A new master’s degree program starting this fall at the University of Wisconsin-Madison will prepare students for careers studying the therapeutic effects of psychoactive drugs to treat mental illnesses such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Once legal and a flourishing potential treatment option in the field of psychiatric research, psychedelics were swept up in the counterculture movement of the 1960s, made illegal and lost credibility during the war on drugs.

But reignited interest over the past decade in psychedelics as a legitimate therapy option has led to an increase in the number of clinical trials to test psilocybin (the psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms), MDMA (also called ecstasy and molly) and LSD. Reputable universities, including Johns Hopkins and Berkeley, have established research centers to study the effects of these drugs as therapies.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Completely online, the master’s program at UW-Madison is the first of its kind in the country, said Cody Wenthur, an assistant professor at UW-Madison’s School of Pharmacy. He is the director of the new Psychoactive Pharmaceutical Investigation master’s program.

Wenthur said students’ training will focus on psychedelics, dissociatives, cannabinoids and other psychoactive pharmaceuticals. Anyone interested in applying for the master’s degree program can do so by July 31 for fall admission.

“We’re particularly interested in training students to enter the growth pharmaceutical industry surrounding the use of these substances, providing them with the tools to understand the data and also to work in an ethical manner and adhere to all the regulatory pieces surrounding the use of these compounds,” he said.

Some states have decriminalized the use of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes, but Wisconsin isn’t one of them. Wenthur said he and his colleagues are required by law to have Schedule 1 licenses to work with these compounds. Schedule 1 means these drugs have no medical accepted use according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

But it’s complicated, Wenthur said, because both MDMA and psilocybin have been termed as potential breakthrough therapies by the Federal Drug Administration in treating PTSD and depression, respectively.

Wenthur said some of the psychedelics he uses in his lab come from the Usona Institute in Madison, a nonprofit focused on studying the effects of these drug therapies and supports the manufacturing of pharmaceutical-grade psilocybin.

Research is still underway to determine the impacts of these drugs on mental health disorders. MDMA is in the last stage of clinical trials for PTSD treatment, and psilocybin is in the penultimate stage for treatment of depression. Early clinical trial research is showing promising results for treatment of substance use disorders and anxiety, particularly for people with a terminal diagnosis.

“Some of the earlier human trials were actually in patients with terminal cancer diagnoses and use of these compounds, with psilocybin in particular, with a single dose or two doses combined with psychotherapy, showed huge improvements in those patients’ anxiety and quality of life,” Wenthur said.

While reports have surfaced of people using psychoactive drugs to treat depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses on their own — including about 6 percent of 110,000 respondents in a Global Drug Survey — doctors warn that these drugs should be taken with caution and trained monitoring.

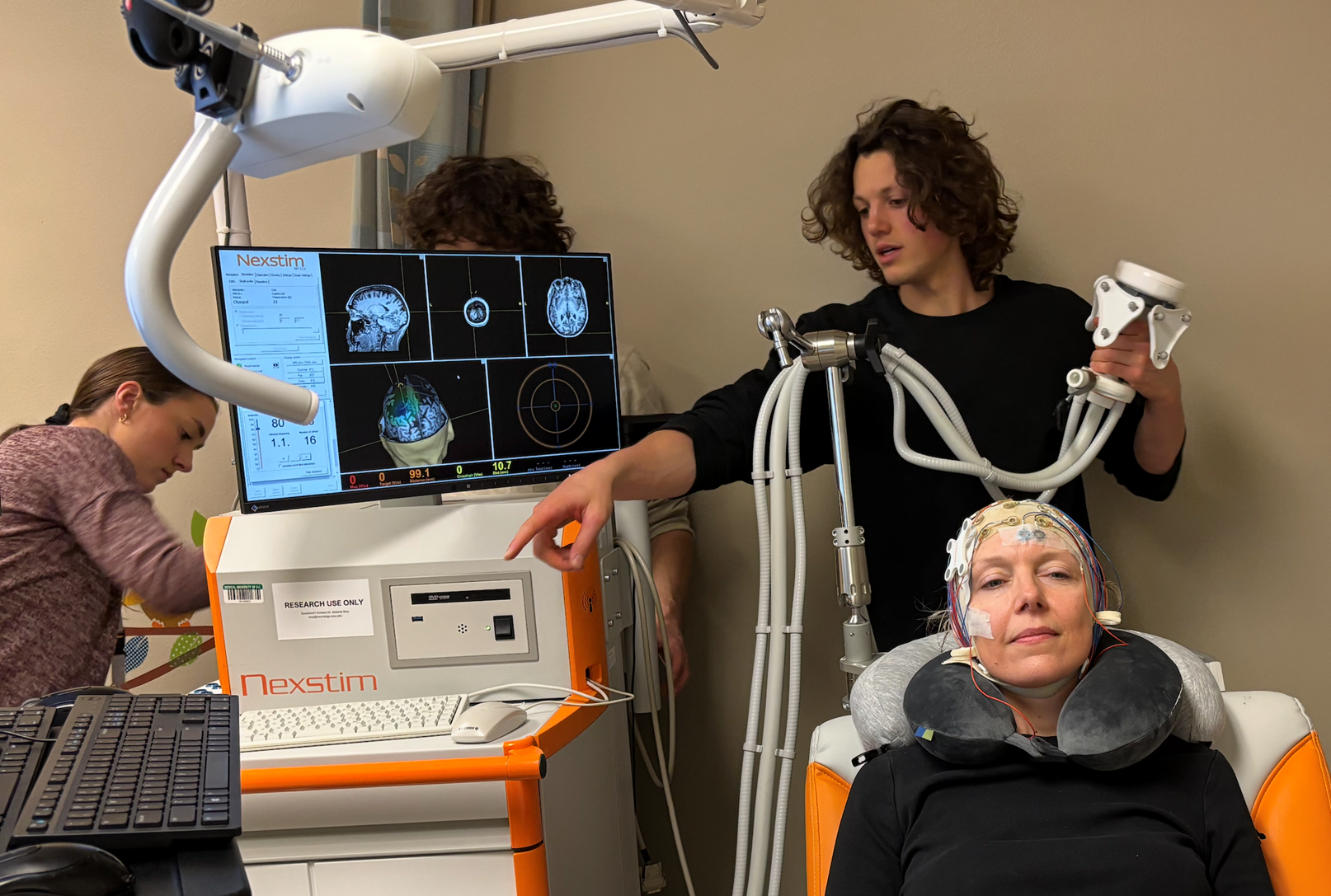

That’s precisely how these drugs would be administered, Wenthur explained. Patients take these drugs within a safe environment and under the guidance of trained therapists who help the patients through the entire experience, including integration sessions afterward where patients and therapists talk about the experience.

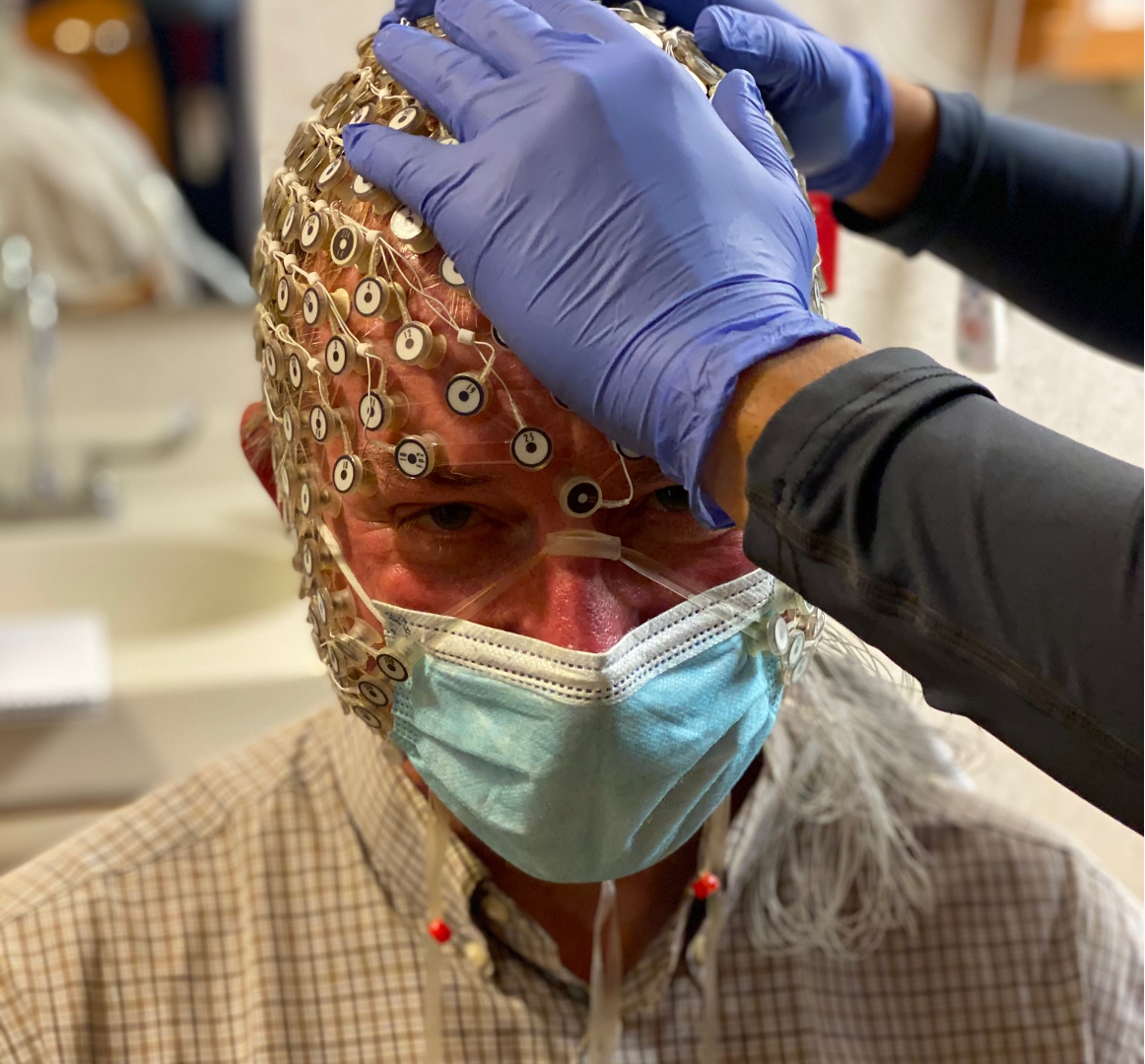

Researchers aren’t exactly clear on what makes these psychedelic drugs work as a treatment, but they suspect it’s related to the way these compounds change how the brain regions connect to and communicate with one another.

There’s also evidence the compounds change the structures of neurons and the ways those cells communicate with each other, which impacts learning and growth.

“The most important first step is for us to not get caught up in the hype and say this is absolutely a 100 percent guaranteed cure for all of societal ills,” Wenthur said. “I think that’s a mistake. But I also think it’s a mistake to ignore the promise that these compounds are exhibiting.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.