Isolated in the middle of the Panama Canal, Barro Colorado Island is cloaked with thick, lush tropical rainforest — home to iconic species like three-toed sloths, toucans and howler monkeys.

With tall canopy trees overhead and dense tangles of plants below, it can be easy to get turned around on this Central American land mass almost a quarter of the size of Manhattan.

As a small group of five people consult compasses draped around their necks to keep them on track, Blas Antimo Perez captures the sentiment in a Spanish phrase.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Las mejores aventuras pasan cuando estás perdida,” he says, or “the best adventures happen when you’re lost.” But they’re not off course for long.

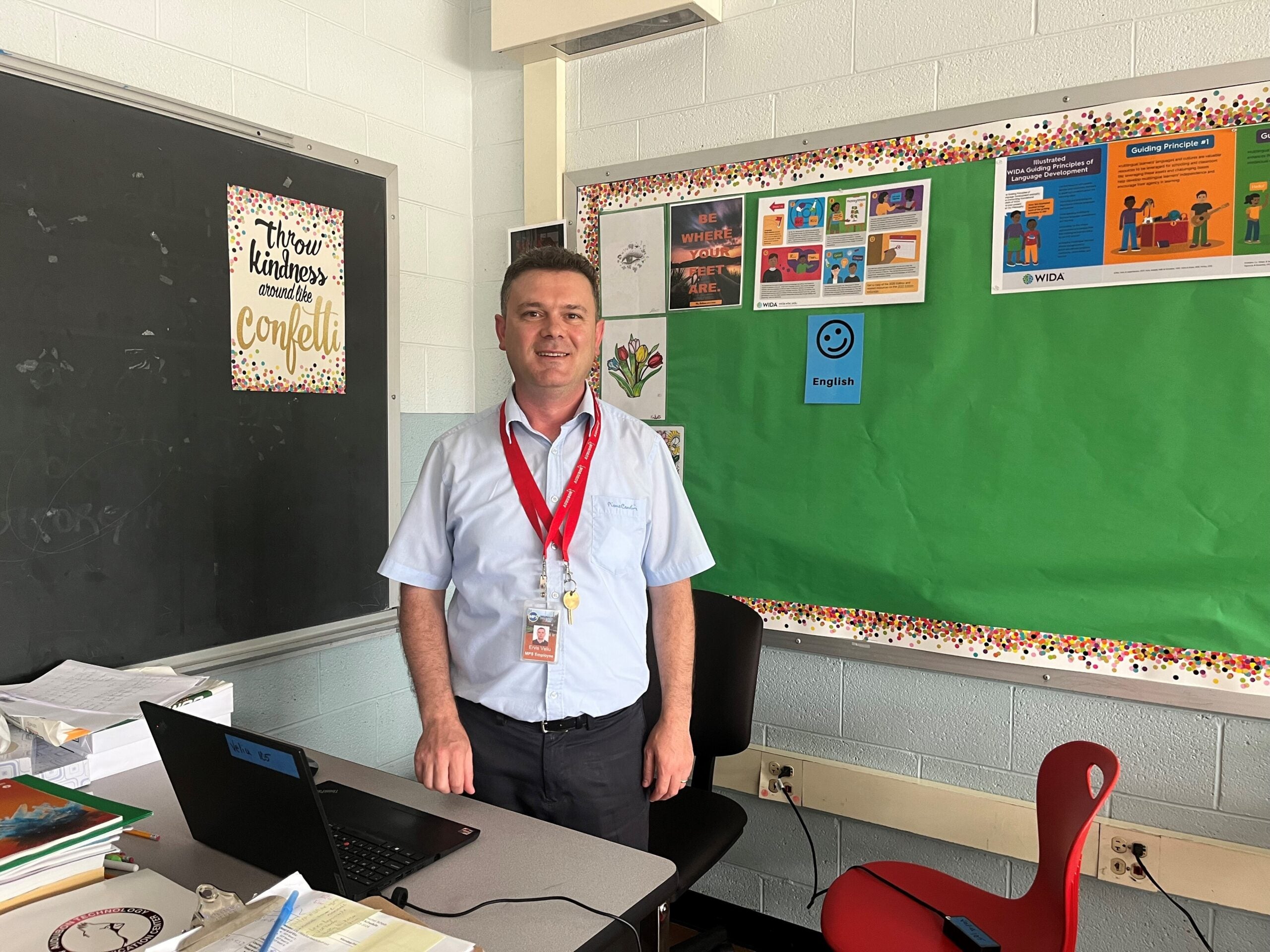

Antimo Perez is a bilingual third-grade teacher in Milwaukee Public Schools, but for the moment he’s a researcher of sorts. He’s helping some field assistants update a census of a plot of land by recording and measuring the location of specific trees and woody vines. This data collection is part of a program designed to expose Milwaukee educators like him to aspects of the scientific method and topics in environmental science.

The ultimate goal is for teachers to then use the experience to inspire lessons back in their Milwaukee classrooms.

“If teachers understand how science is done, and are excited about science, then they’ll be better teachers, and everyone benefits,” said Stefan Schnitzer, a biology professor at Marquette University, who started the project, known as the Panama Experience, for teachers in 2010 with funding from the National Science Foundation.

For a couple of weeks each summer, a small group of Milwaukee instructors embed with members of Schnitzer’s lab, who study things like why different plant species co-exist or grow in certain locations. The teachers get their hands dirty in the field, helping with a research project like the census.

Antimo Perez is already thinking about how he can model a curiosity in the subject for his students.

“It will help them be like, okay, a scientist can actually go out and roll around in the mud, or jump through vines and trees, and that’s also science,” he said.

More than understanding the specifics of his research, Schnitzer said it’s important to immerse the teachers in the rainforest ecosystem. It gives them access to content to create activities and teaching material on concepts such as biodiversity or climate change.

“The tropics basically serve as a hook to catch the attention of the students, to get the students to stop and listen, and say, ‘Wow, you saw that? Tell me about that,’” said Schnitzer, who has been coming to the tropics for almost three decades.

The length of the trip varies year to year but typically lasts three to four weeks, and takes place, in part, on Barro Colorado Island. The location is a hub for scientific activity run by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, allowing the teachers a chance to chat with visiting scientists from a variety of backgrounds.

The teachers receive a stipend for participating in the program, and they share the specialty curriculum they create online so anyone can use it.

In the past, they’ve developed units ranging from weather patterns to geological formations, said Sarah Oszuscik, a longtime Milwaukee teacher who runs the Panama program with Schnitzer. One teacher, Oszuscik said, even incorporated the material into art class, having students make clay necklaces to demonstrate how a common tropical vine called a liana functions.

Traveling to another country pushes many teachers outside their comfort zones, Oszuscik said. It can also remind them of what it’s like to be a student — challenging them to make mistakes and synthesize unfamiliar topics.

“That’s actually what teachers ask of our students all the time … read all this new information, and then tell me what you’re going to do with all that new information,” she said.

Elsi Mercado, a bilingual third-grade teacher who joined this year’s Panama crew, is brainstorming ways to enrich her classroom curriculum with new insight. She’s considering a lesson about animal adaptations that includes how different rainforest birds’ beaks relate to the foods they eat.

She’s also excited to tell her students that her days spent sweating in the field have helped ease her own fear of creepy crawlers. It might help change some of their minds too.

“My teacher faced her fears of bugs,” she hopes they’ll say. “If she can do it, I can do it too.”

When Antimo Perez returns to the classroom this fall, he also plans to incorporate the photos and recordings he’s gathered of tropical creatures like monkeys and crocodiles into units on plants and animals.

Mostly, though, he wants to instill in his young students that anyone can do science.

“Getting them away from the idea that science is you’re in a lab with a lab coat, with a syringe and a beaker,” he said. “It’s just picking up and observing.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.