Both candidates in the race for Green Bay mayor say they’ve received threatening messages directed toward their families just weeks before the April 4 election.

This comes as threats to local officials have become a growing concern in Wisconsin and across the nation — and they aren’t the first to be directed at local officials in the Green Bay area.

Wisconsin had the fourth most instances of threats or harassment toward election officials or poll workers in the country from January 2020 through September 2022, according to research from Princeton University and the Anti-Defamation League. The Badger State accounted for about 10 percent of all incidents of threats and harassment to election officials or poll workers.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

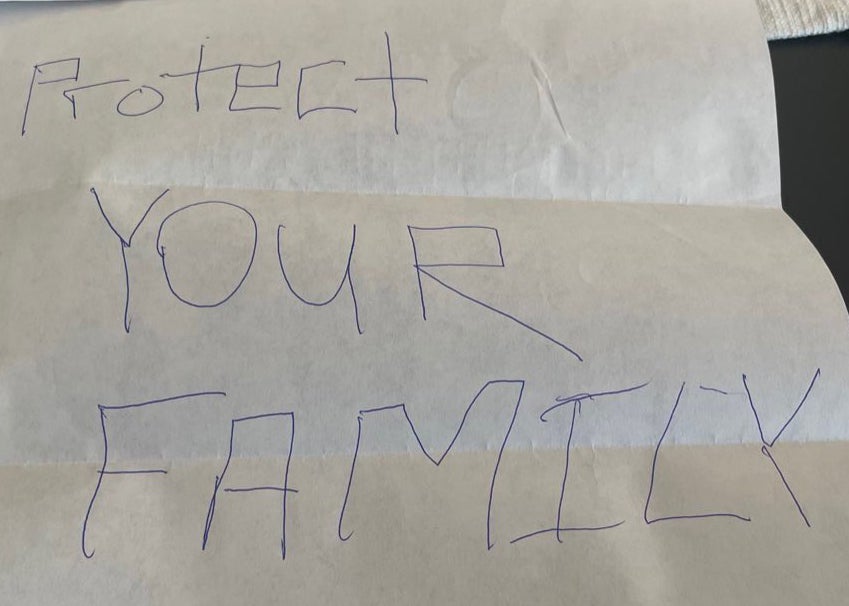

On Thursday, Green Bay Mayor Eric Genrich tweeted a photo of a letter he received that said, “PROTECT YOUR FAMILY.”

Genrich told Wisconsin Public Radio that he saw the letter yesterday, and gave it to police as evidence.

“Some people say, ‘Well, you signed up for it, being in the public light.’ But I don’t think anybody ever signs up for this kind of thing, and nobody’s family ever does,” Genrich said.

Later that day, his opponent, Brown County Administration Director Chad Weininger, released a text he received on March 17 that said, “I’ll find your family and kill them all.”

“There is no place in political discourse that should include threats of any kind,” Weininger said in a news release accompanying the text.

The Green Bay Police Department confirmed it’s investigating the letter sent to Genrich, but doesn’t have a record of a police report being filed in Weininger’s case.

“Threats against elected officials or candidates for office are serious matters and will not be tolerated,” Green Bay Police Chief Chris Davis said in a statement. “We will investigate any such attempt to intimidate our community leaders and make every effort to hold the people responsible for them accountable.”

Weininger did not respond to WPR’s request for comment. But he told WLUK-TV that he didn’t report the threat to police because he didn’t feel it reached a level where he should.

“If it would have escalated or there would have been follow-up texts provoking or if there would have been anything happening at the house, I definitely would have called,” Weininger told the station.

Genrich said threats to both candidates are not an accurate reflection of the community.

“Irrespective of political differences, we’ve got a strong, cohesive and supportive city here, and I don’t think anybody tolerates this kind of behavior,” he said.

Harassment of Green Bay officials dates back to 2020

More than a dozen officials in the city of Green Bay received threats in the summer of 2020 after the Common Council passed a mask ordinance that required face coverings in indoor public spaces.

Regardless of how council members voted, each alder received death threats, then-Alder Barbara Dorff told WPR at the time. Genrich, along with the former police chief and former city attorney, also received threats.

Harassment of local officials in Green Bay didn’t stop there. After the city became a target for Michael Gableman’s partisan investigation into the 2020 election, negative messages continued to pour in.

“We received a lot of emails and communications suggesting treason and all kinds of things because of the election conspiracy theories that have been circulated for a very long time,” Genrich said. “Our election officials, my office, other folks in city hall and in local government around the state and country have been dealing with this kind of stuff for a long time.”

The results of Wisconsin’s 2020 election, which helped President Joe Biden claim the White House, have been the subject of audits, reviews and court filings that found no more fraud than is typical in any other election. And a 168-page audit of the 2020 election by the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Audit Bureau found no widespread voter fraud.

Green Bay has gone public with three other threatening incidents in recent court filings.

In the first situation, three people “verbally assaulted” a city staff member in the Common Council chambers after a June 2021 council meeting, court documents said.

The second incident, in November 2021, involved a reporter for the Green Bay Press-Gazette being “isolated, threatened and verbally assaulted by members of the public” in a hallway after a council meeting, according to court papers.

“This harassment, with the intention of bullying a member of the press to stop doing her work as a journalist, threatens a key element of the democratic process,” the paper’s then-editor Mark Treinen wrote to city officials after the incident.

In the third incident, an election observer “verbally assaulted” staff in the City Clerk’s office after a voter delivered absentee ballots in the April 2022 election, which resulted in the voter crying and being escorted to her vehicle, court documents said.

“That interrogation ended up getting personal with this voter,” Green Bay City Clerk Celestine Jeffreys told WPR. “Myself and the entire staff, we were shaken the entire day … it was that disruptive, angry, chaotic and accusatory.”

Since becoming city clerk in January 2021, Jeffreys said election observers have viewed their role as “policing the election” — instead of observing the election.

“They insert themselves in conversations, they assert themselves in election processes, in ways that cause — in the voter — feelings of anxiety,” she said.

While Jeffreys feels safe coming to work, she said the same can’t be said for everyone in city hall.

“My family is concerned about me sometimes, especially really late at night,” Jeffreys said. “The staff gets concerned about themselves sometimes.”

Threats to local officials take increased concern

Ahead of the 2022 midterms, a growing number of election officials in Wisconsin felt burned out as they faced suspicion and threats, according to PBS Wisconsin.

From January 2020 to September 2022, Princeton University and the Anti-Defamation League found at least 14 incidents of threats or harassment toward Wisconsin’s local election officials and poll workers. Only Pennsylvania, Georgia and Michigan had more instances of harassment or threats to elections officials — all of which were swing states in 2020.

“Threats and harassment against local officials present a significant challenge to American democracy,” Oren Segal, vice president of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, said in a statement.

A March 2022 Brennan Center for Justice poll of 596 local election officials from around the country found that 1-in-6 local election officials experienced threats, while more than three-quarters believed threats increased in recent years.

The U.S. Department of Justice created a law enforcement task force to address the rise in threats against local officials in July 2021.

Tom Ivacko is executive director of the Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy at the University of Michigan. He said the main driver behind the harassment of local officials is former President Donald Trump’s efforts to convince people that the 2020 election was stolen and that the mainstream media is the enemy of the people.

“There’s been a very concerted, ongoing effort with very strong media behind it to convince people that there are enemies in the public sector, undercutting their own democracy and working against the interests of the people,” he said. “In my opinion, that’s probably the key factor here.”

Ivacko said threats to local officials make people less likely to work in local government or less likely to volunteer on local committees and commissions.

To combat the rise in harassment of local officials, Ivacko said there needs to be a concerted effort to teach civics and media literacy by schools, local governments, nonprofits and businesses.

“On Jan. 6, 2021, we almost lost our democracy, so there is a lot of concern, legitimately. But it’s not too late to kind of turn the tables here and start to put things back on a positive track,” he said. “But it’s going to take everybody, I think, engaging in this.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.