In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott case that black people — both enslaved and not — had no rights within United States borders. The ruling took place just four years before the American Civil War.

Fewer than 10 years later, the Union won the war, slavery ended and some began to ask, “What about black people?” Eric Foner, a DeWitt Clinton professor emeritus of history at Columbia University, considers this question in his recently-published book, “The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.”

The results of the conversation about how to address black people’s citizenship upended the original Constitution, he said. It went from a set of rules that sought to protect citizens from the federal government to one that reconfigured its government into a “custodian of freedom,” as the abolitionist and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner once said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

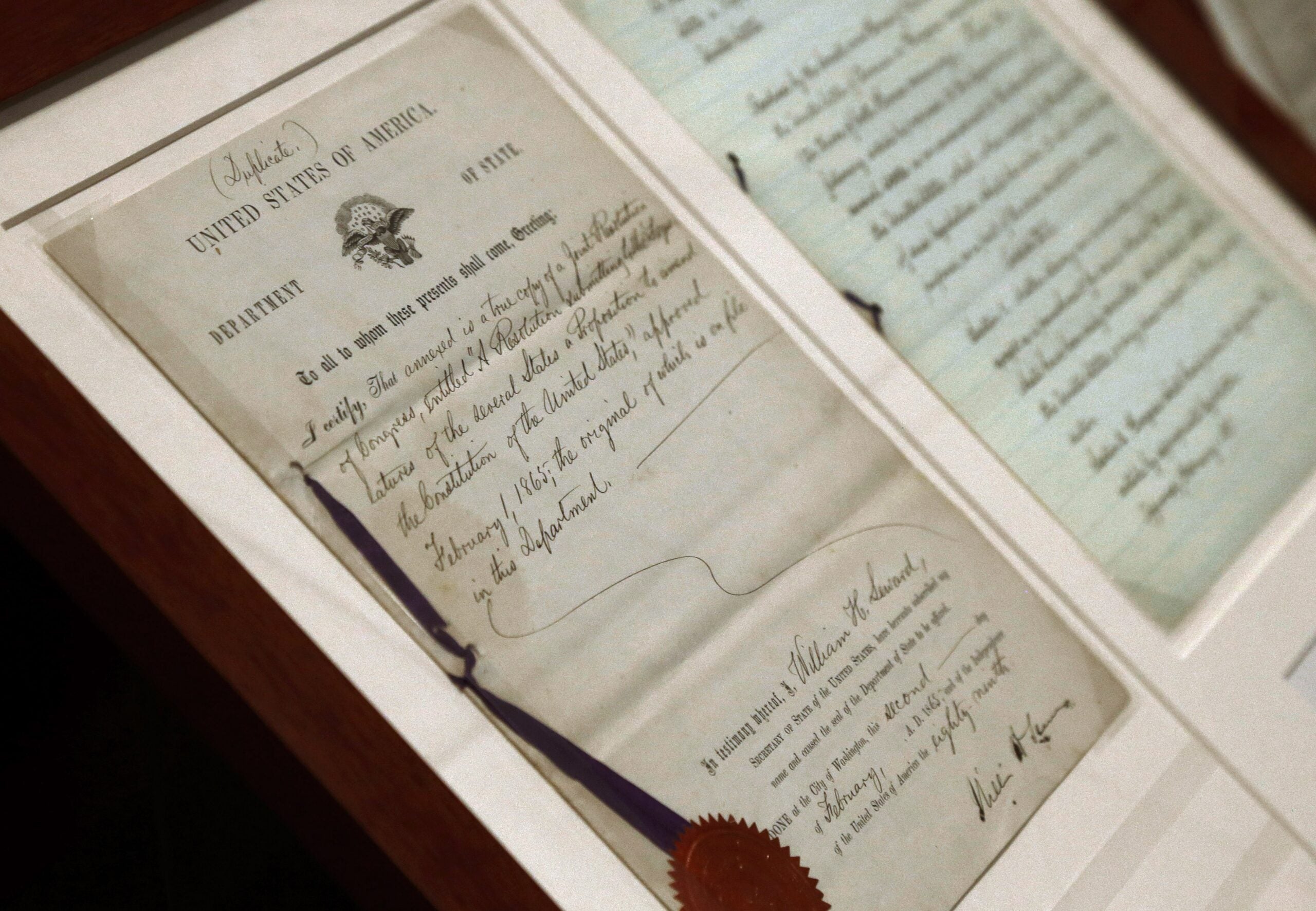

Foner references three amendments in particular that had this effect. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery, which the original Constitution protected. The 14th Amendment defined a U.S. citizen as anyone born in the country regardless of race, religion, national origin, etc. And the 15th Amendment extended the right to vote to black men.

“These amendments really changed the nature of the relationship between individual Americans and the federal government that made the federal government responsible for protecting these rights that were being written into the Constitution,” Foner said.

These amendments set the nation on a new trajectory, one that gave the federal government latitude over determining how new legislation should be enforced, Foner added.

But as Foner points out, the Constitution means what the U.S. Supreme Court says it means. So when the Supreme Court responded lackadaisically to some southern states’ attempts to thwart the new legislation, the amendments began to lose efficacy.

Foner points to the fact that black men’s right to vote was basically done away with in the south around 1900. It wasn’t until 60 years later, during the Civil Rights movement, that the strength of these amendments was resurrected.

“One of the lessons, which is certainly relevant today, is rights can be gained and rights can be taken away, particularly when you have a conservative Supreme Court as they did after the Civil War and into the early 20th century,” he said.

These amendments still have an impact today — including the 2015 use of the 14th Amendment to expand the right to marriage to same-sex couples.

And while the 15th Amendment directs against denying someone the right to vote based on race, other practices — such as literacy tests, “understanding clauses” and “grandfather clauses” — have been used to preclude some American citizens from voting.

That’s still happening in some states, including Wisconsin, where Voter ID laws have been put in place that disproportionately affect minorities, Foner said.

“That’s an astonishing thing — 150 years after the Civil War, and there’s no uniformity between the states,” he said. “Even though we consider ourselves a democracy, the right to vote has always been contested. And there’s always been people who think too many people are voting, and we have to try to get rid of some of them.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.