It’s been three months since a Wisconsin State Trooper seized nearly $10,000 and a small amount of marijuana from Clifford Skinner as he returned from his mother’s funeral in Indiana.

Police never filed criminal charges, but the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration intends to keep the cash on suspicion it’s tied to illegal activity. His case is an example of the burden that falls on those who have cash, vehicles or property seized by police — even five years after Wisconsin passed a law to keep seizures from happening without a criminal conviction.

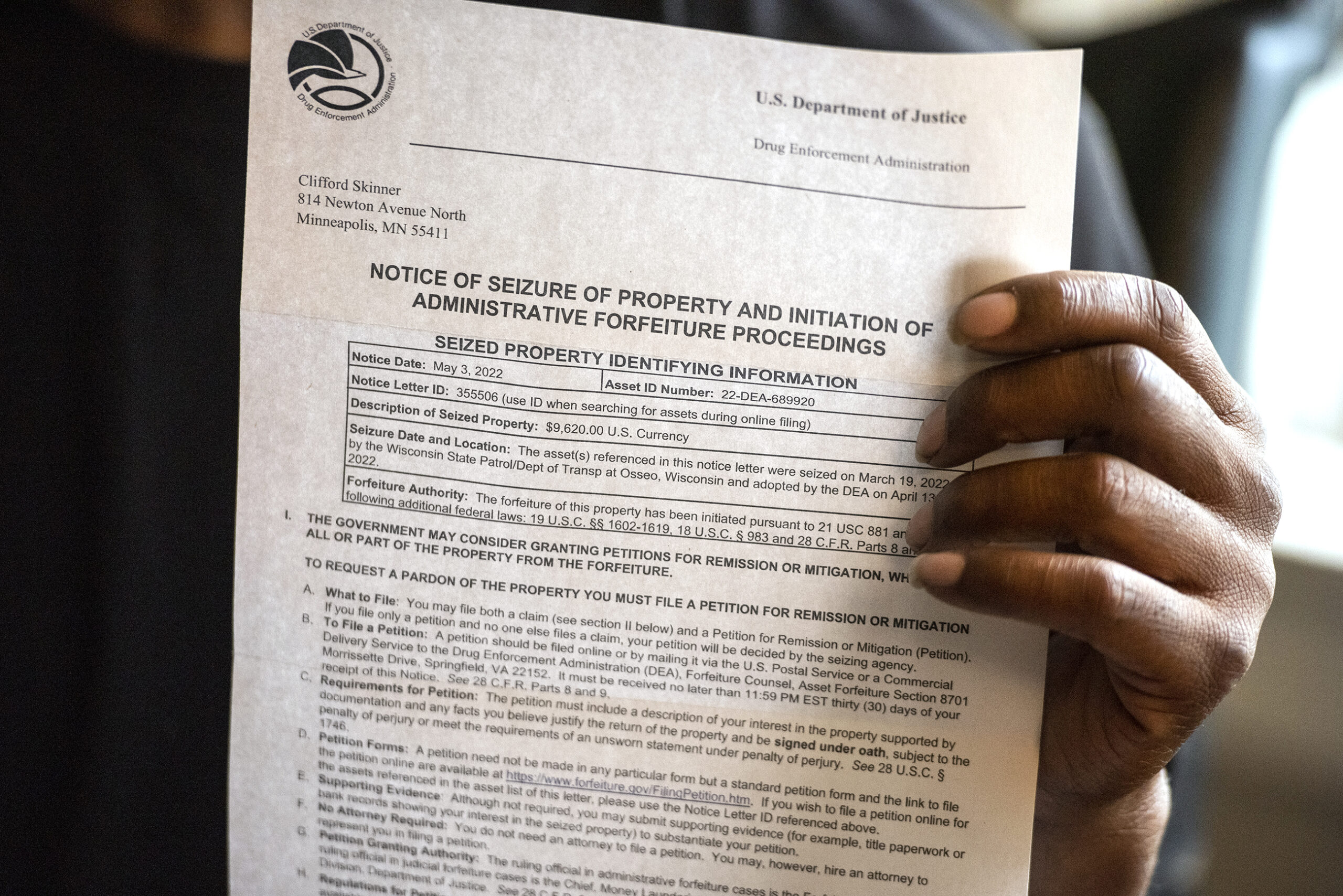

Before driving to his mother’s funeral in Gary, Indiana, on March 19, Skinner gathered more than $9,620 he and his fiance say came from COVID-19 stimulus checks. In an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio, Skinner, who lives in Minneapolis, said the family talked beforehand about pooling money for funeral expenses. Skinner said when he met his father, he was told expenses would be taken care of, and he should keep the money to care for the seven kids of his own.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

On the way back to Minneapolis, Skinner’s daughter was pulled over for speeding by a state trooper on Interstate 94 near Osseo.

The trooper gave his daughter a warning for speeding and turned his attention to Skinner.

“He approached me and said that he smelled marijuana coming from the vehicle,” said Skinner. “I informed the state trooper that I am a medicinal cannabis user and my doctor prescribed me that as medication.”

While marijuana is treated as a medicine for some in Minnesota, it’s considered a schedule 1 narcotic in Wisconsin. Skinner said he gave the trooper less than a quarter ounce and told him about the cash he had in the vehicle.

The trooper seized the money, too. Skinner said he told the officer it came from COVID-19 stimulus checks sent to him and his fiance.

Skinner and his family stood by while the trooper searched the van for more drugs. After finding none, the trooper wrote tickets for possessing marijuana and a grinder and gave him a receipt documenting the seized cash.

After getting home, Skinner and his fiance, Trina Lewis, collected and sent copies of the stimulus checks and marijuana prescription to the State Patrol to show where the cash came from and why he had the pot.

On April 1, Skinner got a letter stating that the Trempealeau County District Attorney’s office wasn’t pursuing criminal charges against him. Instead, he received two municipal citations for the pot and grinder, which are not criminal offenses and do not require a court appearance. Regardless, Skinner plans to fight those as well.

Since he wasn’t charged with a crime, Skinner assumed his money would be returned. During a phone call with a state patrol captain, Skinner said he learned the cash was referred to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration because officers suspected it was tied to drug trafficking.

Skinner said the accusation was humiliating, in part, because he had been convicted of selling drugs in 1998. Court records show no drug related charges since then, other than the Wisconsin marijuana citations.

“When he said that — ‘We are trying to see if this money was drug related’ — it threw me into a (tailspin),” Skinner said. “I kept reflecting back as to, I used to do that. I’m no longer doing that, but I’m still getting accused of doing it, you know?”

Skinner, who is Black, also said he believes the State Patrol’s assumption about his money is due to the color of his skin.

The State Patrol told WPR it doesn’t comment on ongoing investigations.

Lewis said the stimulus funds had given the family some breathing room with bills, and the two were thinking of using the cash toward a down payment on a house.

But Lewis is less worried about the money than she is about the impact the traffic stop near Osseo had on their kids, who she said were put in a squad car while their van was searched.

“My kids, as we see the police driving down the street, taking them to day care, they tense up,” Lewis said. “They get worried. That’s not cool.”

Lawmakers tried to put limits on asset seizures. There are many loopholes.

Despite numerous calls to the State Patrol, Trempealeau County District Attorney’s office and Drug Enforcement Administration offices in Minnesota and Wisconsin, Skinner said he didn’t get a straight answer about where his money had gone or how he might get it back. On May 6, he got a letter from the DEA stating it intended to keep the cash even though he had never been charged with a crime.

The process known as civil asset forfeiture allows law enforcement agencies at the federal level and in some states to keep money, vehicles or property suspected of being tied to criminal activity. The idea is to hamper the drug trade by seizing profits and passing some on to law enforcement to fund ongoing investigations.

But critics of the process claim it is being abused, especially in cases where individuals are never charged with crimes. Those concerns led to a reform of Wisconsin’s forfeiture law in 2018, which was supported by Republican and Democratic legislators and championed by the Wisconsin chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, conservative advocacy groups like the Heartland Institute, Americans For Prosperity and the conservative law firm Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty.

The bipartisan effort was led by Republican State Sen. Dave Craig, who retired from the Legislature in 2020. In a video posted online in 2019, Craig called civil asset forfeiture a “big government policy at its worst.”

“This practice has seen widespread abuse in other states and remains constitutionally suspect here in Wisconsin,” Craig said.

Craig said the reform bill he authored requires a conviction before forfeiture occurs and requires “full due process rights” for individuals.

If Craig’s original bill had passed, Skinner would have likely gotten his money back after the Trempealeau County District Attorney decided against filing criminal charges.

But the legislation was amended at the request of groups like the Badger State Sheriffs’ Association to allow state and local police to request agencies like the DEA “adopt” seized assets and forfeit them under looser federal rules, which don’t require convictions.

Craig did not respond to interview requests for this story.

Retired Madison defense attorney Stephen Meyer spent much of his career representing people whose assets were being forfeited by state and federal law enforcement. He said there are financial benefits for local and state law enforcement agencies sending seized cash, vehicles or other property through the federal process.

“Local law enforcement makes more money by turning it over to the feds,” Meyer said.

If seized assets go through the state forfeiture process, law enforcement agencies can keep up to half of the seized cash or proceeds from vehicle or property sales following a conviction. The other half must be deposited into Wisconsin’s Common School Fund. State law allows assets forfeited at the federal level to be sent back to local law enforcement after a conviction. In those cases, local agencies get 80 percent of proceeds and federal agencies keep the rest and when there is no conviction, local agencies’ portion goes to the school fund. However, there are exceptions. Under Wisconsin law, state and local agencies can keep proceeds from federal forfeitures that don’t result in convictions if an individual has died, been deported, fled the jurisdiction or if the assets are unclaimed for at least 9 months.

State and local law enforcement agencies in Wisconsin reported $774,502.50 in proceeds from forfeitures in 2020, a new requirement under the reformed law. That same year, the U.S. Department of Justice sent more than twice that amount, $1,924,047, from federal forfeitures to state and local law enforcement in Wisconsin who conducted the initial seizures. The process of sending federal forfeiture proceeds back to local agencies is known as equitable sharing.

Brown County Sheriff’s Department Lieutenant Matt Ronk is the director of the Brown County Drug Task Force, which includes 18 officers. In 2020, the Sheriff’s Department received $114,603 from federal forfeitures and the task force reported $83,923 in conviction-related forfeitures to the state Department of Administration. He said payments from federal forfeitures can sometimes take years to get back to the task force.

Ronk said the forfeitures supplement the budgets of the department and task force and is used to pay rent or purchase vehicles used in undercover work. This year, Ronk said he’d like to use some to purchase equipment that can extract information from cell phones.

He said since April, police have made three traffic stops in Brown County where more than $50,000 in cash was seized in each instance.

“(Drug dealers) don’t like to lose drugs,” Ronk said. “They don’t like to lose property. But they really don’t like it if we take money.”

Some members of the Brown County Drug Task Force have been deputized by the DEA, Ronk said, which helps with coordination on complex drug investigations. It also provides an option of pursuing asset forfeitures at the state or federal level.

Ronk said leaving drug proceeds on the street is another way of victimizing those suffering from addiction, and perpetuating the cycle of violence tied to the drug trade. But he understands the concerns about police seizures impacting innocent people.

“I’m an American citizen, too,” Ronk said. “I wouldn’t want my property seized by any government agency. But all my proceeds and all my money is legitimate.”

‘That is contrary to the American system of justice’

The national public interest law firm Institute for Justice has been calling for state and federal reforms to civil asset forfeiture for years.

The lion’s share of federal forfeitures come from joint task forces made up of state and local officers, said Dan Alban, co-director of the National Initiative to End Forfeiture Abuse. These local officers are cross-sworn as federal officers connected to a federal agent from the DEA, FBI or Department of Homeland Security.

“And so it’s a very thin thread that connects what these task forces are doing to the federal government,” Alban said. “And it seems to be a way to deliberately circumvent state law.”

The federal equitable sharing program is especially pernicious, said Alban, because it incentivizes state and local police to bypass state laws by sending forfeitures through federal agencies in order to keep more of the proceeds.

A 2020 study of national and state civil asset forfeiture laws by the Institute titled Policing for Profit found that in 2018, more than $3 billion was forfeited by 42 states, the District of Columbia and the federal government. Of that total, state and local accounted for around 20 percent of cases, according to the report.

Forfeitures can be a vital tool for law enforcement in thwarting criminal activity if they’re accompanied by a conviction, said Alban. The problem is that civil asset forfeitures have been expanded to include those suspected of being involved in a crime — and it falls on individuals to prove their innocence before property is returned.

“That is contrary to the American system of justice,” Alban said. “We do not allow law enforcement to punish people because they suspect that they have committed a crime. We make law enforcement prosecute and convict those people before they’re allowed to be punished.”

A 2017 report on the DEA’s oversight of cash seizures and forfeitures by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General found that the DEA could verify just 44 of a sample of 100 seizures advanced or were related to criminal investigations.

“This means that in over half the cases there was no discernable connection between the seizure and the advancement of law enforcement efforts,” said the OIG report.

In response to a WPR interview request for this story, a spokesperson for the DEA sent links to federal codes governing asset forfeitures and declined to comment.

‘It doesn’t make sense’

Wisconsin is one of 32 states to have reformed civil asset forfeiture laws, but the Institute for Justice claims that without an end to the federal equitable sharing program, forfeiture abuses will continue.

In April 2021, a bipartisan group of U.S. Representatives introduced legislation that would raise the burden of proof required to forfeit property, end equitable sharing, and direct all proceeds to the U.S. Treasury rather than the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Fund. In 14 months, the bill hasn’t been put to a vote.

In the meantime, individuals hoping to keep cash or property from being forfeited by the federal government must either petition the agency that is holding it or file a claim in federal civil court. Attorney’s Alban and Meyer say it’s a complex process and the chances of succeeding without legal representation is slim.

Skinner has hired a lawyer, which means he faces estimated legal fees of $4,000 in hopes of getting any of his $9,620 back.

“I understand nothing is free in this world, and you have to be paid for your services,” Skinner said. “But I think that is basically a slap in the face because our money was legally obtained. And I have to give you $4,000 of my money to get $5,000 back. It doesn’t make sense when I haven’t done anything wrong.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.