Forget about the talon-tapping, serpent-tongued and snarling velociraptor that relies on its pack to take down giants like the Tyrannosaurus-rex. Those stars of the 1993 film “Jurassic Park” have little room to boast outside of Hollywood’s roster of most terrifying killers.

For one, archeological evidence shows that velociraptors were in fact just a little bit larger than turkeys. The film’s predators more closely resembled deinonychus, with swiveling front claws and backward-curved teeth.

But deinonychus and velociraptor — both in the raptor family — probably didn’t hunt in packs like the movie suggested, and they weren’t likely to take down prey that was larger than them, according to Joseph Frederickson, a vertebrate paleontologist and director of the Weis Earth Science Museum at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh at Fox Cities.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Frederickson was part of a study published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, that looked at the teeth from deinonychus remains to determine whether these raptors hunted in packs, based on chemistry makeup in the teeth of babies compared to adults.

Frederickson said scientists were beginning to question whether raptors were in fact pack hunters because their distant living relatives — crocodiles and birds — aren’t.

Pack hunters like lions and wolves tend to eat the same food, whether they’re babies or adults, so the scientists who were part of this study hypothesized that if these baby and adult raptors had different diets, then they likely weren’t pack hunters.

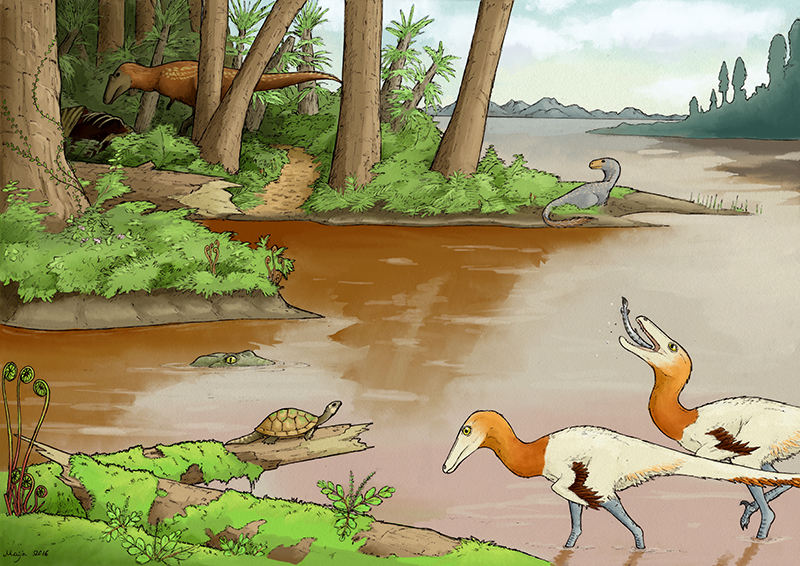

Asocial animals such as crocodiles do not share similar diets with their young. After the babies hatch, they’re on their own for food.

“The mom may hang around for a little while to protect them, but she’s not feeding them,” Frederickson said. Those babies then nibble on minnows, tadpoles and spiders, while the adults eat mammals.

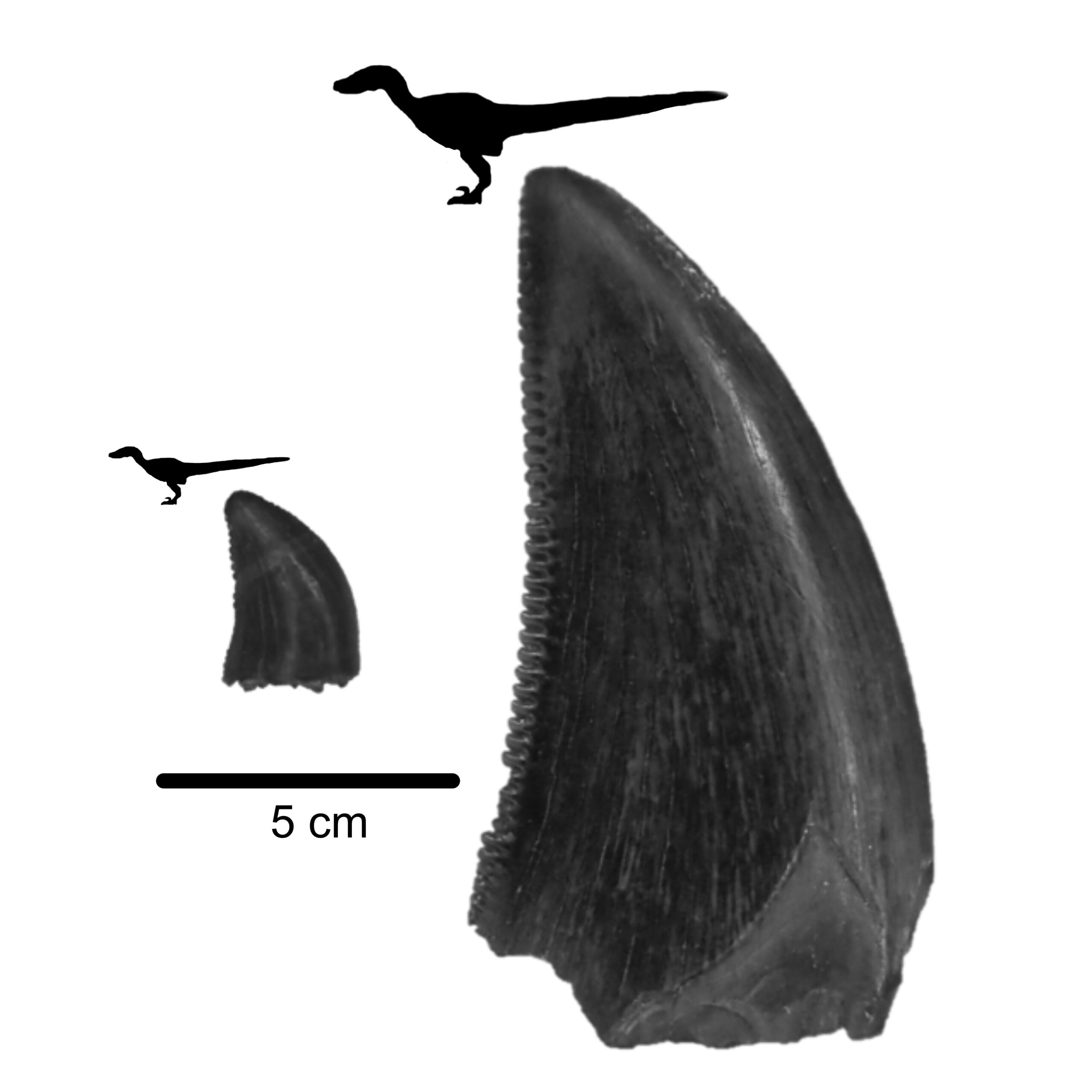

Archeological research into the teeth of deinonychus in sites in Oklahoma and Montana show that the babies had different diets than their parents, measured by testing carbon isotopes in small and large teeth. Babies were eating smaller lizards or mammals and adults were eating big herbivores.

Frederickson said additional research needs to be done to understand if this lifestyle is true of velociraptors, too, because this study only focused on deinonychus, from the Early Cretaceous Period, about 120 million to 110 million years ago. There’s about 40 million years separating deinonychus from the velociraptors of the Late Cretacous Period (74 million to 70 million years ago).

The belief that raptors hunted in packs was popularized by Yale University paleontologist John Ostrom and hinged on multiple skeletal remains of these dinosaurs being found in one location, or bone bed.

Frederickson said more research might help unveil why the bones were found together but noted there are other explanations apart from them being pack hunters. One hypothesis is that while hunting separately, these predators attacked the same prey — just not in any coordinated way.

He said this same behavior is seen in crocodiles, where one will hold onto the prey while another crocodile rips off a piece.

“When we’re talking about pack hunting, we’re talking about a spectrum of behaviors,” Frederickson said. “It is quite possible that deinonychus did work together — it just wasn’t to the same degree as what we would see in a killer whale or a wolf where individuals have their own roles.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.