The Wisconsin Elections Commissions hasn’t seen any evidence or received any formal complaints suggesting Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg had undue influence in Green Bay’s November 2020 election, according to the commission’s administrator.

State Republicans, including some lawmakers, have repeatedly raised concerns about grant money that Green Bay and other Wisconsin cities received from a group funded by Zuckerberg to help administer elections.

But testifying Wednesday before the state Assembly’s election committee, WEC Administrator Meagan Wolfe said nothing in Wisconsin law prohibits municipalities from using grant money to finance elections. In fact, the issue was litigated twice last year, and the right was upheld, she noted.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The money was a topic of discussion Wednesday as the committee continued its investigation into allegations that a contractor hired by the city of Green Bay was making elections decisions that should have fallen to the city clerk. During her testimony, Wolfe suggested the committee refer many of its questions to Green Bay officials. Committee Chair Rep. Janel Brandtjen, R-Menomonee Falls, said Green Bay Mayor Eric Genrich was invited to attend Wednesday’s hearing but was unable.

About 200 Wisconsin municipalities received grant money last year from the Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL), an organization funded by Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan. Milwaukee, Madison, Green Bay, Kenosha and Racine shared more than $6 million in CTCL funds.

WEC received two complaints from Brown County Clerk Sandy Juno about the grant money and the hiring of private consultants. Juno’s concerns were taken seriously, Wolfe said.

During presidential elections, it’s not uncommon for clerks to seek extra help from other departments or outside workers, Wolfe said. She personally followed up with Juno to ask for any evidence of wrongdoing and to clarify the role outside consultants should play, she said.

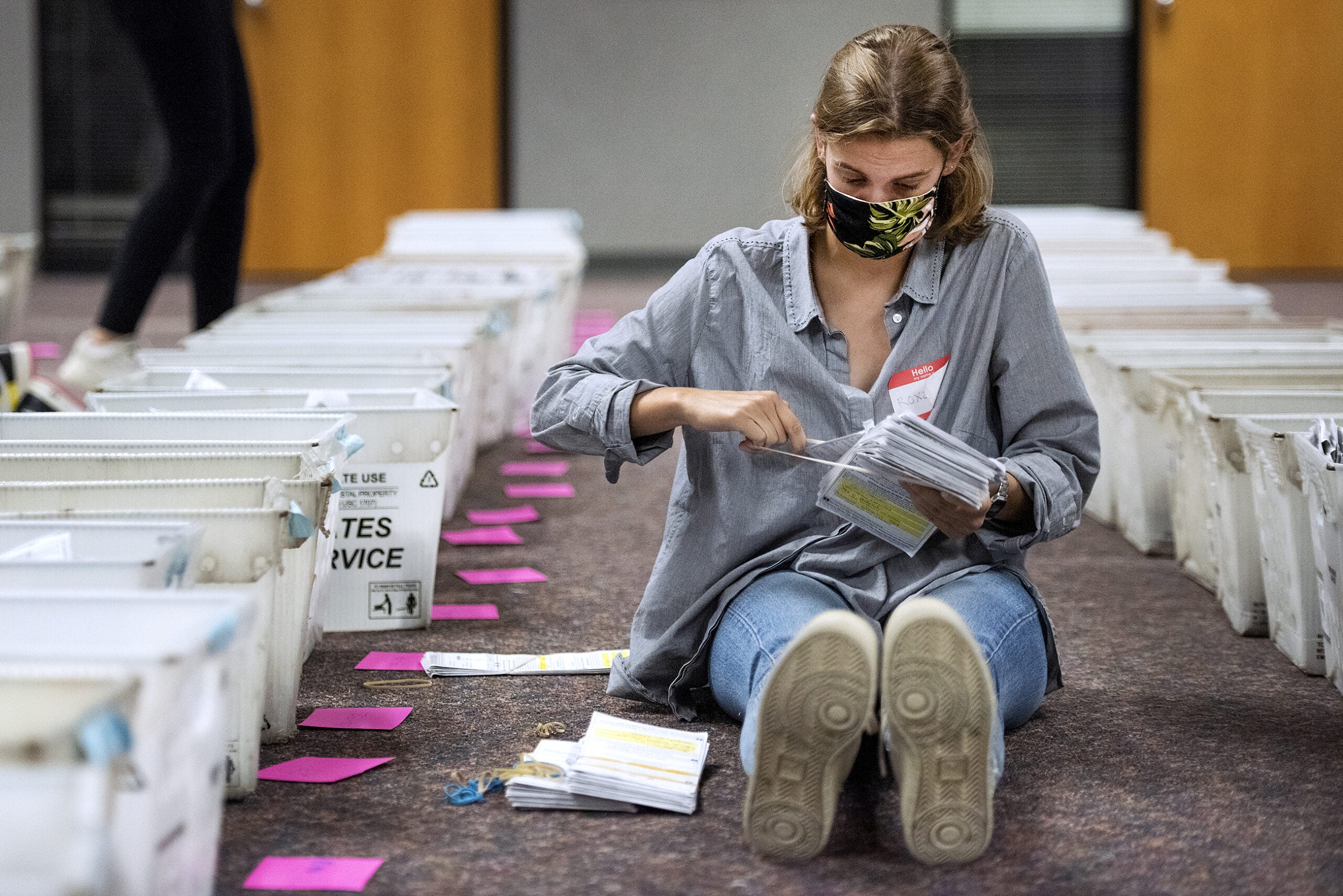

On Election Day, Green Bay City Clerk Kris Teske was on leave, so Wolfe contacted the deputy clerk to follow up on Juno’s concerns about an outside consultant at the central site where the city’s absentee ballots were tabulated.

Wolfe learned the consultant in question, Michael Spitzer-Rubenstein, was no longer at the central count location, she said. Spitzer-Rubenstein is a staff from the nonprofit National Vote at Home Institute who formerly worked on Democratic campaigns in New York.

“At no time during my conversations with the county or the municipality was I presented with information that a consultant had overstepped the clerk’s authority, or that they were handling or correcting ballots or ballot certificates,” Wolf said.

WEC didn’t encourage Wisconsin municipalities to apply for CTCL grants, nor does the commission have any jurisdiction over how municipalities spend grant money intended for elections, Wolfe said.

She did forward an email to officials in Madison, Green Bay, Racine and Kenosha in which the National Vote at Home Institute offered its services. Those communities were selected because large jurisdictions have different considerations than smaller ones, she said.

It’s not uncommon for WEC staff to be solicited by election service providers, including consultants, Wolfe said. WEC doesn’t vet those service providers before sharing their information with clerks, and clerks are required to ensure any staff they hire meets local regulations, she said.

Wolfe couldn’t speak to the exact role Spitzer-Rubenstein played on Election Day, including whether he was hired as clerk staff, she said. Typically, an election observer wouldn’t be allowed to have a laptop and phone at central count, she said. Spitzer-Rubenstein had both, Brandtjen said.

With a statewide election set for next week, Brandtjen thanked Wolfe for taking the time to discuss the roles outside entities can play in Wisconsin elections.

“We constitutionally need to create some sort of oversight process so that our voters — that you spent all this time building — feel safe, feel that we have a practical, fair, transparent election process,” she said.

Committee members also expressed concern that the city and county clerks were being bypassed when it came to making decisions about the November election. Both Juno and Teske have since left their positions, and earlier this month, Juno testified before the committee, saying that the mayor’s office was playing too big of a role in preparing for the election. A formal complaint on this topic might fall under WEC’s purview, Wolfe said.

Some Republicans, including state Sen. Eric Wimberger, R-Green Bay, have called on Genrich to resign. Meanwhile, Wolfe said there’s no evidence of election tampering, a statement echoed by Democrats.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.