Sometimes it’s anyone’s guess what candidates for public office would actually do if they’re elected. But in the race for Wisconsin governor, voters have been given more than 120 examples of what they can expect.

They’re all bills that passed the Republican-dominated state Legislature only to be vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. In the history of the state of Wisconsin, no governor has vetoed more bills in a single session than him.

Evers vetoed bills that would have expanded gun rights, including one that would shield gun makers from lawsuits and another declaring that federal assault weapon bans would not apply in Wisconsin. He vetoed a long list of changes to Wisconsin’s safety net programs, including one that would have cut unemployment benefits by up to 12 weeks. He vetoed bills that would have dramatically reshaped education in Wisconsin, including one that would have let all students, regardless of their family’s income, get state-funded vouchers to attend private school. And he vetoed around 20 plans to change election laws in Wisconsin, many of which would have added hurdles to voting absentee.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Read a summary of all the Republican bills Evers has vetoed here.

During a campaign rally last month in Union Grove, Michels riled up the crowd when he focused on the election proposals and made a promise to Republicans.

“We are going to take those bills — those bills that Tony Evers vetoed,” Michels said. “We’re going to get them right. I’m going to sign them.”

At that same event, Republican Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, Evers’ adversary in the Legislature, went a step further.

“I promise you when we are here in one year with Gov. Michels, every single thing that Gov. Evers has vetoed is going to be considered by the Legislature,” Vos said. “And hopefully all of it becomes law.”

This is one area where Michels and Evers are on the same page. They both say the future of these vetoes hinges on who wins their race.

If Michels wins, these bills can get reintroduced in the next legislative session and Michels can sign them.

And if Michels loses, and Evers is once again governor, those bills probably aren’t going anywhere.

In divided state government, Evers clashed with GOP Legislature

Evers, who was first elected governor in 2018, has served at a time when Republicans held lopsided majorities in the Legislature that could grow even larger next year.

The schism between the two branches of government has been — literally — historic. Evers vetoed 126 bills during the last two-year session of the Legislature, eclipsing the old record of 90 vetoes set in 1927, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau.

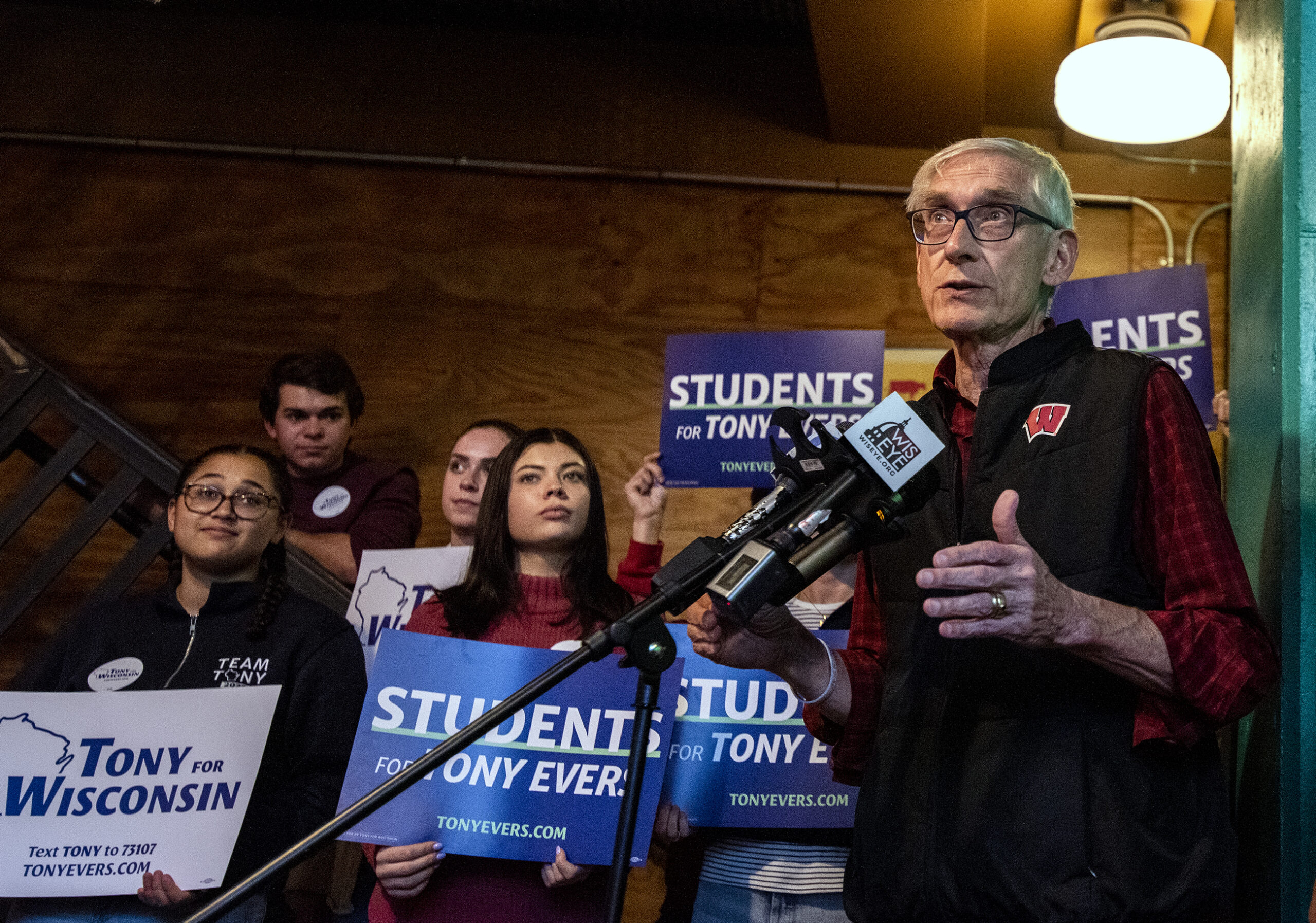

During a September campaign stop at a coffee shop near the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, the college Democrats who came out to support Evers were well aware of his vetoes. Several said they were worried about the dramatic changes that could be in store for state government if Evers were to lose.

“I think in a democracy, you need balancing voices,” said Rianna Mukherjee, a senior at the UW-Madison majoring in political science. “Our Republican Legislature doesn’t balance voices.”

“Without a Democrat as governor … I’m concerned that Republicans will have too much control,” said Elliot Petroff, a sophomore studying political science. “We need to be able to veto things and there’s no other opposition that can do it right now.”

Some students mentioned specific bills Evers vetoed, including some that would have restricted abortions prior to the U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down Roe v. Wade. Grant Hall, a sophomore studying computer science and data science, referenced the election bills.

“I fear that if he is not reelected, voting rights in Wisconsin will take a major hit,” Hall said. “I think those bills would pass pretty easily, and that’s terrifying.”

Evers’ speech to students covered other topics. He told them about what he’s for — supporting higher education, restoring abortion rights and legalizing marijuana.

In an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio after his speech, Evers said voters are well aware of his record stopping bills that most people are against.

“My vetoes reflect my belief system,” Evers said. “I think people understand that part of my job going forward, again, the next four years, will be to be that goalie. And prevent bad legislation from becoming law.”

Saying ‘no’ can have political power

The role of Democratic “goalie” might be expected in divided government, but it’s somewhat at odds with the rest of Evers’ image.

Evers is low-key, a former teacher turned school administrator who won three terms as state superintendent of public instruction by capturing votes from both Democratic and Republican counties. His TV ads promise he’ll “work with anybody.” He promotes the Republican-authored tax cut he signed in the current state budget. He talks about expanding broadband and fixing the roads.

Evers embraces this persona. His repeated clashes with Republican leaders might capture more attention, but the governor said he’s signed far more bills than he’s rejected.

“There are times when people make believe that we don’t agree on anything,” Evers said of his relationship with the Legislature. “But at the end of the day, we actually do accomplish some things.”

Evers signed 267 new laws in the most recent legislative session, for a total of 453 since he became governor. Like countless bills that pass with little fanfare, most sailed through the Legislature with bipartisan support.

But the number of vetoes from Evers has been undeniably high, and precisely who is to blame is debatable. The Republican argument against Evers is that the vetoes show he’s not actually interested in working with the Legislature. The Democratic argument is that Republicans passed far-right bills they knew Evers would veto just to fire up the GOP base and try to paint him as an obstructionist.

Mordecai Lee, a former Democratic state Senator and an emeritus professor at Marquette University, said the vetoes indicate just how bad things have gotten at the Capitol between Evers and the Legislature.

“It’s almost like they live in different worlds,” said Lee. “They don’t talk. They don’t meet. They don’t compromise. They don’t try to work things out.”

And the vetoes only tell part of the story. Evers has also called several special sessions of the Legislature to try to force lawmakers to vote on his issues, like repealing the state’s abortion ban, expanding Medicaid or enacting tougher gun laws. GOP leaders have responded with the bare minimum, gaveling in and out of the sessions without debate.

Evers has also used his powers as governor to introduce budget bills that are packed with policies he wants. Historically, that’s where the Legislature would start its budget deliberations, but Republicans have taken a different approach with Evers, rejecting hundreds of his proposals at a time and building their own budgets from the ground up.

But saying no has its own political appeal. Bill McCoshen, a longtime Republican consultant and lobbyist, worked in former Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson’s administration. Thompson had a reputation for working with both parties as governor, but McCoshen said Thompson earned points with the GOP base for rejecting Democratic ideas.

As governor, Thompson used his partial veto pen to rewrite budgets passed by Democratic majorities. And back when Thompson was the state Assembly’s Republican minority leader, he voted against so many bills that he earned the nickname “Dr. No.”

McCoshen, who supports Michels, said he thinks the same approach could work for Evers.

“It shows the strength of the office and why the office is important,” McCoshen said. “So highlighting that — there’s no downside to that.”

Both McCoshen and Lee said Evers and Michels will emphasize specific vetoes to earn points with their bases. While Michels talks about the election bills, Evers can talk about the abortion restrictions he vetoed before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Even with Wisconsin’s deeply polarized electorate, Lee said there are still pockets of voters who are willing to support either party in any given election.

“And some of them may agree with some of the vetoes and some of them may disagree with the vetoes,” Lee said. “And so for the two candidates running for governor, they’re trying to find those sort of secret hidden voters, and they’re trying to talk to them.”

There is a chance that Republicans wouldn’t pass all of these bills again if Michels becomes governor — that part of the reason they passed so many was that they knew Evers would block them. They got the political upside of passing bills GOP base voters called for with none of the controversy or backlash that could come from actually implementing the policies.

Evers said he doesn’t buy it. He said he’s the only person keeping those bills and others from becoming law.

“I mean, that’s what they promised,” Evers said. “The vast majority of them are gonna come back as quickly as possible. And (Michels) will sign them. Absolutely. That’s a statement of his value system that I think is the reason that people should be voting for me.”

Read a summary of all the Republican bills Evers has vetoed here.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.