For all the millions of dollars being spent on this year’s presidential campaign, for all the thousands of hours of staff and campaign work, for all the TV commercials and digital ads, campaign rallies and letters to the editor, Democrats are not going to win in Taylor County.

They know this. In this rural part of north central Wisconsin, their ambitions are more modest than that.

“If we could get the Democratic vote to 35 percent, it would be huge,” said Jim Davis, co-chair of the Taylor County Democratic Party.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The fact that barely more than one-third of the vote is considered an aspirational goal is a sign of just how far rural areas have swung toward Republicans since the 2010s. But it is also true that in some parts of the state, 35 percent for Democrats would likely mean that presidential nominee Kamala Harris is having an excellent election night.

The GOP wants to maintain or expand its already massive rural advantage in November. Democrats want to nibble away at those margins enough that their base voters in cities and suburbs can carry them to victory.

With about 20,000 residents, Taylor County will represent a small sliver of the state’s total vote, which will likely exceed 3 million in November. But it’s a microcosm of the state’s rural counties in some ways, and it’s one of the reddest in the state.

In 2020, Republican President Donald Trump got nearly 72 percent of the vote there. Democrat Joe Biden, who won Wisconsin, got barely over 25 percent.

Even the 2023 landslide that put liberal Justice Janet Protasiewicz on the state Supreme Court didn’t reach Taylor County. She got 56 percent of the statewide vote but only 30 percent in Taylor County. The last time the county was remotely close for Democrats was in 2008, when Barack Obama lost by a point to Republican John McCain.

“Things shifted pretty rapidly after that,” said John Germain, the other co-chair of the Taylor County Democrats. “Trump really keyed into the rural voters … and not just this county. All rural counties across the country are similar.”

For Germain, Davis and other volunteers, persuading their neighbors to make their preferences known can be a challenge. Some in the area who are politically sympathetic don’t want to put up Democratic yard signs for fear they will be vandalized or stolen. Some local business owners don’t want to publicly support a candidate that a supermajority of their neighbors oppose.

But in the push to the Nov. 5 election, both Democrats and Republicans are searching for every last vote they can find in 50-50 Wisconsin. For Republicans, that largely means targeting nonvoters in rural parts of the state. For Democrats, it means the slow process of rebuilding the rural connections they’ve lost.

In the Republican Northwoods, volunteers reach out to nonvoters

Outside of the Oneida County Republican Party headquarters in Rhinelander, a wooden cutout of a red elephant holds an American flag in its trunk, a Trump-Vance sign taped to both sides. Inside, T-shirts featuring the image of Trump after the July assassination attempt are available for a $20 donation. A hat that says “I’m voting for the felon” will cost you a $25 donation.

On an afternoon in late August, U.S. Rep. Tom Tiffany, a Republican from Minocqua, told a group of Northwoods volunteers that their efforts there matter.

“I feel really good about where we’re at here in Wisconsin,” Tiffany said. “We win Wisconsin, Donald Trump wins the presidency. Simple as that.”

Tiffany said GOP volunteers with his campaign have knocked on some 20,000 doors in the state’s sprawling 7th Congressional District, which encompasses much of northern and western Wisconsin. It’s not a competitive district — Tiffany won both of his last two re-election campaigns by more than 20 points — so some share of these efforts amounts to work on behalf of statewide Republican candidates.

In an interview, Tiffany said the transformation of rural Wisconsin into strong Republican territory started under former Gov. Scott Walker, who first won election in 2010. But Trump, Tiffany said, “put it on overdrive.”

He said rural residents “saw him as speaking to the average person — speaking to those who maybe don’t have a college education. They’ve worked their whole lives. They view (Republicans) as, ‘They’re speaking for us.’”

James Rhody, a 17-year-old high school senior from the Price County town of Spirit (population 292), has been part of Tiffany’s door-knocking effort. Though Rhody personally was drawn to Republican politics out of anti-abortion convictions, he said most of the voters he talks to say they want less immigration and want to see the next administration “lock down” the southern border. They were frustrated over the high inflation the U.S. saw in 2023 and continue to be worried about the cost of living.

As for why Republicans have made such gains in rural areas, Rhody sees the party as “doing the best job of representing the needs of the common, actually working-class citizens at this point” by opposing immigration increases that could drive wages down at the bottom of the income scale.

But politics is never just about issues, and it is apparent in many parts of the state that enthusiasm for Trump specifically has become a part of many people’s rural identity. Across the street from the GOP nominee’s early September campaign rally in Mosinee, a tractor supply store had put up “Make America Great Again” banners. On country roads in central Wisconsin, some houses didn’t have to wait for new flags and yard signs from the 2024 campaign because they simply never took down their displays from 2020.

The Trump campaign said 7,000 people attended the Mosinee event, where GOP leaders urged supporters to vote early, volunteer for the campaign and reach out to persuade people they know to go to the polls.

A Trump campaign official said Republicans are using demographic data to target people who either identify as Republicans or have cultural affinities with conservatives — but who don’t typically vote. In rural areas, that means hunters, regular churchgoers and other groups whose views may correlate with the GOP.

The campaign believes Republicans, even as they’ve lost votes in the suburbs in the Trump era, have the potential to gain even more ground in rural Wisconsin this year.

This may be a challenge, and not only because their vote share is already high. Democrats have ramped up their own rural outreach programs, and this year, unlike in the pandemic year of 2020, they too have armies of volunteers going door to door across the state.

At the same time, at the top levels of the Republicans’ national campaign, recent reports have had some officials expressing concern that Trump’s voter turnout operation is not robust enough to win. The Trump campaign has given over much of this work to outside political action groups rather than the traditional Republican Party structure — a complex system that could make it hard to efficiently coordinate voter targeting and turnout efforts.

And the candidate himself has downplayed the importance of focusing on voter turnout.

“Our primary focus is not to get out the vote, it is to make sure (Democrats) don’t cheat,”Trump said at a North Carolina rally in August. “We have all the votes we’ll need.”

Democrats hope volunteer organizing, VP candidate can make connections

Dave Thompson, 80, is a retired dairy farmer and milk truck driver who lives west of Gilman (population 378). He drives his blue pickup truck in local parades for the Taylor County Democrats. He’s a lifelong Democrat, but he’s gotten more involved in party politics in the Trump era.

“I don’t want to run down anybody, but I don’t want Trump,” Thompson said. “I don’t like the way he talks. I don’t like how he runs people down.”

In a way, Thompson is a throwback to a time when Democrats had stronger support in rural Wisconsin. His parents were Democrats who voted for U.S. Rep. Dave Obey, a Democrat who served in Congress for nearly four decades. A harder question for the party is how to gain the support of rural residents who don’t have those lifelong ties.

In the months since President Joe Biden said he would not seek reelection and Harris became the nominee, Democrats have reported a surge of enthusiasm among volunteers and voters. The campaign has 50 offices in 43 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties — including 32 counties Trump won in 2020. In mid-September, an official, using campaign jargon, boasted of over 1.8 million “phone calls, door knocks and relational outreach to voters across Wisconsin.”

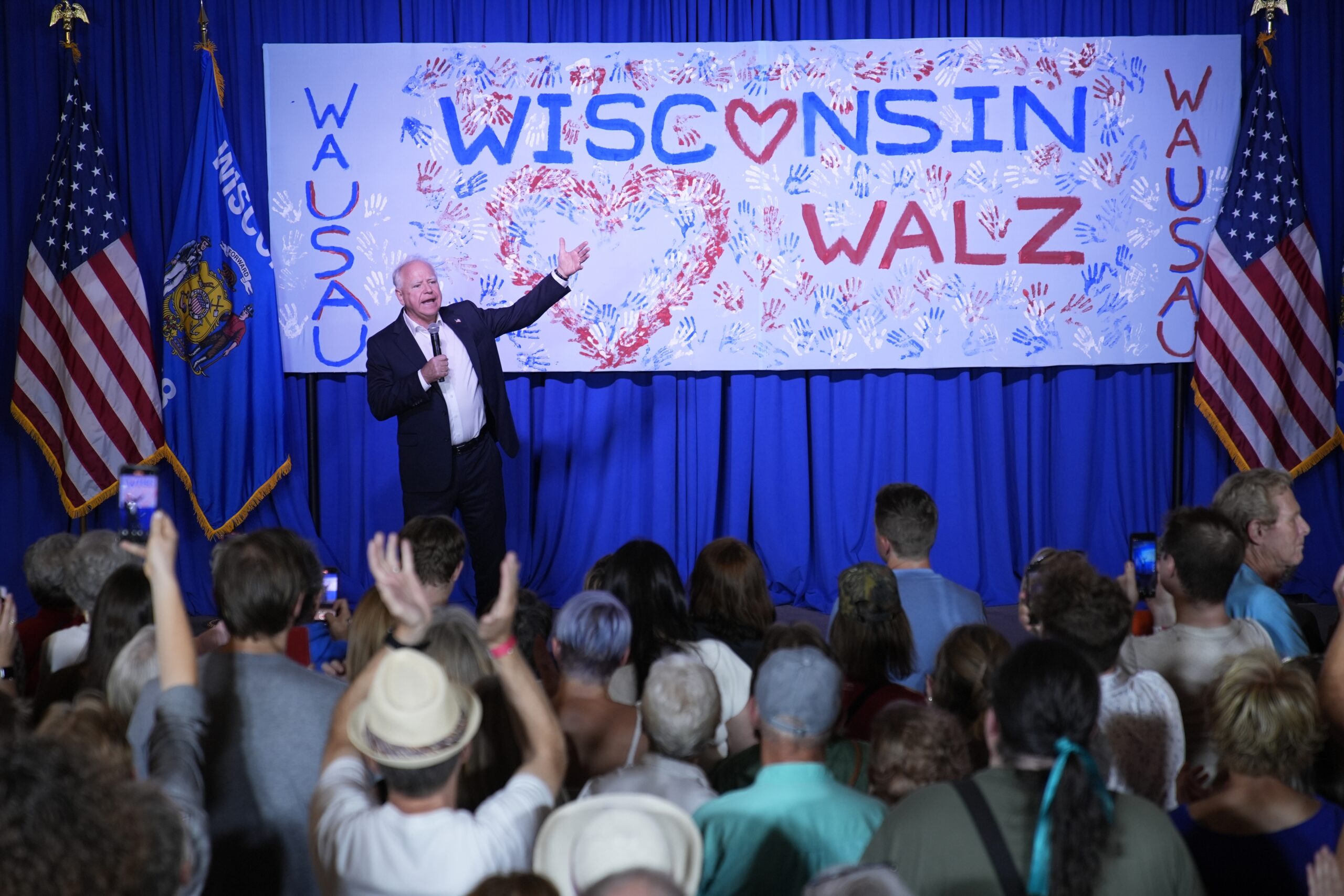

Another component of the Democrats’ rural outreach comes in Harris’s choice of vice presidential nominee. Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz grew up in small-town Nebraska and represented a rural Minnesota district in Congress before becoming governor. He hunts, wears a camouflage cap and talks in his stump speech about his time as a small-town football coach. In affect, at least, he reads as rural in a way many Democratic leaders, including the candidate at the top of the ticket, do not.

Less than a week after Trump’s rally in central Wisconsin, the Harris campaign dispatched Walz to north central and northern Wisconsin for a visit to businesses in downtown Wausau and a campaign rally in Superior.

“What (Walz) brings is an understanding, alongside the vice president, of the need to compete in every single corner of a state like Wisconsin,” said Kevin Munoz, national press secretary for the Harris-Walz campaign. In its outreach efforts, he said, the campaign is “overindexing in a way that Democrats frankly don’t always do in these rural areas. These are voters that, where we can bring down (Republican) margins and increase our vote share, are going to matter in a state that’s going to be as close as Wisconsin.”

Kyle Kilbourn is the Democratic candidate running against Tiffany for Congress. He said the voters he’s heard from care most about access to health care and clean water. And he said the transition from a Biden-Harris to a Harris-Walz ticket has “supercharged” Democratic enthusiasm.

“That excitement and enthusiasm that we haven’t seen since 2008 is getting me very hopeful,” he said.

‘We’d like to see a Harris sign’

Despite all the money and volunteer effort flowing into the campaign, the Harris campaign and the Democratic Party organization are not necessarily reaching all parts of the state.

In September, Germain and other members of the Taylor County Democratic Party met at the public library in Medford, adjacent to a farmers cooperative. They discussed their progress in canvassing their neighbors and wondered when the state Democratic Party would provide them with yard signs. In the meantime, Germain handed out smallish placards reading “KAMALA” that were left over from the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Any campaign organization has to make choices about what to prioritize. Still, it was apparent that Taylor County Democrats felt a little bit left out of the party’s statewide push. They had requested six large signs from the state party to install along highways; they were allotted three. The county party does not have a dedicated campaign office and can’t afford rent for one of its own. Its payout in August from the state party — calculated by a formula based on the number of dues-paying members — was $80.

At the same time, party members said they have had success at canvassing locally. And leaders said they’ve seen a small uptick in membership and donations. They’re hoping once the signs go up, people will see that Democrats do have support in rural areas.

“We’ve been looking at Trump signs for the last eight years or something,” Davis said during the meeting. “We’d like to see a Harris sign out there.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.