Brian Sammons knows every ingredient in the vodka, gin, rum and liqueur he makes from scratch at his Milwaukee distillery. And he handles almost every aspect of the business.

Almost.

Sammons, who opened Twisted Path Distillery in 2014, gets his certified organic milled grain from a farm in Dodgeville. He dumps 600 pounds of it into a tank, mixes it with water, then heats it to make what’s known as a mash.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In another set of tanks, he’ll mix the mash with yeast, where it will ferment to form alcohol.

He’ll refine the alcohol by heating it in a still, which is sort of like a 300-gallon stainless steel and copper tea kettle. One of his stills is equipped with a patented heating system that Sammons designed himself.

Depending on the spirit he’s making, Sammons will add other products for distinct flavor. For gin, he adds juniper and a mix of spices. Then, he distills it again.

Sammons bottles his own spirits and serves them in a tap room in the same building, sometimes neat, sometimes mixed with freshly squeezed juices, or sometimes infused with ingredients ranging from locally grown mints to avocado.

But under the complicated labyrinth of laws that regulate alcohol in Wisconsin, Sammons’ control over every aspect of his business ends there.

He needs someone else to distribute his spirits once they leave his building, and he could be fined, or even jailed, if he tries to do it himself.

“There’s a bar around the corner that carries my spirits,” Sammons says. “They sell drinks with my gin. If they run out of my gin on a Saturday and they call me and say ‘Can you run some gin over? We are right around the corner.’ My answer would be ‘I’m afraid that would be nine months in jail for me and I would lose my business.’”

He goes on.

“State law prohibits me from taking spirits I make, and legally sell, to the bar around the corner that legally sells my spirits. By law it has to go to a distributor, has to go to the distributor warehouse, has to be gotten off the truck, touch the ground, put back on the truck, then drive to the bar, and has to be marked up by a minimum amount by law.”

Sammons pauses for a moment and regathers.

“Why?” he asks. “That is the fundamental right there. Why?”

“State law prohibits me from taking spirits I make, and legally sell, to the bar around the corner that legally sells my spirits.”

Brian Sammons

The alcohol industry is one of the most regulated in Wisconsin, and the ban on distilleries distributing their own spirits is just one of many restrictions.

Wineries and breweries each operate under their own unique sets of rules, some of which have changed dramatically — and frequently — in just the past two decades.

The laws are rooted in a system of manufacturing, distributing and selling alcohol that has its roots in 1933, the year Prohibition was repealed under the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The idea back then was to create a system that would prevent some of the abuses that turned the public against alcohol and led to Prohibition in the first place.

In practice, the regulations are so full of gray areas and exceptions that even the state’s leading experts on Wisconsin’s alcohol statutes sometimes struggle to explain them.

The laws have also created an often adversarial relationship between different members of the alcohol industry, which manifests itself in fights over legislation at the Wisconsin state Capitol.

Underpinning many of those arguments is the question of who can legally distribute alcohol, a fight that’s grown more complicated as beer and liquor distributors have successfully lobbied for laws that protect their industry.

It’s a fight that’s gone on for decades, though the power dynamic is changing, partly because people like Sammons are starting distilleries, breweries and wineries all over the state.

A Three-Tier System, With Exceptions

Wisconsin had a choice to make in 1933, when Prohibition was repealed and the 21st Amendment gave states the power to regulate alcohol.

History suggests Wisconsin was eager to end Prohibition. Wisconsin U.S. Sen. John Blaine authored the joint resolution that led to the 21st Amendment, and Wisconsin was the second state to ratify it. Sales of beer with 3.2 percent alcohol began nationwide on April 17, 1933, and on Dec. 5, 1933, Prohibition for all forms of alcohol officially ended.

The 21st Amendment gave states the power to regulate alcohol, and most states built their systems around a study commissioned by John D. Rockefeller called “Toward Liquor Control.” Rockefeller was a teetotaler who had supported Prohibition, but also acknowledged its failure.

“Toward Liquor Control” warned of the dangers of unregulated alcohol that existed before Prohibition, arguing that the “saloon, as it existed in pre-prohibition days, was a menace to society and must never be allowed to return.”

“Toward Liquor Control” never specifically called for a “three-tier system,” but they began to develop in states like Wisconsin.

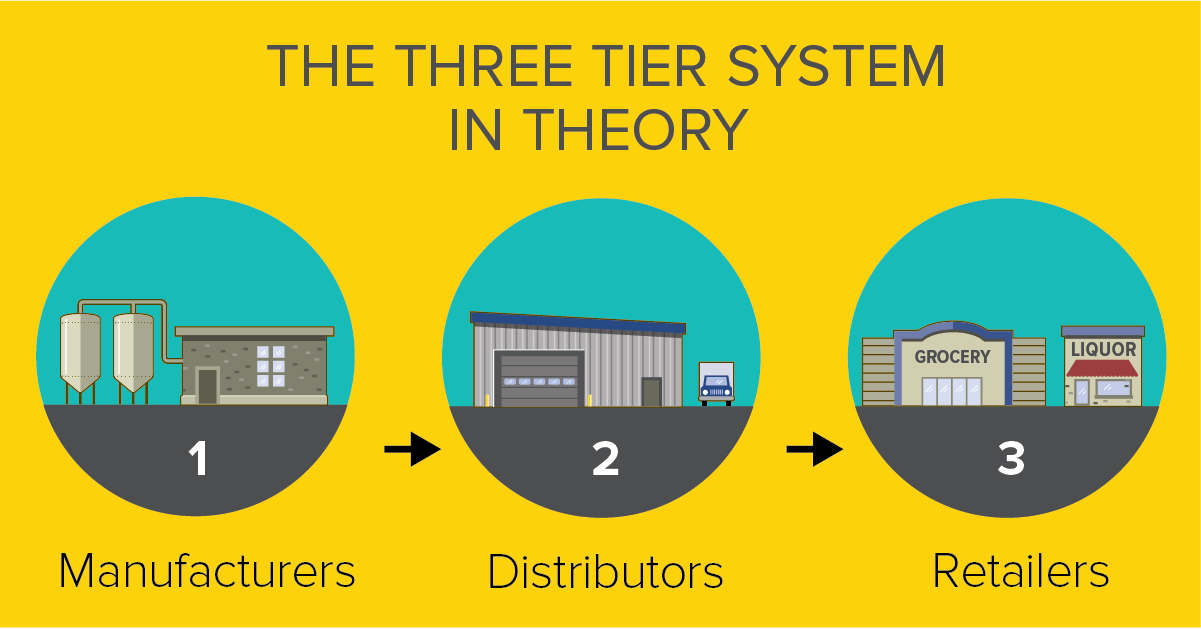

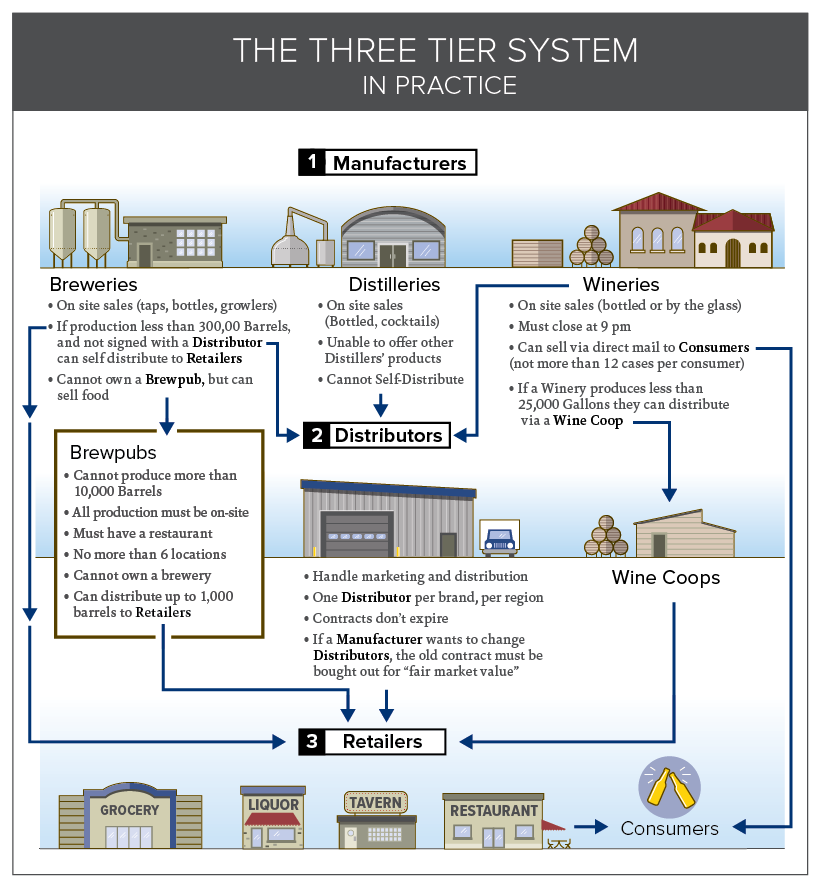

In a “pure” three-tier system, manufacturers make the alcohol, distributors deliver it, and retailers sell it to the customer. It’s that simple.

A manufacturer can be a brewery, a winery or a distillery. A distributor, also known as a wholesaler, drives the fleets of trucks that carry the beer, wine or spirits. And a retailer can be a tavern, a restaurant, a grocery store or a gas station — any place that sells alcohol to the public.

Most of the time, they’re all doing their own thing.

“The idea is that there is a vertical quarantine between the tiers — that each tier functions wholly independently” said attorney Aaron Gary at a recent symposium on alcohol laws organized by the State Bar of Wisconsin.

But Gary, who has drafted Wisconsin’s alcohol statutes for nearly two decades at the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau, is well-familiar with the myriad exceptions to Wisconsin’s alcohol laws.

“Does Wisconsin have a strict three-tier system? It does not,” Gary said.

Things get complicated really quickly. For example, a person with a brewery permit can have two retail locations where they sell beer and food, often known as tap rooms. That lets them dabble in two tiers: They’re effectively manufacturers and retailers.

Meanwhile, someone with a brewpub permit must brew beer at their restaurant. They can also serve beer, wine and liquor. To the public’s eye, an official brewpub and a brewery that serves food might be indistinguishable. But a brewpub can’t own a brewery and a brewery can’t own a brewpub.

Brewers say the ability to serve their own beer with food at their own establishment is hugely important, and their industry has undoubtedly boomed over the past decade. The state Department of Revenue, which regulates alcohol in Wisconsin, says the number of brewery permits went up from 56 in 2010 to 197 in 2018. Brewpub permits went up from 17 to 67 over that same span.

“It’s good in ways that give us an outlet to get our product to market,” said Mark Garthwaite, the executive director of the Wisconsin Craft Brewers Guild.

But Garthwaite said other recent changes took rights away from breweries in the name of preserving a strict three-tier system.

For example, since 2011, a brewery owner can no longer have an ownership stake in a licensed restaurant that serves liquor, and licensed restaurant owners can’t invest in breweries.

And breweries can no longer hold distributor licenses, known officially as wholesaler licenses, making them more dependent on Wisconsin’s big distributors to deliver their beer.

“Our ability to lift our boats together was compromised when we lost the ability to hold those wholesalers licenses,” Garthwaite said.

Despite Obscurity, Distributors Hold Sway In Wisconsin

It’s impossible to understand how alcohol laws have evolved in Wisconsin without understanding the businesses who deliver beer, wine and spirits.

That starts in warehouses like the one in Middleton run by Frank Beer Distributors, where on a recent Monday morning, Mike Frank had about 500,000 cases of beer on his warehouse floor.

Frank Beer will distribute about 5.5 million cases of beer out of this warehouse in 2019, driven in large part by national brands like MillerCoors and Corona, but also by Wisconsin breweries like New Glarus, the maker of Spotted Cow.

Frank-owned distributors in Onalaska and Sussex will distribute another 11 million cases of beer this year for a grand total of 16.5 million cases across all three locations.

Based on Mike Frank’s estimates, that means about one in every four cases of beer sold in Wisconsin gets to where it’s going on one of his family’s delivery trucks. They also own Frank Liquor, which distributes wine and spirits across a 19-county region in southwest Wisconsin.

“But most people don’t know who we are,” Frank said.

Part of that is by design. If you see a beer truck wrapped in a Miller Lite logo delivering to a retailer in Madison, Frank Beer Distributors owns the truck. The same goes for trucks painted to advertise New Glarus or any of their other brands in the territories where they distribute.

The Frank family started distributing in 1933, but took a break from distributing beer in the 1960s and 70s to focus on its liquor business.

Mike Frank’s father, Steve Frank, got Frank Beer off the ground again in 1979.

“To this day, I can remember being little, and I can remember what we had to do to be successful,” said Steve Frank. “And those things aren’t any different being big now.”

But the landscape for distributors today is dramatically different then it was when Frank started, partly due to consolidation in the wholesale industry. Against that backdrop of market forces, the powerful distributor lobby has also supported a steady drumbeat of changes to state laws to protect their industry.

Consider some of the bigger changes passed in just the past two decades:

- In 1999, the state budget signed by former Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson gave liquor distributors special protections under Wisconsin’s Fair Dealership Law. This made it difficult for larger distilled spirits manufacturers to fire a liquor distributor without cause.

- In 2003, former Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle signed what’s known as the “Brand Compensation” law that that made it harder for breweries of any size to fire a beer distributor. The law was pushed by beer wholesalers and Miller Brewing.

- In 2006, Doyle signed a law that mandated exclusive territories for distributors. With exclusive territories, alcohol manufacturers can only distribute their product with a single distributor in a given region. The law also wrote a full-throated defense of the three-tier system into Wisconsin’s alcohol statutes.

- A 2008 law also signed by Doyle took away the ability for wineries to self-distribute their wine, making them more dependent on distributors. The law also explicitly banned distillers from self-distributing.

- The 2011 budget signed by former Republican Gov. Scott Walker took away the ability for brewers to hold wholesaler licenses. They could still self-distribute their beer, but they couldn’t distribute other peoples’ beer. Beer distributors and MillerCoors said the change was aimed at preventing Anheuser-Busch’s new parent company InBev from buying up Wisconsin distributors and crowding out the rest of the market.

In the real world, those changes have had tangible consequences.

Granting exclusive territories means that when a brewery signs a contract with a distributor in a given region, that distributor is the only one who can deliver the brewery’s beers. So every MillerCoors beer purchased at any tavern, restaurant or convenience store in a 23-county region covering the La Crosse, Madison and Milwaukee markets made a stop at a Frank Beverage Group warehouse, and rolled off one of their trucks.

“It is, in fact, monopolistic. And I don’t think there’s any doubt on the economics of monopolies. Monopolies raise prices, period.”

Attorney Jeffrey Glazer

Attorney Jeffrey Glazer, who specializes in Wisconsin alcohol law and represents craft breweries, argues the requirement for “exclusive territories” gives distributors a monopoly.

“I mean there’s sort of no two ways around that,” Glazer said. “It is, in fact, monopolistic. And I don’t think there’s any doubt on the economics of monopolies. Monopolies raise prices, period.”

In the past, smaller brewers could have contracted with multiple distributors to deliver their beer. Now, they can only pick one, or they can distribute their beer themselves. They can’t do both in the same territory.

If a brewer isn’t happy and decides they chose the wrong distributor, the “Brand Compensation” law means they have to buy their way out of the relationship. It requires another distributor to pay “fair market value” to the current distributor.

“Fair market value” is not spelled out in law, but Glazer said that in practice, it’s three to seven times a brewery’s gross revenue in a market.

“So if I’m selling $100,000 worth of product in the Madison market and a wholesaler wants to take over my distribution rights – ‘Wholesaler B’ wants to take over distribution from ‘Wholesaler A’ – they have to pay $300,000 to Wholesaler A, and I as a brewery get none of that,” Glazer said. “That kind of sucks.”

If the two sides can’t agree on “fair market value,” their dispute goes to arbitration, and if they still can’t agree, they can sue.

That’s what happened to Octopi Brewing in Waunakee.

Owner Isaac Showaki said he expects to brew 60,000 barrels of beer this year. He’s already one of the largest craft breweries in Wisconsin, and after he expands his warehouse and adds 20 new stainless steel tanks, he hopes to top 100,000 barrels next year.

Showaki is a contract brewer, which means he mostly brews beer for other breweries who can’t produce on his scale. His clients include national supermarket chains that he’s not allowed to name, but when a company like Trader Joe’s puts out a beer brewed in Waunakee, there’s a good chance it came from Octopi.

Octopi also brews its own beer, and in 2016, it signed a wholesaler agreement with River City Distributing, a Watertown company that also distributed Anheuser-Busch.

Months later, River City was purchased by another Anheuser-Busch distributor, Wisconsin Distributors. The sale meant Wisconsin Distributors’ portfolio of craft beer was about to grow dramatically, and Showaki worried his beer could get lost in the crowd.

He decided he didn’t want to give his distribution rights to Wisconsin Distributors, but he didn’t want to buy them back from River City either. So, rather than give in, Showaki stopped brewing his house brand altogether. He figured he still had his contract brewing business to fall back on.

“I think 99 percent of the breweries out there wouldn’t be able to have this choice to kill their brand,” Showaki said. “That would probably kill their business.”

The distributor sued Showaki, he counter-sued, and the two ended up settling out of court.

Today, his business is thriving, he has a new house brand and new distributor that he likes, but the experience in court shaped his view of Wisconsin’s distributor laws.

“There’s nothing to push them to do a good job because if they do a terrible job with your brand and they don’t sell your brand, you can’t do anything about it.”

Octopi Brewing CEO Isaac Showaki

“There’s nothing to push them to do a good job because if they do a terrible job with your brand and they don’t sell your brand, you can’t do anything about it,” Showaki said.

Wholesalers dispute suggestions that they run a monopoly and say there’s a good reason for Wisconsin’s “Brand Compensation” law and other protections.

“Wisconsin’s three-tier system promotes healthy competition within each industry segment,” said Nathan Conrad, a spokesman for the Wisconsin Wine and Spirit Institute, a lobbying group that represents wine and liquor distributors.

“Producers compete with producers; distributors with distributors; and retailers with retailers. The restriction on financial interests and influence across industry tiers functions to keep competition within each tier on a level playing field,” Conrad said in a written statement.

The DOR, which enforces Wisconsin’s alcohol laws, relies on distributors to spot problems in the system, according to Rick Uhlig, an alcohol and tobacco enforcement field agent who has worked for the DOR for 25 years.

Uhlig told the crowd at a recent Wisconsin State Bar symposium on alcohol about a Wisconsin distiller whose product was not being properly taxed or labeled.

The DOR deemed the product was illegal and decided to seize it. The agency called the distiller’s distributor, and in a matter of three days, Uhlig said the distributor had pulled it from all retail shelves in Wisconsin.

“Because we had that independent third party who was not going to lie for this guy or cover for this guy,” Uhlig said. “He has no interest in this distiller because he can’t.”

Steve and Mike Frank say laws that protect distributors make more sense when the public gets a better understanding of what they do for breweries.

In addition to the beer logos the company paints on its trucks, Frank Beer Distributors also makes customized signs to advertise beer specials for display at retailers. All of this costs money, and Steve Frank argues Wisconsin’s “Brand Compensation” law protects that investment from a brewer who wants to change a distributor for no reason.

“There’s a value and a worth to what we are selling even if we’re not selling as much as they think we should be selling,” Steve Frank said.

The Franks contend that most of the time, brewers change distributors without conflict. Distributors will sometimes even trade brands. And when a distributor buys the rights from a brewer who built their own business by self-distributing, that brewer is in for a big pay day.

“It’s a great time to be a beer consumer based on the variety.”

Beer distributor Mike Frank

And Mike Frank said there’s a benefit to craft breweries that sign with Frank. They get to ride on the same trucks that are delivering Miller products, which exposes them to new customers.

The proof, he argues, is in the wide variety of beer available on supermarket shelves.

“It’s a great time to be a beer consumer based on the variety,” Mike Frank said.

Steve Frank, who has mostly retired, said there’s no reason to apologize for how big the family business has grown, although he’s a bit nostalgic for the old days.

“It bothers me a little bit being big because it was more fun being little and growing,” Steve Frank said. “And now when you get big, you worry about staying big.”

The Changing Politics Of Alcohol In Wisconsin

In 2011 – the last time Wisconsin lawmakers passed major changes to distributor laws – they did it in what was by then a familiar way. They added it to the state budget.

The Legislature’s powerful Joint Finance Committee was meeting on May 31, 2011 to vote on the state budget piece by piece.

That night, the co-chairs of the budget committee introduced — for the first time in public — a long list of changes to Wisconsin’s alcohol laws. Staff with the Legislature’s nonpartisan budget office read summary of the motion and Sen. Alberta Darling, R-River Hills, quickly asked for a roll call vote.

Darling was stopped momentarily by Sen. Bob Jauch, a Democrat from Poplar, who said he wanted some clarification.

“It is a little difficult when you have a nine page document that didn’t come up at any of the public hearings,” Jauch said. “But then it wouldn’t be a budget without having something to do with liquor wholesalers or beer wholesalers.”

“It is Wisconsin,” Darling responded.

This was just months after the Capitol building had erupted in protest over Gov. Walker’s Act 10 collective bargaining bill. Recall elections were on the horizon, and relationships between Republicans and Democrats were raw to say the least.

But a few minutes later, this sweeping rewrite of wholesaler laws passed on a bipartisan 14-2 vote. Breweries lost their right to hold wholesale licenses, a change small brewers are still angry about today.

Longtime alcohol regulator Roger Johnson had seen plenty of fights like these during his days at the DOR.

Johnson worked for the state from 1977 until 2014. Officially, he was an “excise tax agent,” but practically speaking, he was known in the industry as the go-to person to explain what Wisconsin’s convoluted alcohol laws actually meant, and how they’d be enforced.

“I think the thing that comes to mind is that old saying that if we can’t feather our own nest, let’s fence in the competition.”

Longtime state alcohol regulator Roger Johnson

Johnson describes the alcohol statutes as “20 pages of laws, 200 pages of exceptions.” Lawmakers added to the exceptions every session, sometimes under pressure from the alcohol lobby, sometimes at the request of a business in their district.

“I think the thing that comes to mind is that old saying that if we can’t feather our own nest, let’s fence in the competition,” Johnson said. “And that’s kind of the way it was.”

Johnson said fights over alcohol laws reminded him of the “All Star Wrestling” matches he watched as a kid, when 25 wrestlers would step into a ring and fight to the last man standing.

“We were, in my role, kind of the referee in that battle royale,” Johnson said.

Distributors have often found themselves on the winning side of Capitol battles, and they’ve been active in the political arena, too.

A Wisconsin Democracy Campaign review of donations over the past 20 years shows that distributors have donated more than $3.3 million to Wisconsin candidates. That puts them in the top 5 percent of all special interest groups the Democracy Campaign tracks.

The top recipient of distributor donations over the past two decades was former Republican Gov. Scott Walker, followed by former Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle. The legislative campaign committees for both political parties rounded out the top of the list.

“They know how to play the power game,” said Wisconsin Democracy Campaign Director Matt Rothschild. “So if Democrats are in power, they’re going to give more money to Democrats, if Republicans are in power, they’re going to give more money to Republicans. To them, it doesn’t really matter which party is in power, and whichever party is in power, they’re going to feed.”

When big deals get negotiated involving alcohol regulations in Wisconsin, the distributors aren’t alone in the room.

Another major player is the Tavern League of Wisconsin, which boasts 5,000 members throughout the state.

Rep. Rob Swearingen, R-Rhinelander, was president of the Tavern League of Wisconsin before he was elected to the Legislature in 2012. He’d been a Tavern League member since 1981, when he graduated high school and started tending bar.

“It’s grassroots,” Swearingen said. “Every one of these lawmakers has a tavern in their backyard.”

Swearingen notes that there are about 11,000 active liquor licenses in Wisconsin.

“The league represents probably half of them,” Swearingen said. “The half that do belong to the league are fairly vocal.”

Former state Rep. Terese Berceau, a Democrat from Madison, remembers going against the Tavern League when she proposed raising Wisconsin’s beer tax in 2009.

“The Tavern League is considered kind of a powerhouse, but when you look at how much money they have to donate to candidates, it’s really not all that much,” Berceau said.

Berceau said the league is powerful because its members are in legislative districts throughout Wisconsin. In rural districts, the tavern is the gathering place, not unlike a school or a church.

But Berceau said taverns also draw their strength from Wisconsin’s drinking culture.

“If you think about other states, they all may have an identity of some sort,” Berceau said. “Our identity has been beer.”

Berceau said the Tavern League and others in the alcohol lobby didn’t have to try too hard to kill her beer tax bill. It went nowhere, and Wisconsin’s beer tax remains the same today as it was in 1969.

“If you think about other states, they all may have an identity of some sort. Our identity has been beer.”

Former state Rep. Terese Berceau

It used to be that when the distributors and the Tavern League worked out a deal, it had a pretty good chance of becoming law. But when they teamed up in February of 2018 on a high-profile alcohol bill, there were signs the political landscape was changing.

Liquor distributors and the Tavern League were frustrated with the responsiveness of the DOR since Roger Johnson had retired, and wanted legislators to act.

Wisconsin Wine and Spirits Institute attorney Mike Wittenwyler said that with Johnson gone, nobody at the department was stopping out-of-state retailers from shipping directly to Wisconsin consumers, which is against the law.

Wittenwyler also told lawmakers — without naming names — that some big retailers were pressuring distributors to offer them special benefits. Again, he said state regulators were missing in action.

“It’s like having a speed limit that nobody is enforcing,” Wittenwyler testified.

The liquor distributors supported a bill that would create a so-called “liquor czar” in Wisconsin, appointed by the governor to a six-year term.

It was sponsored by Republican Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald, R-Juneau. Around that same time, the Wisconsin Wine and Spirits Institute hired Fitzgerald’s brother, former Republican Assembly Speaker Jeff Fitzgerald, as one of its lobbyists.

The bill also included a measure to let Kohler Co. manufacture and sell a chocolate brandy on its resorts. Wisconsin’s alcohol laws are littered with exceptions just like it.

But craft brewers, distillers and vintners pushed back against the bill, and killed it with the help of a newfound political ally, the Wisconsin chapter of the free market group Americans for Prosperity.

AFP Wisconsin director Eric Bott, a former legislative aide to both Scott and Jeff Fitzgerald, said he’s seen firsthand how changes to alcohol laws used to come together at the Capitol.

“Usually you had people working for the distributor tier, sometimes large producers, sometimes the Tavern League in back rooms cutting deals. Rarely at that table were craft brewers, rarely at that table were wineries,” Bott said. “And so we see our role as stepping in and righting that wrong.”

“In essence, it’s the first step towards deregulating the licensed beverage industry.”

Longtime Tavern League lobbyist Scott Stenger

AFP Wisconsin also helped stop an effort to regulate wedding barns in Wisconsin. Right now, the DOR doesn’t require wedding barns to get liquor licenses when they host events where people bring alcohol.

Another conservative group, the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, filed a lawsuit this year on behalf of wedding barn owners, and conservative media outlets like the MacIver Institute have covered the issue aggressively.

Industry observers say the wedding barn issue is far from settled, but so far, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ administration has sided with AFP Wisconsin and WILL.

“In essence, it’s the first step towards deregulating the licensed beverage industry,” said longtime Tavern League lobbyist Scott Stenger, who also lobbies for MillerCoors.

AFP Wisconsin went a step further last session, supporting a bill titled “Cheers Wisconsin” that would have doubled the number of locations a brewpub could operate and doubled the amount of beer it’s allowed to sell. It would have also created a distill pub license and let wineries stay open until 2 a.m. instead of the 9 p.m. closing time they face now.

Wisconsin craft beverage producers didn’t take a position on the bill, but the Tavern League vigorously opposed it.

“In the 26 years I’ve been working for the Tavern League, that’s the worst bill I’ve ever seen,” Stenger said in a recent interview. “The people that belong to AFP obviously have an interest — a financial interest — to blow up the system. They’re large, out-of-state interests that clearly would benefit if they didn’t have to follow these rules.”

“Free market is great, but not when it comes to beverage alcohol. We’re not talking about warm milk. We’re talking about alcohol.”

State Rep. Rob Swearingen

The bill was referred to a committee chaired by Swearingen, the former Tavern League head, where it never received a hearing. Swearingen said he agrees with AFP on most issues, but not on this one.

“Free market is great, but not when it comes to beverage alcohol,” Swearingen said. “We’re not talking about warm milk. We’re talking about alcohol.”

Brian Sammons with Twisted Path Distillery has gotten his own taste of politics, running the recently formed Wisconsin Distillers Guild and testifying at the Capitol.

He describes himself as “a lefty” on a personal level, and it’s not lost on him that he’s allies with people on the opposite end of the spectrum.

“It’s been weird because Americans for Prosperity has been in our corner and they’ve been great, and I’ve hung out with Eric Bott,” Sammons said. “And we’re 100 percent on the same page on this. And I think we both kind of recognize and respect, like, let’s just talk about that stuff.”

Tavern owners and wholesalers are still major players, but as Wisconsin’s craft industry has grown, people like Sammons say he’s seen a change in the way they’re perceived at the Capitol. Lawmakers all over Wisconsin now have breweries, distilleries and wineries in their districts, and their constituents like them.

“We started out with people pretty afraid of the power of the Tavern League and the wholesalers,” Sammons said. “That’s shifting.”