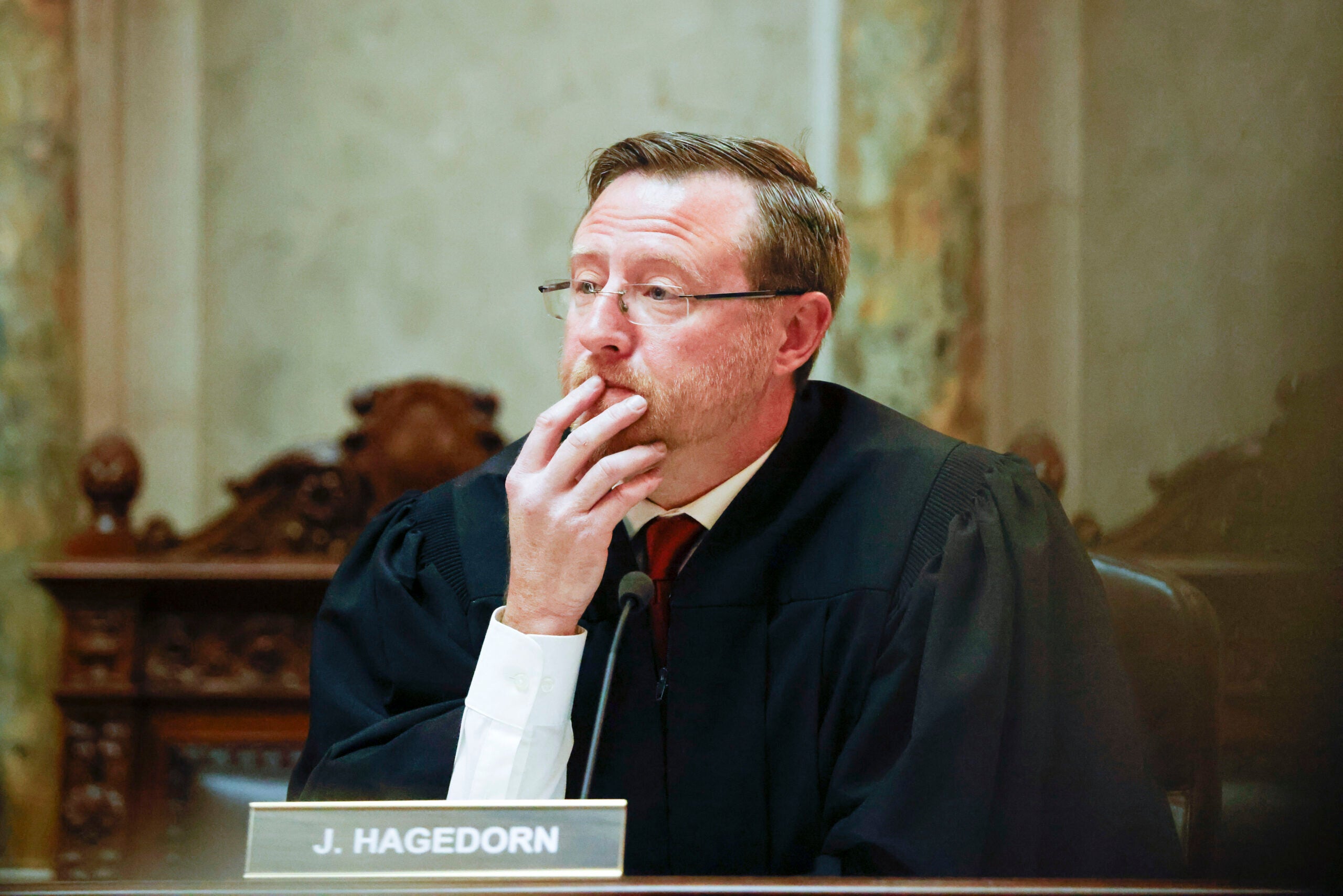

Meanwhile, conservative Justice Brian Hagedorn served as Walker’s chief legal counsel at the time the law passed and was involved in its drafting. In his own campaign for the high court, he also did not say that he would recuse himself.

And an April election will once again decide whether Wisconsin’s Supreme Court is majority conservative or liberal. Liberal Dane County judge Susan Crawford and conservative Waukesha County Judge Brad Schimel are both in the running to replace retiring Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, a liberal who announced earlier this year that she will not run for reelection when her term expires next summer.

Depending on how the challenge to the Act 10 case proceeds, the case could end up in front of the current court — or be part of the rationale behind another high-cost and highly polarized court race.

Walker indicated as much in his reaction message about Monday’s decision, when he encouraged pro-Act 10 voters to get involved in that election.

“So speak out. Get ready for this spring,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.